With Prof. Nagaraj Balasubramanian: On Cell Biology, Cancer, and the Joy of Doing Science

SC: Today, we have with us Professor Nagaraj Balasubramanian from IISER, Pune. He is a cell biologist, and we’re delighted to speak with him about his journey. Sir, when was the last time you visited IISER, Kolkata?

NB: This is actually my first visit. I’ve never been here before.

SC: Oh, is that so? How are you finding the conference?

NB: It’s fantastic. The campus is beautiful, very green this time of year—thanks to the monsoon, I suppose. I’m glad to be here.

SC: And your thoughts on BAW?

NB: It’s a wonderful initiative. I’m quite impressed by how a largely student-organized event has managed to bring together participants from all over the country. For students, it’s a tremendous opportunity. The focus on hands-on training and peer-to-peer learning is commendable. It’s great that students are involved in organizing and facilitating lab sessions too.

SC: Absolutely. Speaking of your journey, did you always aspire to be a researcher?

NB: Not really. I wasn’t very academically inclined in my early years. But around the 8th or 9th standard, I began to enjoy what I was studying—especially biology. That shift was largely because of a teacher, Mrs. Pillai, who taught biology in a way that deeply resonated with me. She’s no longer with us, but even after I completed my PhD and started my own lab, I would occasionally meet her.

Her influence stayed with me, and that’s partly why I chose to work in an institution that emphasizes teaching. When a teacher can impact a student’s life so profoundly, there’s a sense of responsibility—and privilege—to pass that on. That’s when I began to seriously consider research, though it took time to find clarity and confidence in that path. I also had one or two family members in research, so I had some idea of what the journey involved.

SC: So, are they also from biology backgrounds?

NB: No, they were physicists. But having them around gave me some sense of what a research career demands—how much effort it takes, how smart you need to be. That awareness was both helpful and intimidating. Sometimes it’s easier when you’re starting from a blank slate. Otherwise, you end up comparing yourself: “If this person is a scientist, am I good enough?”

But ultimately, it’s about getting the right opportunity at the right time. You apply to places, a door opens, and before you know it, you’re doing something you enjoy. And if you’re not overthinking it, you tend to just continue.

SC: So it all evolved organically?

NB: Yes, absolutely. Nothing was meticulously planned. It’s more fun that way, honestly. Today, I see many students who crave structure—knowing what will happen three months or three years from now. But science doesn’t always work that way.

To thrive, you need to be okay with uncertainty and still enjoy doing what you are doing. For me, it wasn’t about planning a career or thinking about salaries or perks. I just kept doing it because I was having fun. And I still am.

SC: And we can all see where you are now.

NB: Exactly. Every step—PhD, postdoc, returning to India—happened naturally. You apply, the opportunity comes, you take it. Things fall into place. I still think it’s a good approach, though I know it’s harder these days.

SC: It’s definitely more competitive now.

NB: Yes, and I understand why students feel the need to be more organized—earn degrees faster, have everything mapped out.

But my concern is: if you’re under so much pressure to do everything “on time,” are you even enjoying it? Because if you’re not, it’s hard to sustain. Structure helps with focus, but if it comes at the cost of joy, that’s a problem.

SC: You forget why you started in the first place.

NB: Exactly. That’s the key question I always ask students: Are you having fun doing this? If not, then none of the accomplishments matter in the long run. You can hit every milestone and still feel lost if the excitement is gone.

But if you remain enthusiastic, people notice. Whether you’re applying for a PhD, postdoc, or a job, yes, your intellectual abilities matter—but people are hiring people. They want someone who brings positive energy to the lab, who’s genuinely excited about their work.

So, while this approach may seem less structured, I believe it makes the journey more meaningful—and sustainable.

SC: So, why biology? What drew you to this microscopic world—especially as a cell biologist?

