From IISER Kolkata Transit Campus to Tel Aviv: Rajarshi Bhattacharyya's Academic Voyage

SS: Hello, I am Swarnendu Saha from InScight and today I invite you to this interview. Rather than thinking of this as an interview, please consider this as our attempt to understand how the present IISER Kolkata appears in the eyes and views of an alumnus.

RB: Thank you Swarnendu. It is a great pleasure for me to meet you. And as I mentioned earlier, I also see this interview more as a platform of interaction rather than a so-called interview. And I am absolutely happy to share my experiences and address your questions about my experience and everything, basically everything that you have in mind. Please start.

SS: I believe you joined here in 2010 and passed out in 2015. So, I think you did not see this building as a student.

RB: (smiling) I did see this building as a student and I will tell you why. During my five years here in IISER Kolkata, in the beginning, there was a transit campus that was leased from BCKV. And at that time, around 2013, there was an active movement of moving the labs and everything on the infrastructure slowly towards this permanent campus.

The permanent campus was already in a build up phase during 2011-2012 and in 2013, the movement started. So, I lived both in the old campus and in the new, in different phases of my student life. Ishwar Chandra Vidya Sagar hostel was not there. at that time. So, in between the boys and the girls hostel, there was this canteen at the ground floor. And on top of the ground floor, there was lecture hall complex 4.

SS: So, since you have actually seen, what the differences were of these two campuses and how the student life was different in both, if it was at all. And after 10 years, when you stand today, how is the difference?

RB: Looking back about ten years to 2012–2013, the campus was in its developmental phase. The permanent campus was somewhat messy due to ongoing construction, whereas the transit campus, though more organised, was spatially constrained. Laboratory space and classrooms were notably small, leading to frequent complaints.

The transition to the permanent campus brought significant improvements, particularly with the large lecture hall complex, which could accommodate around 200 students. This was a stark contrast to the transit campus, where such capacity was impossible. In 2010, batch sizes were around 100, but by 2013–2014, they had exceeded 200, making the expanded facilities essential.

Another key difference was recreational space. The transit campus had some play areas, including a badminton court near AJC Bose Hall. There was also a popular tea stall and a small, shaded eating area, which were well-loved by students. A food outlet initially operated inside the transit campus before moving outside. These informal gathering spots were particularly cherished by many.

SS: We had Bimalda, I mean we still have it, it is now in cafeteria form. I have seen Bimalda’s old shop.

RB: Right, right. But one thing that I can definitely say is the hostel life in the older campus at that time, at least that is what we realized, was really a little bit different than the hostel life in the new campus. It was a little bit more messy, but it was more enjoyable at the same time.

In the transit campus, student life felt more independent. The hostel was separate from the academic buildings, making it a space for personal activities like photography and other hobbies. Many students, especially nature photography enthusiasts, cherished this freedom and saw the hostel as their own space.

The transition to the permanent campus brought more organisation, but with that came restrictions—security regulations, permissions, and a structured environment. While this had its advantages, it also felt more constrained compared to the free-spirited days of the transit campus. It’s similar to how people cherish music from their formative years—familiarity makes it special. For those who started in the transit campus, that environment holds a unique place in their hearts.

Looking at the permanent campus over time, it’s now far more structured and truly resembles an IISER campus. In the early days, buildings were scattered, and not all facilities had moved from the transit campus. Today, everything is well-organised. Students likely appreciate this structure, with amenities like a badminton court inside the lecture hall complex.

On the way to the research hall complex, I also noticed a school, which had started earlier but is now fully operational. There are surely more changes I haven’t explored yet, but the main transformation has been in the structured development of the campus.

