Why Therapies Fail: Prof. Ofer Reizes on Cancer, Collaboration, and Curiosity

SS: Hello Sir, this is Swarnendu Saha from Team Insight. I’m a student here, and it’s an honor for me to welcome you to this interview session. Likewise, it’s an honor for me to have the opportunity to interview you. Okay, so my very first question, which I generally like to start with, is: how did you reach here—meaning the position you are currently in? Could you briefly share your academic and research journey, starting from your school days up to today?

OR: Can I do this in reverse? I’ll start with where I am today and then walk you back to where I started, and why I became interested in science—not necessarily biomedical science.

I am currently a staff professor at the Cleveland Clinic Research Institute, which is part of the larger Cleveland Clinic, an international hospital system that has research as one of its main pillars. We are interested in studying and researching diseases. I joined the Cleveland Clinic almost 19 years ago with the goal of understanding the biology of diseases—essentially investigating what causes them.

The position I hold today, and the things I study now, are not necessarily the same as when I first joined the Cleveland Clinic. Before being recruited there, I actually worked in industry. I was at Procter & Gamble when they still had a pharmaceutical division. That company was focused on obesity and metabolic diseases. From that experience, I learned the process of what it takes to develop a drug and even gained insights into drug commercialization—knowledge that I later carried into my research at the Cleveland Clinic, where I now also teach courses on these topics.

In particular, I teach courses designed to help students understand what kinds of projects industry and commercial enterprises are likely to support, with a focus on whether the product being developed is truly necessary.

That brings us to around 2001. Going backwards from there, I completed my postdoctoral work at Harvard Medical School and Boston Children’s Hospital. That period was really a time of free exploration, which allowed me to focus deeply on the type of scientific questions our lab was interested in. Specifically, this involved studies on obesity, including mouse model research. It was during this time in Boston that I really became more of an expert, as I gained clarity on the importance of defining and narrowing scientific problems.

Before that was graduate school. I pursued my PhD at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, which is still one of the premier health science centers in the U.S. There, I did my dissertation in molecular pharmacology. The work focused first on how to frame a meaningful research question, and second, on how to systematically address it.

Going back another step, that takes us to my college years at the University of Maryland. At the time, I initially intended to go to medical school—that was my main interest. But along the way, I caught the “research bug.” I had the opportunity to work in labs both at the University of Maryland and at the National Institutes of Health as an undergraduate. That experience really switched on a light for me, and I realized I wanted to pursue research as my career.

I won’t go further back into high school.

SS: So, at the University of Maryland, it was College Park?

OR: It was mostly College Park, although I also spent part of my time in Baltimore. The University of Maryland in Baltimore is designated an honors university. I moved there later in my college years because I wanted to study at a university that was well-known and heavily supported by the state, which had invested a lot of money to make it an elite institution.

It was a much smaller campus compared to College Park. College Park tends to be one of the largest schools in the country, probably among the top 10 in terms of size. Baltimore, on the other hand, was much smaller.

One of the reasons I transferred there was a program that offered both a bachelor’s and a master’s degree. It was called Applied Molecular Biology. While not directly related to your broader question, it’s relevant in the sense that the program provided strong technical training, though not much intellectual focus on developing into an independent investigator. I initially intended to spend an extra year there and complete a master’s degree. But while I was there, I realized that wasn’t what I wanted.

I decided, “You know what, this isn’t going to get me where I want to be.” So I finished my bachelor’s degree as quickly as possible and went on to graduate school in Texas.

SS: Okay, I had the chance to visit the University of Maryland, College Park, for a day. I was in Washington D.C. this last December for the AGU conference.

OR: It’s a beautiful campus.

SS: Yes, it was a beautiful campus. I went inside the student activity center and the football stadium. Nowadays, tram tracks are even being built across the campus.

OR: It was different when I went there, though.

SS: That didn’t happen 30 years back.

OR: Was it 30? Yeah, I guess it was. Time flies when you’re having fun.

SS: Yes. So, would you please briefly describe your research area and your research interests?

OR: The best way to describe my current research is that it focuses on cancer—specifically women’s cancers—with an emphasis on understanding why our current therapies fail. In cases of breast, ovarian, or even uterine cancer, patients undergo surgery, but unfortunately the therapies they receive often stop working. The cancer cells become resistant to chemotherapy.