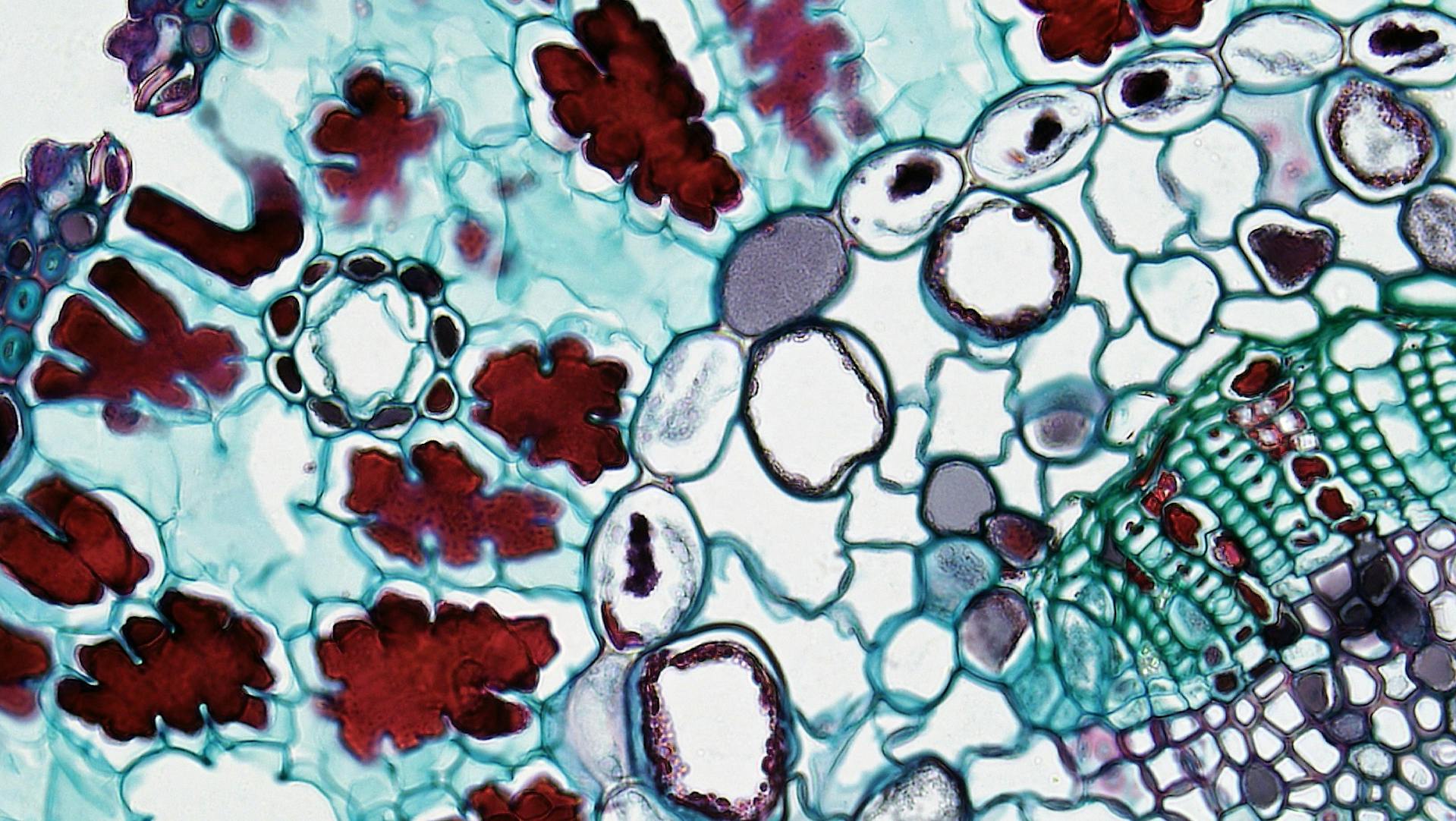

NB: I think it’s largely because there’s still so much to discover. There’s something magical about looking through a microscope and witnessing an entire hidden world. Personally, I’ve always been drawn to art, and I find great beauty in the images we capture in cell biology. That aesthetic appreciation has shaped much of my scientific perspective.

When you observe cellular phenomena—some of which have evolved over millions of years—there’s a sense of wonder that goes beyond just science. It’s like standing in front of a Van Gogh painting. There’s beauty and discovery coming together, which I think is quite unique to this field. That’s what really pulled me into it.

SC: You started working in cell adhesion and trafficking at IISER, right?