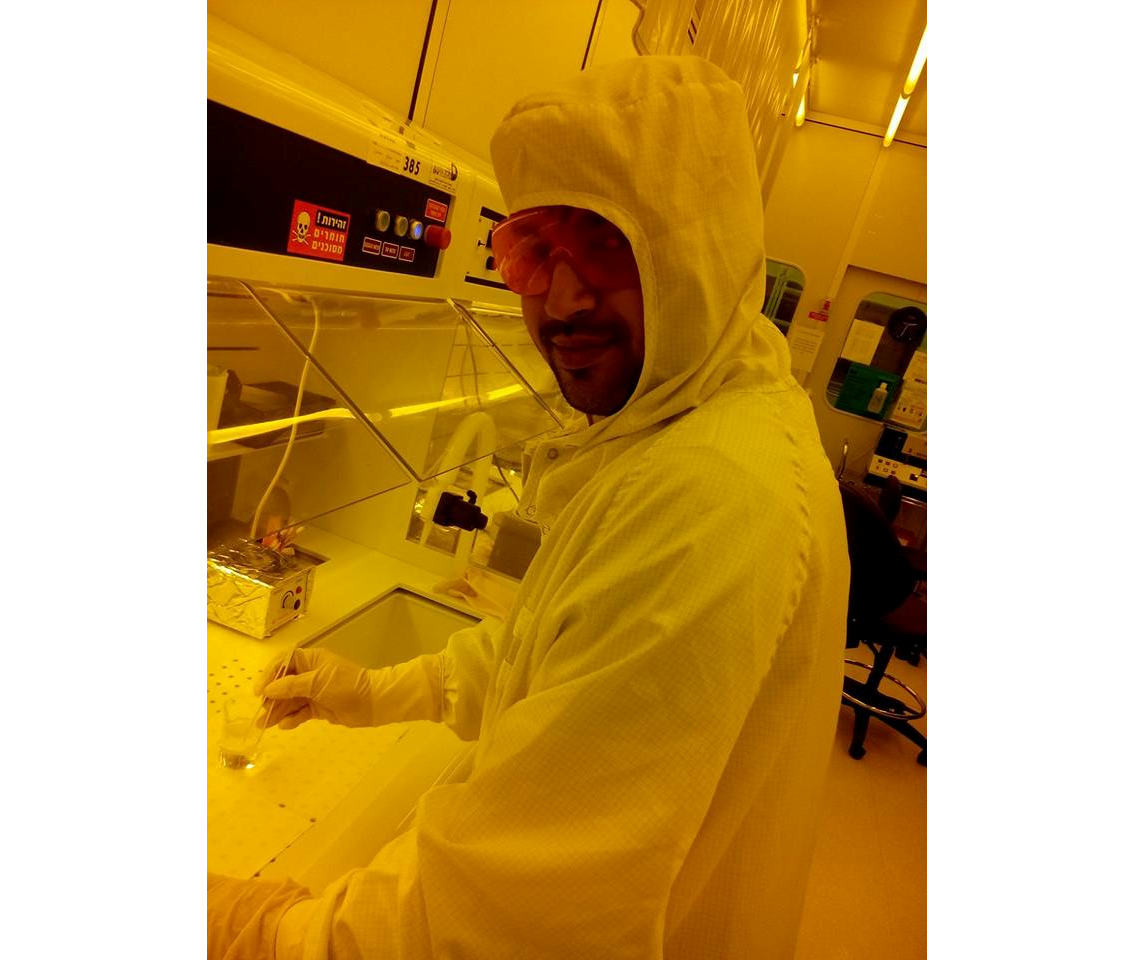

SS: Can you tell us briefly about your academic journey, starting from your schooling? I believe you carried out your doctoral studies in Israel. Israel is of course also in the news for the Israel-Gaza war. Can you please describe whether those issues affected you and your work?

RB: My schooling was spread across different locations. Until Class 7, I studied at Barrackpore Mission, after which I moved to Malda Ramakrishna Mission for Classes 8 to 10 due to my father’s transfer. Later, I returned to Barrackpore and completed my higher secondary education at Barrackpore Government School. After that, I joined IISER Kolkata, which played a crucial role in shaping my scientific interests. Unlike school, which primarily focused on syllabus-based learning and rote memorisation, IISER Kolkata provided my first real exposure to scientific experiments, critical thinking, and research methodologies. It was here that I truly understood how to think scientifically, a process that deeply influenced my decision to pursue research as a career. However, not all students from IISER Kolkata take the same path—many explore diverse career options beyond academia.

When considering a PhD, I had multiple offers from leading European institutions, including EPFL in Switzerland, Ulm University in Germany, and an institute in Israel. After evaluating my options, I chose Israel because the lab I was offered a position in was one of the best in its field. If you attend my talk, you might get a better sense of its significance. While I was aware of the regional conflicts, particularly the 2014 Israel-Gaza war, it did not deter my decision. A common misconception, especially in Bengal, was that Israel was a Muslim country due to its Middle Eastern location. In reality, Israel is a Jewish state, founded in 1948, with a distinct cultural and scientific identity. I even had to convince my parents by showing them evidence that it was not a Muslim-majority country.