There are many scientists investigating different mechanisms behind this, and we are among them. That’s also something I’ll be talking about here. The central idea is: can we understand why patients fail chemotherapy?

SS: You are not a physician.

OR: I’m not.

SS: So, you are dealing with human cancers—specifically cancers in women. How does a physician’s approach differ in treating it? Because while doing research in this area, you also need regular checkups and datasets to check whether your methodology is working or not. And since you mostly do lab work, data analysis, and theory based on past studies, how do the perspectives of a physician—someone with a medical background—and a scientist like you, from a research background, compare? Are they the same or different?

OR: Okay, that’s an excellent question. My response is that we work as a team—and that’s one of the advantages of being at the institution where I am, the Cleveland Clinic.

The majority of what the clinic does is treat patients, and we also have a very large cancer institute that focuses specifically on cancer patients. My work is closely connected to our clinical group. I collaborate with clinicians at various levels.

SS: By clinicians, you mean doctors?

OR: Yes, yes. So think of surgeons and think of medical oncologists—and I’m differentiating between them.

In some cancer fields, the same physician may do both surgery and treatment. In others, you have a surgeon and a separate medical oncologist. The oncologists are the ones who prescribe the drugs and monitor how the patient is doing.

Now, where do I fit into this continuum—which I sense is really the heart of your question? I fit in at the very beginning: the stage of trying to identify solutions that could eventually be implemented in the clinic. But the important point is, I don’t do this in a vacuum.

A big part of my work involves discussions with my clinical colleagues to understand from them: what is the real problem? Why do patients still die? To put it bluntly, patients get diagnosed with cancer. Some do well, but others pass away very quickly. So the question we try to answer is: what is it that clinicians are unable to treat?

That’s also why I love being where I am. At the Cleveland Clinic, I can have direct conversations with clinicians about their challenges. If I were at an institution without those connections, I could only rely on the literature—which is valuable, of course—but I’d miss the complexity of what actually happens when a patient walks in, gets diagnosed, receives treatment, and then fails that treatment.

Because I have that access, I can talk with clinicians and identify where in the patient journey we should ask questions, where we might intervene, and how we could improve outcomes.

Of course, there are other steps too—like translating discoveries into drugs and clinical trials. We’re at the very early stages: understanding what goes wrong in treatment, developing therapeutics and strategies, and then passing those along to colleagues who can test safety and efficacy in clinical studies. We can do everything up until the point where it goes into a patient—but once it reaches that stage, you need a very different skill set.

SS: So, while doing this work, what kinds of scientific challenges do you face—the cons, the setbacks, the problems?

OR: That’s a great question. One of the main issues is that biology is complex—it always finds a way around us.

For example, we may have a very specific direction and show that, in a particular cancer with certain characteristics, our drug works. But then, there are other cancer types that don’t fit that pathway. They find ways to bypass the mechanism we’re targeting. The frustration is that you end up with a very narrow solution.

Ideally, we want to disrupt the disease process at multiple levels, but in practice, our expertise may become focused on one very specific direction that doesn’t apply universally.