NB: Yes, my PhD was in a lab focused on cell adhesion. I spent those years understanding that space in depth. But after finishing my PhD, I wanted to step away from that area and try something completely different—thinking I might return to cell adhesion later.

That idea, in hindsight, sounds naïve. In today’s competitive environment, switching fields and then trying to return might seem like professional suicide. But I did it anyway.

SC: You were at the Cancer Research Institute at Tata Memorial Centre (TMC - now ACTREC) and then took a break from cancer biology, right?

NB: Yes. I moved to a lab that worked on mammalian phototransduction, which is worlds apart from traditional cell biology. It required me to learn new techniques and adopt a completely different way of thinking. Their questions and methods differed significantly from what I was used to.

At first, it was tough—new skills, unfamiliar concepts—but once I got through that, I gained not only new technical abilities but also a fresh mindset. That broader perspective eventually influenced my return to cell adhesion research.

When I decided to come back to that field, I identified a few top labs in cell adhesion and sent proposals. The first proposal I wrote was actually shaped by my experience in phototransduction—ideas about membranes that I had encountered there.

I sent the proposal to Martin, the top name on my list, not really expecting much. But within 15 minutes, I received a reply. I still remember the moment—I was too nervous to even open the email.

He wrote: “I’ve read your proposal. I have good news and bad news. The good news is, what you’re proposing is true. The bad news is—we just submitted a paper proving it.”

SC: Wow!

NB: Yes! But he added that they were working on other things and invited me to visit the lab if I was still interested. That experience changed everything.

What I learned is that stepping into a field you don’t fully understand can be daunting, but also incredibly rewarding. That ability—to be comfortable with discomfort and still learn—is critical for anyone wanting to do science.

Many breakthroughs happen at the interface of disciplines, where different approaches meet. So yes, maybe I got lucky. But maybe that “luck” happened because I took the risk to explore something new—and brought that back into my core research.

SC: So that transition actually fueled your return?

NB: Exactly. It shaped my ideas and opened doors I hadn’t imagined. That experience pushed us to explore areas we hadn’t previously considered. Today, we work on organelles I never imagined studying and even do a fair amount of computational work—which was not something I expected.

What made that possible was the confidence to say, “This looks interesting. I don’t know enough about it yet, but I can learn.” That mindset is incredibly important. It allows you to bring new knowledge into your primary field of interest, creating fresh insights and connections.

For students and young researchers, it’s critical to be comfortable stepping into unfamiliar territories. The most exciting science often happens when you bring two different areas together. You won’t be an expert in both, but being willing to learn the second is what expands your perspective—and your possibilities.

SC: Exactly—and once you do, your entire vision broadens.

NB: Right. The willingness to learn, and the confidence that you can learn, makes all the difference.

SC: I loved your talk today—especially the part on mechanosensing. Could you explain for our audience how mechanosensing is related to cancer?

NB: Sure. Cells are not just biochemical entities—they are also biophysical entities. Every tissue The Matrix in your body has a certain stiffness and structure. A liver feels different from a heart because of these physical properties.

Now, if you remove all the cells from a tissue, what remains is the extracellular matrix—a kind of structural shell that defines the architecture of that organ. This matrix influences not just the shape, but also how cells behave within it.

You know, there’s a movie called The Matrix—a classic from over 25 years ago—which plays on a similar idea: there’s this unseen system all around you that shapes everything. In biology, the extracellular matrix functions the same way. It’s present everywhere and affects how cells behave and how they interpret their surroundings.

It gives biochemical cues, yes—but also biophysical ones. Its architecture, shape, and stiffness all influence cellular behavior. So, it’s quite brilliant: the body uses not only chemical signals but also physical ones to regulate cells.

SC: And how does that relate to cancer?

NB: In cancer, this becomes very relevant. I used to work at Tata Memorial Hospital, and surgeons there would often say: when you physically hold a tumor, its stiffness often gives you clues about its aggressiveness. Over time, they’ve noticed correlations—harder tumors are often more advanced.

So, cancer changes the mechanical environment. Tumor cells grow and alter the surrounding matrix, often making it stiffer. But what’s more fascinating is how cancer cells adapt.