Another key reason for choosing Israel was its strong reputation for scientific excellence. Around 27% of Nobel laureates over the past 50 years have been Jewish, despite Jews making up only 0.01% of the world’s population. This reflects a strong intellectual culture where intelligence is not inherited but cultivated through rigorous training. Beyond research, what I truly gained in Israel was an invaluable approach to problem-solving. The mindset there is to face a problem, solve it, and move forward, rather than bypassing it. This systematic way of thinking extends beyond science and is deeply ingrained in their culture.

In summary, my journey from school to IISER Kolkata and eventually to Israel was driven by my passion for scientific exploration and a desire to develop a structured, problem-solving mindset. This experience has profoundly shaped my academic and intellectual growth.

SS: Before going forward, I would request you to explain to our readers what your area of specialization is. How has that shaped you, and have you had a chance to maybe shape the field in some way?

RB: Sure. Okay, again, this question has multiple parts, so I will try to split them up and then answer one by one. The first question is my area of specialization.

In a very, very broad category, it’s experimental physics. If you try to narrow it down a little bit, it’s condensed matter physics. If you narrow it down further, it’s called mesoscopic physics.

Mesoscopic is basically a scale which is not really, which is not nanometer scale, which is neither nanometer scale nor microscopic scale. So, it’s like, it’s like a sub-microscopic scale and it’s called mesoscopic basically, which means the samples that we deal with are of the order of, let’s say, hundreds of nanometers to, let’s say, a few micrometers, something like that. It’s not angstrom scale, neither it’s like a macroscopic scale. It’s somewhere in between.

SS: Since our magazine targets people from various backgrounds, can you please explain mesoscopic physics and its scale using a real world analogy?

RB: That scale would be compared to, let’s say, the diameter of our hair. I mean, that can vary depending on the strength of the hair. The diameter of typical hair is of the order of a few tens of micrometers.

Now, our scale starts at, let’s say, around hundreds of nanometers and goes up to, let’s say, hundreds of microns. So, it is within the, somewhat in the visible region? Not with the naked eye but yes, with the optical microscope, you can somewhat see it.

Of course, hundreds of nanometers or hundreds of nanometers, you can only probe it with, let’s say, electron microscopy. So, that is my area of expertise and it is basically the scale that I talked about, now my particular area of expertise if you narrow it down further, it is called transport physics, where you basically make transport experiments on your system in the sense that you probe it using current and voltage measuring methods.

SS: I guess what you mean to say is that when there is a transport before, after, during these phases you will see how the voltage and the currents vary and on the basis of this you go on further.

RB: In my research, I focused on investigating phase transitions using transport experiments. This involves sending tiny electrical signals—either current or voltage—through a sample to probe phase transitions with high precision. If the signals were too strong, the transitions would blur out, making them difficult to study. These sensitive electronic experiments allowed me to explore energy scales relevant to phase transitions. My work was specifically centred around quantum Hall physics, a phenomenon best observed in two-dimensional heterostructures. While graphene research was growing at that time, 2D heterostructures remained one of the finest systems for studying the quantum Hall effect. However, these effects only manifest at extremely low temperatures, so all my measurements were conducted at temperatures as low as 10 millikelvin. You will see these temperature scales referenced in my talk as well.

Regarding how my PhD shaped me, I like to think of it as a rigorous training process. People may have different opinions, but in many ways, I find a PhD training comparable to army training. While army training disciplines the body and mind through physical and mental endurance, a PhD is a training of the intellect—a systematic process of learning how to think intelligently and approach problems in an analytical way. It is not just about the number of hours spent working in the lab; rather, it is about shaping the way one thinks and processes complex challenges.

Through this journey, I realised that a PhD is essentially a training of thought—an intellectual discipline that prepares one to tackle any problem, whether in research or beyond. I am particularly glad that I chose Israel for my PhD because, as I mentioned earlier, the mindset there is distinct. People, regardless of their profession, tend to address problems head-on, solve them, and then move forward. This approach left a deep impact on me, and I believe it is one of the most valuable aspects of my training.