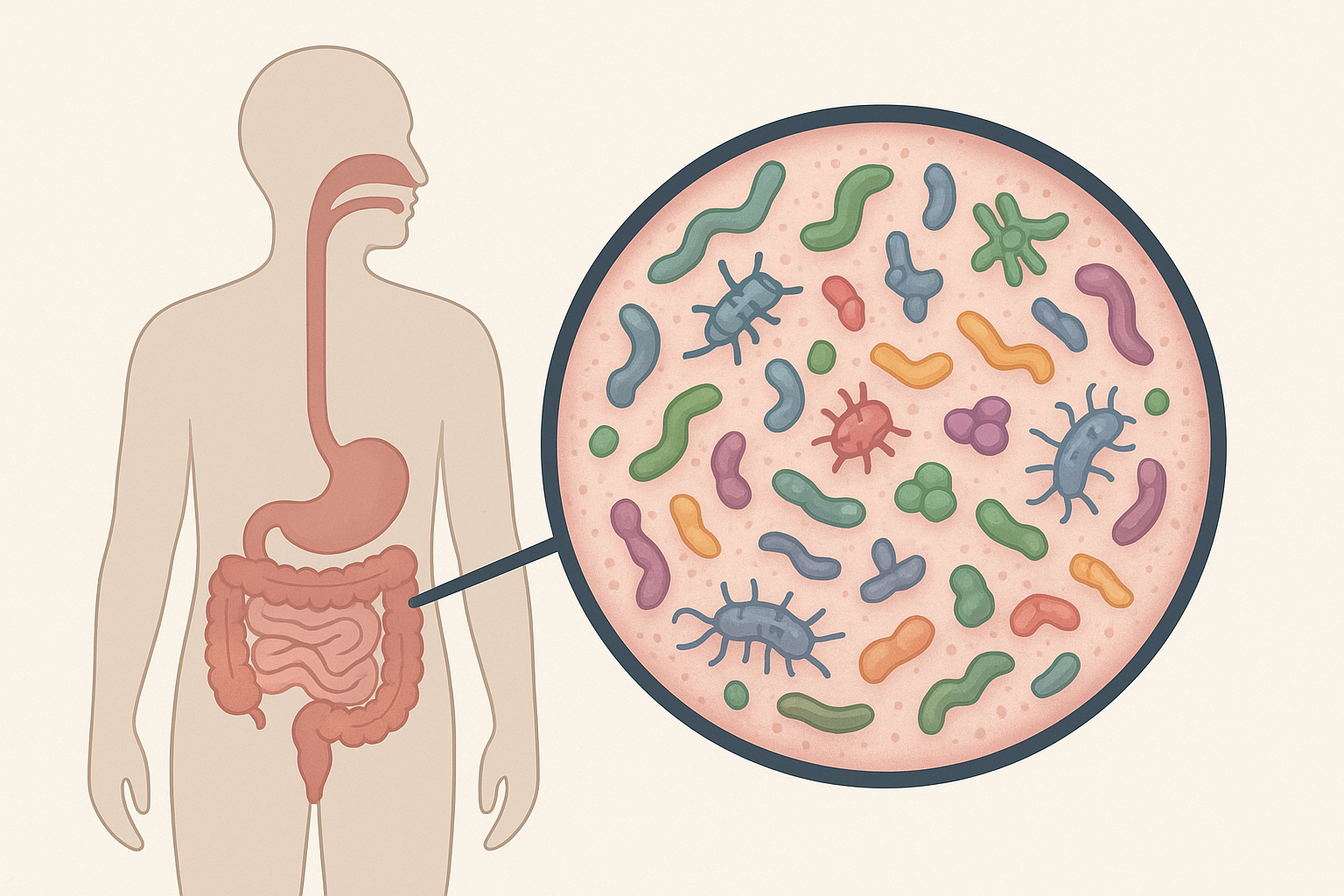

Let me give you an example. One of our projects, which I’m not talking about today, involves the gut microbiome. We know the microbiome is critical for health and disease. The bacteria in our gut digest food but also release chemicals that enter the body.

Several years ago, we did studies with ovarian cancer cells and found that a beneficial factor released by the gut microbiome actually inhibited ovarian cancer growth. We thought, “Fantastic! If we understand this, and also how antibiotics disrupt those bacteria, this could be a real therapeutic strategy.”

But when we tested the same approach in a different subtype of ovarian cancer, it didn’t work.

And that’s the frustration: there is no single solution for every type of cancer. The disease will always find ways to evade treatment.

SS: Do history and geography play a role in this? How?

OR: Well, following up on what I just mentioned, geography has a major impact on the microbiome. The microbiome you have and the one I have are very different. So, patients here would probably respond differently to treatments, depending on how their microbiome interacts with the disease.

The microbiome I’m talking about is in our gut—it sits in our intestines and is critical for digesting food. But as a result, it also releases certain factors into the body. That much is well established. The key point is that your microbiome is going to be significantly different from mine. Can you modify it? We still don’t fully know.

That’s an example of how geography matters. Of course, genetics plays an important role too, but there’s increasing evidence that the environment is a critical factor in determining how patients respond to disease and how they survive.

