Meet Prof. Sanjit Mitra, the Science Spokesperson of LIGO India

SS: Welcome, sir. I am Swarnendu Saha from Team InScight, and today I have the privilege of engaging in a conversation with you to explore your journey and gain some insights that may guide us forward. We’d love to talk a bit about your academic background, your research, and, if possible, take just a little of your valuable time. Let’s begin with some basic questions. Could you please tell us where you come from and walk us through your academic journey, starting from your early years? How did you arrive at where you are today - what were the key steps or decisions along the way?

SM: That’s actually a long story! Initially, I wanted to pursue engineering. But back then, I barely knew any chemistry. So, the chances of getting into an engineering program were quite low. I thought, “Maybe I’ll take a year, prepare well, and try again next time.” This was during my Class 12 days - I passed school in 1993.

At the time, we had Physics, Chemistry, and Mathematics. Chemistry was a subject, yes, but I really didn’t know much about it. I was only interested in Physics and to some extent, Mathematics.

SS: So you didn’t like Chemistry at all? Maybe even wished it wasn’t there?

SM: [Laughs] Yes, exactly. I knew very little, and I wasn’t fond of it.

Anyway, I planned to spend the next year preparing for entrance exams. But in the meantime, I thought of taking admission to a nearby B.Sc. college. That’s where I met two teachers who left a lasting impression on me - Kiranmoy Sen Sharma and Subir Ghosh. Their teaching was so inspiring.

SS: May I ask where this college is?

SM: Yes, it’s quite close to my house - about one and a half kilometers away.

SS: In Kolkata?

SM: Yes, in Kolkata. So, what happened was - they started teaching mechanics and related topics, and I found it really quite interesting. Then, I think in the second year, they introduced quantum mechanics and so on. Actually, even in the first year itself, I became quite engaged with the subjects.

Gradually, I lost the motivation to appear for the engineering entrance exams again. I thought, “No, I’ll drop that plan.”

At that time, the University of Calcutta had this option - after completing a three-year B.Sc. degree, you could pursue a B.Tech in Radio Physics, Electronics, and similar fields. So, I started thinking, “Maybe I’ll go for that instead.”

SS: Okay, so was it that you didn’t want to appear for the entrance exams again, or was it more because you started enjoying the subjects in physics?

SM: It was mainly because I started liking physics. I had initially thought of going into radio physics and related fields, but in the third year of B.Sc., we started learning topics like relativity and quantum mechanics - really fascinating subjects. Once I got into those, I felt it would be very difficult to leave physics behind.

I still considered going into radio physics, but my marks weren’t that great. So, I thought - forget everything else, I’ll go for an M.Sc. in physics instead.

So, I enrolled in the M.Sc. program. Around that time, I had a friend - I had a brief overlap with him in Class 11 - he was in the M.Sc. as well.

SS: Where did you do your Class 11?

SM: I did my Class 11 at St. Xavier’s College, but I had known this friend from Jodhpur Boys’ School. It’s a long story [laughs]. Anyway, he was already at that college and also joined the M.Sc. program. He told me about this place called IUCAA - he suggested I attend a summer school there.

I thought, “Okay, he’s quite knowledgeable, so I’ll follow his advice.” I applied and went to the summer school at IUCAA at the end of my first year of M.Sc. - and I found it to be a wonderful place!

That’s when I decided: I should do my Ph.D. there. Of course, I had to clear all the competitive exams and go through the usual process.

SS: So even back then, you had to appear for exams like NET and GATE?

SM: I gave JEST, NET - these two exams. I also applied for TIFR and other places. But IUCAA was just too good, very comfortable.

SS: So, you were a student at IUCAA, and now you are a faculty member there. Correct? Over these long years, how has IUCAA developed and evolved? Also, how is an institute like IUCAA different from universities such as Calcutta, Bombay, or institutes like IISER, IITs?