SS: If you don’t mind me interrupting you, I would like to add something. Israel, after its birth, had to face many hurdles. I believe I am correct when I say that they have a minimum 2-3 years of mandatory military service, and you seem to be saying they have this mindset of solving any problems they face. If possible, they fully eliminate it. Do you think the experiences and history of the Israelites somehow shaped this mindset?

RB: Absolutely. And maybe as you speak of it, it’s possible that because even now in Israel it’s a mandate that every citizen over there unless he is an orthodox Jew or have some other kind of disability or whatever has to mandatorily go through a military schedule like let’s say at least he has to serve in the military for 2-3 years depending on the gender. This at a very early age for example after 18 and only after that people decide which direction to go like research or industry whatever or to do some further studies or whatever.

It’s probably this military training that they get at this early age has quite some influence on them to develop this mindset of solving a problem one shot when they stumble upon something like that. So this thought process is definitely my PhD career over there. I would definitely, I can definitely see that development in myself about how to approach a problem, how to tackle a problem, how to even think about a problem and then step by step coming into the conclusion.

It’s really something that comes from that training part. Of course it has another mix you get really a good exposure into research but these are things that everybody knows. Mostly it’s a training period, that’s what I would like to think about it.

The third part is how you would say that I might have shaped my particular field. I would say every PhD student shapes its field in one way or the other because a PhD, what does a PhD mean? A PhD means that you can think of it in a geographic way like let’s say there’s a circle of knowledge which is pre-existing and you are inside and your idea of doing the PhD while being inside the circle would be to expand the boundary no matter how small or how large it is. That is the idea. The moment you are able to expand the boundary of that knowledge you will be called a PhD. This is the ideal case.

Of course there are many different circumstantial issues that come into the picture but this is the ideal, this is the idea of being a PhD that the idea is that the moment you are able to push the boundary you are called a PhD. So in that sense I would say every single PhD in the world has shaped the particular field that they have worked on and I probably won’t be an exception in that sense.

SS: Moving on to other stuff, have a couple of short questions, particularly from the perspective of prospective PhD applicants. You applied to both Europe and Asia—specifically Israel—so how would you compare the application processes? How did the individual steps, such as CV preparation, contacting professors, and selecting an institute, differ between these regions? I ask this with the hope that your insights will benefit future applicants. While students at IISER Kolkata are somewhat aware of opportunities in Israel, the most common choices for PhD aspirants tend to be the US as the primary target, followed by Europe. The order may sometimes vary, and occasionally, students consider Japan or Australia, though these are less common. However, Israel is not typically on the radar for many students outside IISER Kolkata. Even within IISER, interest in Israel as a PhD destination, while present, is comparatively lower.

RB: The answer to this question is quite detailed, and I am not sure how much time we can allocate to it. However, I will try to keep it as concise as possible while providing my perspective.

One of the first things to consider when applying for a PhD is the choice of place—the lab you will be working in, the level of research, and the quality of work happening there. Unfortunately, after spending five years in IISER Kolkata, where students undergo rigorous coursework and gain some research exposure, they are suddenly confronted with the harsh realities of the outside world. These realities include multiple factors that influence the decision-making process.

For instance, if your long-term goal is to become an independent researcher—say, a faculty member in India—there are two main pathways to consider. The first is pursuing a PhD in India under a renowned professor who has a strong research output and a well-established lab culture. However, finding the right mentor in your specific area of expertise can be challenging. If you do secure a PhD position in such a lab, it can significantly boost your future career prospects because you will already be recognized in the research community during your PhD.

The second pathway is pursuing a PhD in a top lab anywhere in the world—whether in the US, Europe, Japan, or Israel. If you secure admission in a leading research group, the location does not matter. Ultimately, merit speaks for itself. However, securing a position in a top lab is not always easy, as availability depends on funding, timing, and competition. A lab might not have an opening when you apply, or you might not apply to the right lab at the right time. Being the right person in the right place at the right time is crucial for success.

If a candidate is unable to secure a position in a top-tier lab, practical considerations come into play. The structure of PhD programs varies significantly between different regions.