SS: Migration has always existed, but in today’s world of globalization, it’s happening even more. Don’t you think that under such circumstances, the role of geography—or even history—goes down a little?

OR: I don’t think so, because the environment doesn’t necessarily change. The globalization you’re referring to is really about the movement of people.

For example, we know that when individuals from one country move to another, their disease risks may change. Take obesity: individuals from Asia who move to the United States and adopt the American lifestyle are more likely to become obese. That’s an environmental effect.

And the reverse is also true. If I come to your country, I may struggle with the food or the water because my microbiome isn’t adapted to interact with what I’ll be exposed to. That’s why, whenever I come to India, I’m extremely careful about what I eat and drink.

SS: What do you eat and drink?

OR: Well, I only drink bottled water—or boiled water—or hot drinks, which probably inactivate harmful bacteria. Otherwise, I could end up with a very unpleasant battle inside my intestines, and that’s an experience I’d prefer to avoid.

SS: Okay. What is the basic background of education in the USA right now?

OR: So, the way the U.S. system works—which has been extremely effective over the years—is this: there are four years of college, and then students decide whether they want to pursue a Ph.D., medical school, engineering, or any other path. In my opinion, it’s been one of the top places for learning and research, as evidenced by the international community that comes to the U.S. to study or advance their careers.

I also recently had a graduate student come from India who just started her Ph.D. in my group. So, I really like having an international community in my lab.

SS: As a guide, what factors do you look for? Or, what key words in recommendation letters help you decide whether to take someone or not?

OR: One word: Passion.

Passion for learning. Passion for research. Passion for motivation.

SS: Not exactly passion for the kind of work you do?

OR: Not necessarily. That’s something I can help guide the student or trainee toward.

SS: Okay. In India, in most universities, students are graded by percentage. Each semester or year, they get a percentage in various papers, which is then calculated through a formula. So, finally, you might get something like 75%, 80%, or 82%. Some institutes, like ours, use CGPA—Cumulative Grade Point Average. Each course is graded, then averaged into an SGPA (Semester GPA), and then all semesters together form the CGPA. That’s on a scale of 10. So, a student might get 7.5, 8.2, or above 9. Above 9 is generally considered very good. However, different institutes have different professors, grading systems, and standards. In some institutes, getting 7.5 means you’re an excellent student, while in others, unless you score 8.8 or above, it isn’t considered outstanding. So now, as a guide, when you’re evaluating a student’s transcript—say someone has a number out of 10, with individual course grades A, B, C, etc.—do those numbers strongly influence your decision to accept them or not?

OR: Yes. That’s an excellent question.I understand what you’re asking. The answer is—it’s unpredictable. You really don’t know until you put that person in a research environment, teach them techniques, and give them opportunities to apply their abilities.

That’s when the difference shows—their passion for the work.

I could see someone who is an excellent test-taker and who did very well in classes, but maybe they only enjoy the “book” side of things, not the hands-on problem-solving that research requires.

So it’s a difficult issue. For example, you could have one student with a 9 (on your grading scale) and another with an 8 excel once given that opportunity to really develop their scientific, you know, scientific focus.

SS: You said that’s your personal approach.

OR: Yes.

SS: But how does the system look at it? Because you’re also part of that system. There must be certain rules or norms of the institute, or the education department, that you have to follow. So how does it normally work?

OR: That’s a good point. It really depends on where in the system you’re trying to enter—as a student or as a trainee.

For example, when you think about graduate or undergraduate admissions, the school itself sets minimum requirements. You still have to show a certain academic level—good enough grades or test scores. A student with very low scores simply won’t even be admitted. So that already excludes a percentage of applicants.

On my side, of course, I wouldn’t take a student with extremely low scores because they wouldn’t even make it into the institution in the first place.

Now, if you’re asking what happens beyond that cutoff—who makes the actual selection? At the graduate level, that decision lies with the school. At the postdoc level, that decision lies fully with me.

SS: Fully?

OR: Fully—except for one thing. For international students, English is critical. They need to be able to read, understand, and discuss research in English.

We’ve had cases where a candidate looked great on paper—strong background, strong recommendations—but when tested on their English comprehension, they failed. That becomes a disqualifying factor.