Unlike normal cells, which need a very specific environment to survive—say, a liver cell won’t grow in the lungs—cancer cells can bypass that restriction. They adapt to survive in environments with different biochemical and biophysical properties. They essentially override the usual requirement for adhesion and compatibility with the surrounding matrix.

One way they do this is by tolerating or even thriving in a broader range of stiffnesses. A normal cell will only grow within a narrow stiffness range—too hard or too soft, and it fails. But a cancer cell? It can grow just about anywhere—on soft or stiff substrates, or even on top of other cells.

SC: That adaptability is terrifying, but fascinating.

NB: It really is. That’s why we study not just the cell itself, but also the biomechanical properties of the environment it’s in. And it’s a two-way street.

The cell has its own stiffness too—it can be soft or stiff depending on what’s happening inside. And that cellular stiffness can influence how the surrounding matrix organizes and responds. It’s not just the environment acting on the cell, but the cell reshaping the environment.

So, this dynamic interaction between cell stiffness and matrix stiffness plays a critical role in determining how cells behave—especially in diseases like cancer.

SC: I have a follow-up: stiffness is a biophysical property—but how is it translated biochemically within the cell?

NB: That’s a great question. The key is that many receptors respond to both biochemical and biophysical cues—they don’t fall into neat separate categories.

Take integrins, for example. These are receptors that bind to extracellular matrix proteins—so, they clearly participate in biochemical interactions. But the same integrin, when binding to a stiffer matrix, can trigger a different response. It’s not about having a completely different mechano-specific receptor. Instead, the same receptor behaves differently depending on mechanical context.

SC: So it’s the receptor behavior that makes the process mechano-responsive?

NB: Exactly. There are some receptors or channels—like Piezo, a mechanosensitive calcium channel—that are distinctly responsive to mechanical stimuli. But most of the time, it’s about how regular signaling molecules and pathways integrate mechanical input alongside biochemical cues.

The key thing to understand is: the same pathway can respond to both types of inputs.

SC: So both the stiffness and the chemical environment affect the same pathway?

NB: Yes. In fact, many experiments that study cells on a matrix assume they’re only looking at biochemical signaling. But that matrix—especially on a plastic or glass dish—is extremely stiff, and that stiffness itself can activate signaling pathways.

So, when a pathway is activated, it might not be responding only to a chemical cue—it might also be reacting to the mechanical properties of the environment. Both cues converge on the same set of signaling proteins. You’re not activating one “biochemical pathway” and one “biomechanical pathway”—you’re activating one integrated response.

SC: And how do you observe the outcome of this dual signaling?

NB: All the cellular changes you typically associate with biochemical signaling—like protein phosphorylation, gene expression changes, receptor clustering, localization, or signaling duration—can also be triggered by biophysical cues like stiffness.

In fact, when cells are in their natural environment, they’re constantly exposed to both cues at once. The cell doesn’t consciously separate them—it just integrates the input and responds.

So, for example, if you expose a cell to a certain biochemical signal on a soft matrix, you may get one kind of response. On a stiff matrix with the same signal, the response may change—perhaps more intense or sustained. This is because the cell is integrating both types of information.

SC: But we’re the ones who try to deconstruct it as two different types of input?

NB: Exactly. We separate them experimentally to understand their individual contributions. But the cell doesn’t make that distinction—it just responds based on what it “feels.” And everything we study—whether it’s apoptosis, proliferation, migration—has a biomechanical dimension, because cells live in a mechanically dynamic environment.

That’s what’s so fascinating. Think about it—your bone is orders of magnitude stiffer than your skin. And yet, both support living cells. But if you swap the environments, say, place skin cells in a bone-like stiffness—they won’t survive. The same goes for normal liver or kidney cells in an unfamiliar environment.

SC: But cancer cells can?

NB: Yes, and that’s part of what makes them so dangerous. Cancer cells bypass adhesion-dependent regulation. Adhesion involves receptors like integrins, which “read” both chemical and mechanical cues from the environment. When cancer cells lose that dependence, they gain the ability to grow in new places, even if the stiffness and composition are drastically different.