In Europe, PhD positions are often based on fixed-term contracts with a specific professor, typically lasting three to three-and-a-half years. Once the contract ends, the stipend stops—unless the professor has additional funding. This system requires students to complete their PhD within the contractual period, which can be a challenge. Moreover, in India, such short-duration PhDs are sometimes not considered equivalent to a full-fledged PhD. Since coursework is often minimal or absent in European PhD programs, these shorter PhDs may be perceived as premature or incomplete in the Indian academic system.

This is one of the reasons why many students prefer the US for PhD programs. The US PhD system follows a graduate school model, which provides a structured environment with coursework, research, and teaching assistantships over a typical duration of five to six years. In my case, I did not apply to the US primarily because of the GRE requirement, which I did not find to be a fair evaluation system at that time. That said, the US model has both advantages and disadvantages.

One challenge for PhD students in the US is that survival often requires additional work beyond research. Depending on the university and location, students may need to take on multiple responsibilities—such as teaching assistantships, coursework, and sometimes even part-time jobs—to sustain themselves financially. This extra workload can affect the quality of research, as students need to balance multiple commitments alongside their PhD work.

From this perspective, Israel offers a balance between the US and European systems. While European PhDs are shorter and contract-based, and US PhDs are longer but come with additional commitments, Israel falls in a sweet spot. The PhD structure in Israel provides adequate research time without the additional burden of extensive teaching or coursework requirements.

Additionally, for students from IISER Kolkata, there is another unique consideration. IISER students already graduate with a master’s degree (BS-MS), but US PhD programs often do not require a master’s degree for admission. This means that IISER students are technically overqualified when applying to US graduate schools, as they already possess a master’s degree but would still be required to enroll in a program that includes a master’s component.

That’s why actually in RISC towards I think in 2011 or 2012, I don’t recall exactly, they started a four-year BS program and that’s very well suited for particularly for students who want to do a PhD in US, because they can do a four-year BS from here and then directly join a PhD there and get a master’s degree together, okay. So, here you are giving it one more year, acquiring a master’s degree and then you are going for a PhD, so it’s this one year, it’s there, that you are giving time to ISF Kolkata. So, yeah, all in all, this is basically, okay, so sorry, I was talking about Israel, why it’s in a sweet spot is because it’s not the contractual thing, so if you go to Israel, you will be guided for your PhD by a grad school system, apart from your own mentor for your PhD, there will be two other guides from the grad school system, who will overview your PhD work throughout the whole time.

SS: That sounds like our practice of conducting research progress committee evaluations every year.

RB: In Israel, the PhD system is somewhat similar to the graduate school model in the US, but with key differences. Two professors are typically assigned by the grad school system to oversee a student’s PhD progress throughout their research. At the Weizmann Institute of Science, for example, the average time to complete a PhD is four and a half years. While I cannot confirm whether the same structure applies to other institutions like Hebrew University of Jerusalem or Technion, I do know that the overall PhD duration in Israel strikes a balance—it is neither as short as three years (as in some European programs) nor as long as six years (as in the US).

Another advantage of doing a PhD in Israel is the manageable coursework requirement. At Weizmann, students need to complete 12 credits, which typically translates to four to five courses over the entire PhD duration. This is relatively light compared to the coursework burden in the US. If a student chooses to complete these requirements within the first three years, it averages to about one and a half courses per year, leaving ample time for research.

Of course, given the current situation in Israel, prospective students might find it a difficult decision to pursue a PhD there. However, history has shown that tough times do not last forever, and I strongly believe that once this challenging period is over, the situation will stabilize. When I pursued my PhD in Israel, I was able to complete it peacefully without facing any major disruptions. I am confident that Israel, known for its resilience and innovation, will navigate through this phase successfully. The recovery is not a matter of five or ten years—things are already in motion, and stability will return soon.

SS: Okay Dada, so it was nice to talk to you. Any last comments for our students?

RB: I can wish them all the best for sure for their future endeavor, whatever career path you choose for yourself, it doesn’t matter, you can choose PhD, you can choose MBA, you can choose to have your own business, whatever career path you choose, just try to self-teach yourself the thought process of training yourself to have an intelligent way of approaching any problem, as intelligently as possible. By saying as intelligently, it means saving as much time and resources and that basically, I mean your specific problem is your specific thing to solve, but this is the general thing that you will find that it would be very useful for yourself.

SS: Thank you so much.