Love paves the path for a strong dog-human bond

Study

Debottam Bhattacharjee

A recent study from the Dog Lab, IISER Kolkata challenges the notion that dogs associate themselves with humans solely for seeking food. It shows that affectionate behaviour paves the way for dog-human bonding.

Tweet

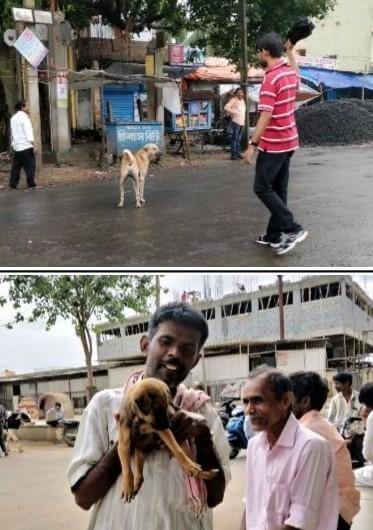

The public perception of street dogs in India seems to be divided. While some have a very humanistic approach towards these creatures, a recent nationwide survey that I conducted suggested that 50% of the people interviewed, considered them to be a menace on the street. While the allegations against “man's best friend” may seem justified, no one till date has tried to judge it through a scientific lens.

In a Developing country like ours, street dogs are an integral part of the society. They are found everywhere, from remote villages to busy metropolitans. They have evolved as scavengers, generally depending on human left-over food, but are also found to be ‘begging’ from people by short or prolonged gazing, while standing or sitting in close proximity. A recent study by VonHoldt et al. (2017) published in Science establishes these activities as dogs’ display of extremely ‘social’ behaviour. Unfortunately, this begging behaviour , so far, has only been linked to their need for food and researchers seem to have overlooked affection and love as the drivers behind it.

Several studies have concluded that pet dogs are remarkably great at communicating with humans. For example, they can follow human pointing gestures or cues to locate hidden food rewards. My studies on the street dogs in India revealed that they are no different, but the most striking discovery was their flexible nature of this particular behaviour.

In a recent experiment, I provided the dogs with two covered opaque plastic bowls, one of which had a food reward inside and tested their responsiveness in multiple trials by pointing randomly at one of the bowls. Puppies ranging from four to eight weeks of age were very fast at approaching the bowls and following pointing cues. Juveniles (ranging from 13 — 18 weeks of age) showed hesitation to approach less of them followed the pointing cue, as compared to puppies. Interestingly, in the case of adult dogs (> 1 year old), after they obtained the hidden food reward, the chances of following my cue again in the next trial increased. But when a dog followed my cue and did not obtain the food reward, the chances of following the cue in the next trial decreased.

My study concluded that such behaviour might have been generated due to dogs' regular interactions and extent of socialization with humans. Puppies at their young age remain mostly protected by their mothers, and have very low exposure to human socialization. Also, people find dog puppies adorable, thus making most of their interactions highly positive ones. When these puppies grow up and become juveniles, they tend to forage in and around human habitations and start to receive negative human impacts like harassment, chasing and beating. So, they become hesitant in terms of approaching an unfamiliar human being. By the time they are adults they have gathered ample life experience on how to approach and respond to a human stranger. Needless to say, they learn to respond differently and in a situation-specific manner, taking into account the previous encounters with human beings.

In order to understand the current status of dog — human relationship in India, my supervisor, Anindita Bhadra of the Dog Lab, Indian Institute of Science Education and Research - Kolkata (IISER- K) and I conceptualized and designed another study. We tested a large number of Indian street dogs to see whether they would choose to pick a food reward from an unfamiliar human hand or from the ground . The idea was to investigate dogs' intentions to make direct physical contact with strangers.

We found that 63% (majority) of the dogs avoided making direct physical contact with the unfamiliar human experimenter and chose ground as the preferred place. Since it was impossible for us to quantify the magnitude of positive and negative interactions these dogs have had with humans previously, we went on to test two subsets of this population in short and long-term conditions.

In canine scientific literature, social contact or petting is considered as a reward which is comparable in importance to food. We re-checked some of the dogs' preferences immediately after providing them with positive social contact, which was defined by petting three times on their heads. We found very little influence as they did not change the preference of obtaining food from ground to human hand. Only the approach time shortened, suggesting a faster response to the short-term social rewarding. In the long-term condition, we checked for the effects of social petting. An additional food reward was provided respectively to two different groups of dogs from a separate subset on specific day intervals from Day 0 to Day 15.

What we found was very surprising — dogs showed less willingness to socialise with the human experimenter even when they received an additional piece of food reward, while provision of a social reward like petting, resulted in dogs' higher exhibition of socialisation with the human experimenter.

Dogs that received social petting became more friendly compared to the group which received an additional piece of food every time. Thus we concluded that dogs rely on affection from humans rather than food for building trust.

Indian streets abound in dog — human conflicts. Previous investigations identified great slack in the dog population management and lack of awareness among people about the dos and don'ts of treating animals as the underlying reasons for such conflicts. Our findings suggest that a more loving approach by humans could reduce these conflicts to a great extent.

So, next time you see a dog on the streets, try being a little compassionate rather than hitting it or shooing it away because affection seems to have a greater impact than food in their lives. What’s better than becoming best friends again?

Dr. Debottam Bhattacharjee has recently completed his PhD from IISER Kolkata. He will be joining Utrecht University as a Marie Curie Fellow for his postdoctoral studies. His research interests range from behavioural ecology to comparative cognition.

signup with your email to get the latest articles instantly