That adaptability is what enables metastasis—and makes cancer so difficult to treat. These cells don’t care if the environment is soft or stiff—they just find a way to survive and grow.

SC: That’s incredibly moving. Was there a specific turning point when you knew for sure that research was what you wanted to pursue?

NB: It was more of a gradual realization. I had some exposure to research early on because I had one or two relatives who were in the field, so I had some idea of what a research career looked like. But it took me some time to gain clarity. During my undergraduate years, I was still figuring things out. Eventually, I got into a Master’s program where we had to do short research projects, and that’s when things started to click. I realized I really enjoyed asking questions and trying to find answers—that process of discovery appealed to me. That’s when I began seriously considering a research career.

SC: So I think a very simplified way to understand this is similar to the STRING analysis we currently use.

NB: Yes, absolutely. That’s definitely part of it. But now imagine scaling that up to the level of an entire cell—not just one pathway or one molecule, but the full complexity of a cell. We’re getting closer to having that capability. Right now, maybe only certain institutions with high-end computing power can do this, but very soon it’ll be available to anyone.

A graduate student sitting right here at IISER Kolkata could type in a well-framed query—specifying certain pathways or molecular players of interest—and the system could pull out all the processes and pathways likely to be perturbed or affected. Then the challenge becomes: how do you decide what to prioritize? What do you choose to study, and why?

In my opinion, any research aiming toward drug discovery is going to be dramatically influenced by this kind of integrative, AI-assisted analysis.

SC: That’s fascinating. I’m currently working on chemoresistance in breast cancer. Initially, I was assigned a different project, but I ended up exploring questions and directions that weren’t originally part of the plan.

NB: And that’s great. That’s exactly what research is about—being curious and following questions that matter. But let me ask you: in the context of chemoresistance in cancer, how do you decide which molecule to work on?

I assume it’s mostly based on your lab’s focus—you’re told, “We’re interested in this molecule, can you explore it?”

SC: Yes, exactly. That’s how it started. But it made me ask a deeper question—why are we even studying this particular drug in the first place? Why this one, and not another?

NB: That’s an excellent question. And I think the way you ask that question will look very different even just a year from now.

For instance, you can already go to platforms like DeepSeek and input a structured query: “I know A happens, I know B happens, and I suspect C might be important. Is there a pathway or process that connects these three observations?” DeepSeek will attempt to answer that, and the best part is—it shows you how it’s thinking.

It has a feature that reveals its internal reasoning — similar to what companies like Google DeepMind have demonstrated. It tells you: “Okay, based on your input, here’s how I’m connecting A, B, and C. Here’s what I looked at first. Here’s the network I’m building. Here’s how I’m linking these molecules.”

If you realize you’ve made a mistake—for example, that those three molecules are specific to breast cancer—you can recontextualize your query, and it recalculates based on that input. It’s incredibly intuitive.

SC: That sounds game-changing.

NB: It absolutely is. In many ways, it democratizes data analysis. You and I, sitting here at IISER, can use these tools. But so can a tenth-standard student in Rourkela—anyone, really—if they can frame the question well.

That’s the key skill going forward: the ability to frame questions correctly and in the right context. These tools can then provide the kinds of insights that used to take years of manual study. It’s not that the data wasn’t available before—it was. But now the effort to parse, connect, and extract meaning from it is drastically reduced.

So, the way we ask scientific questions is going to evolve rapidly—and I think that’s a very exciting shift for researchers everywhere.

SC: That’s how you frame questions—and the more you ask, the better you get at it.

NB: Exactly. Over the past 6–8 months of using AI, I’ve realized that how you phrase a question really determines the direction it takes. You can push it to think harder or more creatively. That means your interaction with it is shaping the answers you get.

As students, I think it’s crucial to engage with this now—it’s inevitable and already reshaping how we think and how we choose what to work on. Say you’re working on molecule X—if the AI can access and connect all existing information on it, regardless of when or where it was published, that’s incredibly powerful. How you frame or tweak the query becomes key.

Your insight then comes from understanding the players involved—evaluating each component independently before connecting them. We’ve done this in the lab. A couple of years ago, we had an idea and only recently generated the data to support it. The interesting question is: if we had framed that idea as a query back then, could the AI have pointed us in this direction? It’s a useful exercise—it helps us learn how to shape better questions that lead to meaningful exploration.