So yes, there are institutional criteria that filter people out, but once those are met, the final decision for postdocs is mine, as the PI.

Now, if you’re asking about medical school—that’s a completely different process. There are standardized tests, letters of support, and interviews that weigh heavily in those admissions.

SS: Okay. So, let’s assume if I apply to you, I would first need to clear the English requirement.

OR: Yes.

SS: Should we discuss politics?

OR: If you want to discuss politics, that’s fine. You may not learn anything from me, but sure. What aspect of politics do you want to ask about?

SS: The same thing the world is looking into — what is America currently doing?

OR: I don’t know. Honestly, I don’t know. It’s… a sad situation.

SS: Sir, your research work has any connection, since you mentioned microbes, to what happened during 2019–2020 with COVID?

OR: Yes.

SS: Not in the sense of your research being interrupted by COVID, but scientifically — did the phenomena that came with COVID affect cancer in any way, directly or indirectly?

OR: Our direct studies don’t link to COVID. As you pointed out, the other side of it is that COVID certainly affected our research. But it’s not a research question that we are actively addressing.

SS: One more thing. During COVID, we all saw how doctors, sweepers, medical practitioners, and health workers were suddenly looked upon as heroes, even gods. Everyone looked up to scientists and doctors. Normally, scientists don’t get much recognition — it’s seen as just another regular job, often thankless. But during that time, people treated scientists almost like celebrities. From your perspective as an American researcher, did you ever feel that being a scientist was or was not a good decision? Did you ever feel that if you had chosen another path, you might have earned more money, respect, or power — things that might be considered more necessary?

OR: I understand what you’re asking. So the first part of my answer is: I’ve never looked back. I’ve never questioned my decision to go into research.

I’ve never thought of it only in terms of finances or the ability to make a living. And so I’ve never really been concerned about that. Let me pause on that for a moment.

Financially, I do pretty well. Could I make more money in industry or something like that? Probably. But I wouldn’t be as happy with what I do for a living. What I mean by that is, I get to decide what questions I want to ask.

I mentioned earlier that I was, for several years, at Procter & Gamble in the pharmaceutical research division. I was brought there to study obesity and develop therapeutics. That was awesome—I learned a lot.

But at the end of the day, they were making decisions to go in other directions with their research. So the choice of which projects to pursue was totally out of my hands.

Now, in academic research, of course, there are still things beyond your control—like convincing the community that what you’re doing is important. In order to get grants, you have to show that your work addresses a critical question. But beyond that, the decision about which questions we focus on—that’s mine to make.

SS: Aren’t there projects where your lab has to follow certain rules or directives? I don’t mean administrative constraints, not in that sense. I mean, suppose you’re part of a big project, or your department is involved in one. You’d need to align with what others are doing, follow the project guidelines, and work under that system. Have you ever worked in that way?

OR: To some extent, yes. What you’re describing is more of a team science type of project, where everyone has different components of the overall scheme.

Right now, for example, we’ve submitted a grant related to the microbiome with multiple PIs—principal investigators. Our overall goal is to understand the biology of the interaction between the microbiome and disease, in this case cancer.

We’re all focused on cancer, and we teach each other what we’re doing, helping one another ask bigger questions. So, to answer your question, in those cases, the overall direction is jointly decided.

SS: Would it be possible for you to give us your impression of how research in India is progressing? And what differences do you see between the Indian system and the American system?

OR: A little. The only thing I can really comment on, from my outside observations, is that the research here is of very high quality and has a very high impact. The challenge is that India is such a large country population-wise, and there simply aren’t enough positions for you and your colleagues to expand that research further.

I don’t know what the grant success rates are in India, but I understand it’s an interesting and different system. Many countries have their own structures that differ from the U.S. For example, when you’re a professor here, your salary is provided directly by your institution. That’s not the case in the U.S. In many academic institutions there, you have to write grants that partially support your salary.

It’s also different in terms of how students are funded. In the U.S., students are funded through grants or fellowships. If they don’t have those, the professor must support them through grants. I’m not fully versed in the Indian system, but I know excellent science is being done here, including through international collaborations.