SM: First, let me tell you something - IUCAA hasn’t really changed much, and I have a theory about that. IUCAA was founded by Jayant Narlikar, who believed in the steady state theory, so maybe that’s why! [laughs] But seriously, there have been changes, though I’d say they are relatively minor.

What has really changed is how science is done. Science itself is always evolving, but recently, collaborative science has become much more prominent. By collaborative, I mean scientists working on different parts of a project come together and pool their expertise.

For example, I was part of two major projects: the LIGO project and the Planck project. These kinds of large collaborations have always existed, but over the years, the number of people involved has grown significantly. Take LIGO - there are over 1,000 people in the collaboration! Think about how many astronomers there are worldwide; that shows the scale. And LIGO isn’t the only one - there are other collaborations too, like in radio astronomy and Planck, which had a few hundred people.

This shift means that the era of a few “star” scientists leading everything is fading. Instead, we have groups working together, and the work is more distributed. Along with that, the number of astronomers in the country has probably increased, so that has also contributed to the change.

SS: I had a conversation with Professor Nissim from NCRA. He mentioned that depending on who is the director or the main guiding person of an institute, the nature and functioning of that institute can change. But you’re saying that over the years, science itself has evolved, while IUCAA has not changed that much?

SM: Right, the administration of the institute - how it operates - does change. The amount of time you get for research can vary; sometimes you get more, sometimes less. But scientists are probably the most difficult people to convince to change. Getting them to do something other than what they want to do is almost impossible.

On the the other hand, directors have to optimise distribution of resources based on the goals of the institute and priorities of the researchers, which can impact research highly dependant on, say, experimental or computational facilities. But that maybe inevitable since the resources are limited.

SS: So, you said funding can affect research, but it hasn’t affected you much personally. However, when I talk to other professors or researchers at IISER or elsewhere, many say funding issues have affected them a lot over the years.

SM: Yes, especially for experimental work, funding matters a great deal. If your experiment needs ten components and you get only nine, your experiment simply can’t happen. You might make some progress, but you can’t complete it. Funding is crucial.

Maybe I’m saying this because I was fortunate - LIGO India got funding, so that helped. Also, institute directors decide whether their institute will join these mega-projects, which changes the institute’s dynamics somewhat.

For example, IUCAA is part of LIGO India. If I weren’t involved in LIGO India, I’d probably spend more time on different gravitational wave research. But since IUCAA is part of LIGO India, I spend a lot of time working on the collaboration - even if it doesn’t immediately lead to publications, it’s important collaborative work.

SS: Okay, so for our friends from other disciplines, what does LIGO stand for? What is LIGO, and what is LIGO India? Are they the same thing?

SM: LIGO stands for Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory. It’s a highly sensitive detector designed to detect gravitational waves directly. Currently, it’s the most sensitive instrument of its kind in the world.

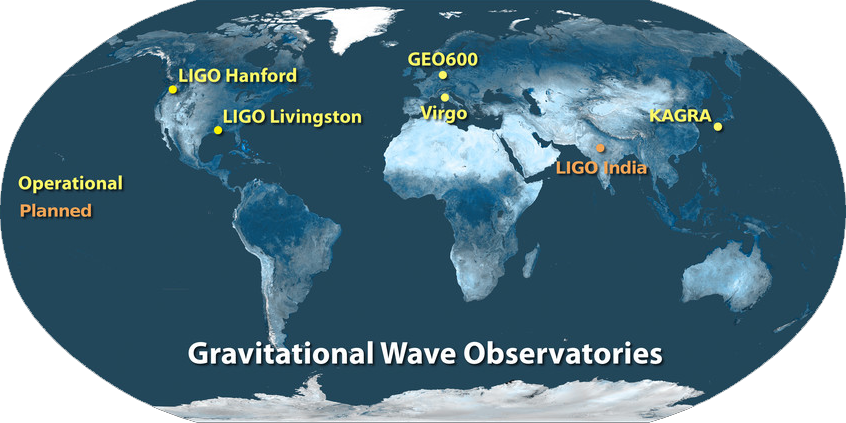

There are two LIGO detectors in the US - one in Livingston, Louisiana, and the other in Hanford, Washington. These two detectors are placed far apart, almost diagonally across the country, to maximize the distance between them. While they can detect gravitational wave events, having only two detectors makes it difficult to accurately pinpoint the exact location of the source in the sky.