So just like we’re looking for new targets, pathways, or drug processes, AI is already influencing how we do science—and will do so even more in the future. This could help us select better candidates or ask questions we might have overlooked before.

SC: Or we might end up neglecting questions we would have otherwise asked.

NB: That’s true. The challenge is to streamline this—so if you move from one refined question to the next in a structured way, the answers you get will be more meaningful. I think AI will remain a tool, but companies will emerge saying, “We’ve figured out the smarter way to ask questions to get the best answers.” They’ll validate these systems—maybe show that their method leads to successful outcomes 80% of the time.

So it becomes about funneling the vast information efficiently to quickly arrive at something worth pursuing. That could change how we approach research entirely.

SC: And maybe in a few years we’ll see if that has a negative effect?

NB: Honestly, I don’t know yet. It’s definitely going to have an impact. Whether that’s positive or negative will take time to understand.

SC: Maybe we won’t even realize it—because we’ll be channelled into one dominant way of thinking.

NB: That’s a real possibility. But what’s certain is that it will change how we think. Right now, if you have three drug candidates and want to evaluate them under different contexts—say four parameters—and tell the AI, “These are the conditions I care about,” it can give you a well-reasoned answer. But you’ll still need to validate it. That part won’t go away. So, I believe, going forward, this ability to process vast data and narrow it down meaningfully is going to override almost everything. The science—yes, it’s important—but the way AI allows you to refine what you’re asking will change everything.

People like Demis Hassabis, who shared the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for AlphaFold — the protein structure prediction AI developed at DeepMind (Google’s AI division), predict that by 2030, we’ll see intuitive AI—systems that learn how you think and anticipate your patterns. That’s big. It means it may one day understand your style of reasoning.

SC: Do you think that’s too much power for the world to handle?

NB: It’s coming, whether we like it or not. So we’d better learn to work with it—and use it creatively, to push forward what we’re trying to do. Yes. And you’re also not sure you’ll get there. In many ways, it’s like blind faith—you believe you’ll learn the method, that you’ll get there eventually. But there’s no guarantee.

And it’s not for everyone. Some people will make it, some won’t. But when someone does achieve something, you can tell—it feels elusive and remarkable. That’s the interesting parallel I see between science and art.

There’s a huge amount of uncertainty in both. For example, when you submit a paper—even if you’re a Nobel laureate—there’s always a question: will it be accepted, will it be understood the way you meant it? Sometimes ideas take decades to be appreciated.

Like in art—Van Gogh didn’t sell his work, didn’t get recognition in his lifetime. Maybe if people had acknowledged his genius, it would have changed his life. But it took 50 or 100 years for the world to understand what he had created.

He died not knowing how impactful his work would become. That’s true in science too—you do your work with good intention, publish it, and move on. Who knows? A century later, someone might look at it and say, “This is incredible—they were ahead of their time.” But you’ll never know.

SC: That’s beautiful.

NB: So I think the parallel between science and art is very real. And when something remarkable happens—whether in art or science—for me, it feels like lightning striking. It’s magic, built on years of training, experience, and effort. But even the creator didn’t fully know they were capable of it.

That’s what I feel when an experiment yields something extraordinary. You follow the method, trust your instincts, and do the work with care. You hope it leads to something unique. Sometimes it does, sometimes it doesn’t.

Many artists and scientists have lived their whole lives dedicated to their work without ever being recognized. But they still did it—for exploration, for the belief that it mattered. That, to me, is the connection between the two worlds.

SC: Have you pursued any other creative interests beyond academics?

NB: I used to paint. I still sketch occasionally, but these days I mostly do photography. So yes, I’ve always kept a creative pursuit alive.

I think it’s important for scientists to have something creative outside of their research. You may not always see it that way, but the very act of doing science requires creativity. I don’t think there’s a single scientist out there who is completely devoid of it. It’s about discovering and nurturing that part of yourself.

We are wired to think creatively—that’s what makes scientific exploration possible. So having a creative outlet helps. It has always helped me.