The biggest challenge, as I mentioned earlier, is that many Indian fellows and trainees want to return to India after going abroad, but there are often no positions available for them. That makes it hard to retain or bring back talented researchers. But again, that largely comes down to the population size—you are a very populous country.

SS: What funding opportunities are currently available in the U.S. for students from the Global South, or so-called third world countries? I’ve seen many of my friends going abroad this year, mostly in chemistry and biology. But in physics and mathematics, it seems like opportunities are shrinking.

OR: Yes, those areas have been struggling, regardless of the international community wanting to work in the U.S. They’re inherently more difficult to break into here because there are fewer positions available. Historically, chemistry and biology have had a larger community due to demand, which has shaped the opportunities.

SS: Have you ever been to Europe, East Asia—Japan, Korea—or Australia?

OR: Yes, Europe multiple times. Asia and Australia as well.

SS: In the U.S., completing a Ph.D. usually takes five years. Sometimes it stretches to six or seven if you combine a master’s along with it.

OR: For which discipline?

SS: Generally, in science. Students do some coursework equivalent to a master’s degree and then continue with lab rotations.

OR: Yes, we call them rotations. I can speak specifically about the Ph.D. track.

SS: I’ll come back to my main question. In Europe, Ph.D.s usually take about three to four years. Why this distinction? What are the pros and cons of the U.S. system from your perspective as an American scientist?

OR: That’s a very interesting question. The U.S. system tends to emphasize the number and impact of papers a trainee produces, which often makes the process longer. Not always, but often.

There’s also a leveling process at the start. Students coming from undergrad don’t always have the same academic background, so the first year to year-and-a-half involves coursework to bring everyone up to speed. After that, the dissertation itself usually takes about three to three-and-a-half years. Publications are what ultimately earn you the degree.

In Europe, it’s different. I’ve often heard it said that in the U.S., the quality of education improves as you move upward: high school may not be as strong, college improves, and graduate school is even stronger. In Europe, however, high school and college are often very rigorous, but Ph.D. training may not be as intensive. That’s one reason why the U.S. has historically been seen as a superior place to pursue doctoral studies.

SS: Do you think someone earning a Ph.D. from Cambridge in the UK wouldn’t have the same edge as someone from Princeton in the U.S.? Let’s assume the same field, same quality of work. The only difference is the country and institution.

OR: That’s a loaded question. There are many aspects. If you’re asking whether I’d pick someone from the U.S. versus the UK as a postdoc—well, it depends.

Honestly, citizenship matters. If two candidates are equal in terms of papers and quality, the American has an advantage because they can apply for U.S. fellowships and grants, which foreign nationals can’t. For example, if an Indian student comes to me with an outstanding record but no independent funding, I’d need to find the money myself. But if they arrive with a fellowship from India or another source, that makes the process much easier.

So yes, sometimes the distinction isn’t about the quality of the Ph.D. itself, but about access to funding and ease of hiring.

SS: What’s your opinion about academic Ph.D.s versus industrial Ph.D.s?

OR: I can’t really speak much about the industrial side.

SS: Alright. Let’s move toward the conclusion. What would be your advice for students graduating now and heading out for their Ph.D. or postdoc?

OR: In the U.S. or globally?

SS: Globally, but the U.S. included.

OR: Okay. In the U.S., it’s a complex environment right now. Many students are choosing to take time off after undergrad—what we call “gap years”—to work in labs, gain technical experience, and then apply to graduate or medical school. That’s partly because the academic climate feels unstable at the moment.

Still, the opportunities in academic life are incredible. It’s highly competitive—no doubt, in India even more so—but the rewards and the richness of the experience are very high.

I’ll admit, I’m biased. But I believe the experience you gain in research is unlike anything else. My own children didn’t choose science, but I always tell them the same thing: choose something you truly love and feel passionate about.

I’ve never regretted my decision to become a scientist. Yes, I get frustrated when a grant is rejected or when reviewers are harsh. But I’ve never looked back wishing I’d taken another path, like medical school.

SS: Okay, sir. With that, we’ll end today’s conversation. We hope our readers will enjoy it. Thank you.

OR: Thank you. It’s been wonderful. You’re a great interviewer.