Localization - finding exactly where the gravitational wave is coming from - is very important because it allows other telescopes to follow up and observe the event in different wavelengths, like visible light or X-rays.

That’s why we need a third LIGO detector, and that one will be in India - it will be called LIGO India. The detector will be built by the Government of India, while many crucial components will be supplied from the US. Originally, there were supposed to be three detectors in the US, with two co-located at Hanford, but that idea was dropped because co-located detectors tend to have correlated noise, which reduces their effectiveness.

LIGO India is a major project funded by the Indian government, through the Department of Atomic Energy and the Department of Science and Technology, with a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the National Science Foundation (NSF), USA. The project budget is around 2600 crore rupees. The Indian detector will work as part of the global network of detectors along with the two LIGOs in the US, the Virgo detector in Italy, and potentially KAGRA in Japan.

SS: Is KAGRA not operational right now?

SM: It is operational but at very low sensitivity, so its data is not very useful for astronomy at this stage. Both LIGO and Virgo detectors have 3-kilometer arms, while KAGRA is underground and also has 3-kilometer arms. Virgo’s sensitivity is roughly one-fourth that of LIGO’s, but it still contributes usefully. KAGRA’s current sensitivity is only about 1% of LIGO’s, so it’s still developing.

SS: Why do we need so many detectors?

SM: To localize gravitational wave sources on the sky, you need at least three detectors. With three or more detectors, you can triangulate the position of the source much more accurately.

Accurate localization is crucial because the electromagnetic telescopes that follow up these events usually have very small fields of view. If the localization region is large, by the time they scan the entire area, the signal might have faded.

In fact, the goal is to catch these events beforehand - early in the inspiral phase of the binary system. Here’s how it works:

Two compact objects - like black holes or neutron stars - orbit each other and emit gravitational waves, which carry away energy. As they lose energy, they spiral closer together, and their orbital period decreases. This means the frequency of the gravitational waves goes up, causing them to emit waves even faster. It’s an avalanche process leading to a final violent merger that we can detect.

SS: So, the more the two objects come together, they emit gravitational waves at an even faster rate? The more they emit, the periodicity goes up?

SM: Yes, exactly. The frequency goes up as they spiral closer, and they emit gravitational waves more rapidly. It’s like a nonlinear collapse process. Even before the two objects actually merge or touch, if the detectors are sensitive enough, we can detect them early and predict that something is going to happen within seconds or maybe a few minutes - at least about a minute before.

If we can detect the signal a minute beforehand, then electromagnetic telescopes can point to the right spot in the sky in time to catch the event.

For example, in a black hole–neutron star merger, the neutron star can get tidally disrupted by the black hole just before merging. If we have early warning, telescopes can capture this tidal disruption event.

There was an event called GW170817 in August 2017. After the merger, telescopes pointed there and observed it for months. We know what happens after the merger, but tidal effects before merging - which could tell us a lot about neutron stars - haven’t been observed clearly yet.

SS: So, in layman’s terms or in a bit of a fantasy way, the gravitational waves are like a prequel or a trailer, and the telescopes see the sequel - the electromagnetic signals after the event?

SM: Yes, that’s a good way to put it. LIGO India coming online will help us localize the source well enough to tell telescopes where to look.

If the sky localization isn’t accurate, telescopes don’t know where to point, so good localization is crucial.

SS: Why do we need three detectors exactly?

SM: It’s like GPS satellites. With two detectors, you can only narrow the source down to a ring or a band in the sky. To pinpoint the exact location, you need at least three detectors - three intersecting circles give you a precise spot.