SC: Sir, moving from that—many people outside the world of science often feel estranged from it. What would your approach be to bring science closer to the general public?

NB: I think, first and foremost, we scientists have to be approachable. Science, much like art, is a deeply isolating pursuit. When you’re building an experiment or crafting a research narrative, it often happens in solitude. Others may support you, but the core of the work is yours alone.

Many scientists are comfortable being alone, lost in their thoughts. That’s part of the reason why we may appear aloof or uninterested in engaging. People often hesitate to approach scientists, partly because of the perception that we’re intellectually distant or hard to relate to. If we also come across as unapproachable, that only reinforces the gap.

That’s why the onus is on us to change that perception. If people feel you’re open to answering their questions, they’re more likely to ask. It’s important, especially today, for the general public to understand what goes into scientific work—the persistence, the setbacks, the drive. It’s not just about funding. Yes, money matters, but the personal investment, the dedication of the scientist—that’s what truly drives discovery.

But people outside the field won’t know this unless we talk about it. Every interaction is an opportunity to bridge that gap. You meet someone on a train, and they ask what you do—that’s a moment to connect. Just like this conversation: I could be doing something else right now. But if even two people listen and come away with a deeper understanding of science and what it takes, then it’s worth the hour or hour and a half.

Everyone connected to science has a responsibility to communicate not just what we do, but how we do it—and why it matters. People celebrate athletes as national heroes, but how often is a scientist publicly recognized or celebrated? That needs to change.

If we’re out there telling our stories—sharing the challenges, the breakthroughs—then people will start to see science differently. The excitement of discovery, the thrill of overcoming obstacles—if that’s communicated well, people will feel connected to it.

That’s why athletes resonate. You saw Suryakumar Yadav take that incredible catch, and it made you feel something powerful. So naturally, if you met him, you’d want to shake his hand. Science should aim to evoke that same feeling—that awe, that thrill of achievement. If we can make people feel that about science, then maybe one day someone will shake a scientist’s hand and say, “I read about what you did. It was incredible.” That’s why this kind of communication matters.

SC: One last question, can you tell us more about the International Conclave on Citizen Science happening in July?

NB: Sure. It’s being organized by the Pune Knowledge Cluster, and I believe this is the first time they’re holding such an event. There are many citizen science initiatives across India—and globally—like iNaturalist, which I use a lot. You can upload photos of plants, moths, or birds, and it identifies them using existing databases. It even shows distribution data and other nearby sightings.

So, the idea of the conclave is to bring together various citizen science projects and talk about how these initiatives contribute to scientific understanding. It’s also a platform to share ideas and experiences from different regions and disciplines.

SC: Oh, like an exchange of ideas?

NB: Exactly. It’s about sharing how these projects work and how citizen involvement can support scientific research. There are such initiatives in India too, and I think it’s important we talk about them. It’s an exciting first-time effort. Where did you come across it?

SC: Sir, thank you so much. This was a really amazing session. Any final thoughts or a message for us research students?

NB: Enjoy the process. You’re in a very privileged space - to be able to ask questions that you’re curious about, and with some luck, even make a profession out of answering them. That’s rare.

It won’t always be smooth. Things won’t always go according to plan. But if you truly enjoy what you’re doing, you’ll always find a reason to keep going. And that’s what makes this sustainable.

Don’t pressure yourself too much with timelines. I see a lot of students telling themselves, “If I don’t get here in five years, I’m a failure.” That’s not true. Even ten years can feel short if you enjoy the journey. But if you don’t, even six months can feel unbearable.

It’s like someone learning music saying, “If I train for ten years, will I sing like Kishori Amonkar?” No one can promise that. Not even Kishori Amonkar knew she’d become who she was. All we can do is teach you the tools, and if you enjoy the journey, maybe you’ll go even further. But it’s the joy in the process that matters most.

SC: Yes, it might or might not happen.

NB: Exactly. That uncertainty is part of the journey. If you let that uncertainty weigh you down every day, it’ll stop being enjoyable—and then it’s not sustainable. So, find a way to enjoy what you’re doing. Everything else will follow.

SC: Thank you so much. This was truly inspiring.

NB: Thank you.