SS: So with LIGO, plus LIGO India, we’ll have three detectors, and their combined data will allow us to pinpoint the source?

SM: Each pair of detectors gives you one constraint - essentially a circle (or more accurately, a ring) on the sky where the source could be. This is based on the time delay between when the signal reaches each detector.

For example, if the time delay between two detectors is zero, the source must lie in the plane that bisects the line joining the two detectors.

If one detector receives the signal a millisecond earlier, then the source must be in a location that creates a path difference corresponding to that millisecond. This helps narrow down the source direction.

When you combine this timing information from multiple pairs of detectors, a method called triangulation, you can localize the source much more precisely.

SS: So LIGO is already doing this. Then what’s the role of VIRGO and KAGRA?

SM: Good question. The key point is: for triangulation to work well, you need at least three detectors taking good data at the same time.

However, gravitational wave detectors like LIGO, VIRGO, or KAGRA are not always collecting usable data. Even when operational, they give useful data only about 70–80% of the time. Let’s take 70% for calculation.

So, the probability that three specific detectors (say, Livingston, Hanford, and VIRGO) are all operating and giving usable data at the same time is:

0.7 × 0.7 × 0.7 = 0.343 or 34.3%

SS: So, each detector has about a 70% uptime, and for three together, it’s about 0.7 cubed?

SM: Yes, exactly. But if we now ask: what’s the probability that at least three detectors are collecting data when you have four detectors available, the math becomes a bit more involved. But that probability turns out to be about 65% - almost double.

So, with more detectors, not only does your uptime for triangulation go up, your sky localization improves drastically too.

Currently, we have three main baselines: LIGO Livingston, LIGO Hanford and LIGO Louisiana. When LIGO India comes online, it will form new baselines: LIGO India - Livingston, LIGO India - Hanford and LIGO India - Louisiana. So, the total number of independent baselines increases from 3 to 6. Of course, change the name of the places (laughs!)

Moreover, the average length of these new baselines (especially with LIGO India, which is geographically farther apart) is about 1.5 times longer than the existing ones. Longer baselines give better angular resolution, meaning more precise localization of the source on the sky.

So, LIGO India won’t just be an extra detector - it will significantly boost both the accuracy and reliability of global gravitational wave detection.

SM: More detectors not only improve sky localization, but also increase the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). That’s why adding more detectors is essential.

Now, there’s another interesting point:

VIRGO and KAGRA use different technologies, developed independently. KAGRA, in particular, is quite different. However, they haven’t yet matched LIGO’s sensitivity, and may not reach that level soon.

LIGO-India, on the other hand, will use the same technology as LIGO (US). So, it’s expected to achieve comparable sensitivity. And since the site in Maharashtra is one of the best in the world, LIGO-India could become the most sensitive detector globally. That’s very exciting.

SS: How do you decide what makes a site “best”? These events are far away in space. Does location - like Moscow or Sri Lanka - really matter?

SM: Astrophysically, it doesn’t matter where you are. But for the detector’s functioning, it absolutely does.

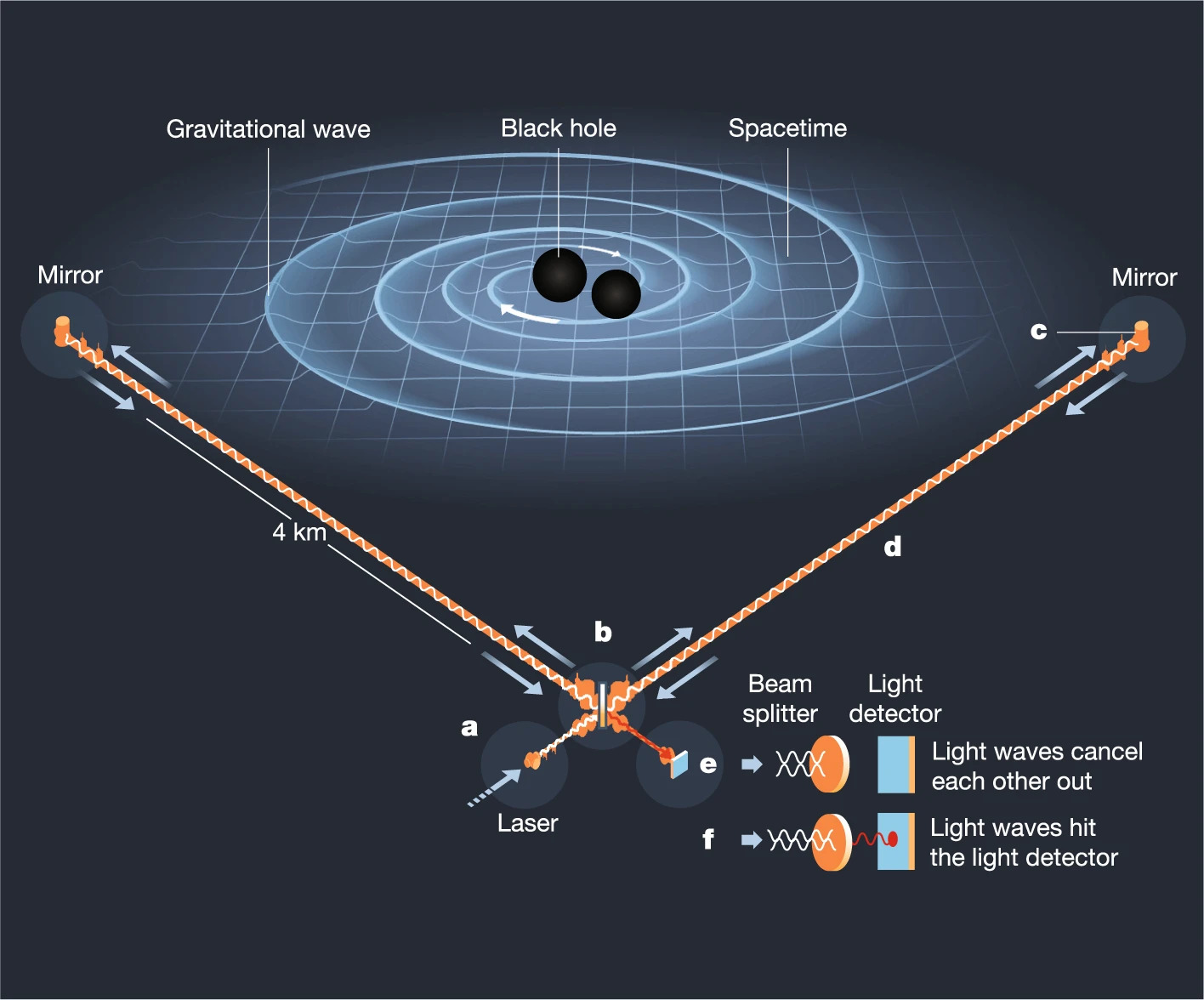

Gravitational waves are detected by measuring changes in the distance between two mirrors 4 km apart, using laser interferometry - down to one-thousandth the size of a proton.

That’s incredibly precise, so seismic noise and local disturbances must be minimal. While multi-stage suspension systems reduce this noise, if the site itself has high inherent noise, it limits sensitivity. That’s why site selection is critical.

SS: Inherent noise means?

SM: It refers to ground noise - mainly anthropogenic (like traffic) and non-stationary (varying over time). If this noise is high or fluctuates too much, it becomes hard to operate the detector.

SS: So it’s like putting a paper on a table - if the table shakes, the paper shakes too.

SM: Exactly. Or think of mirrors hanging like a pendulum. If you move your hand holding the rope, the stone swings. Similarly, if the detector base shakes, the mirrors move. That’s why detectors must be far from cities - daytime noise from cars is higher than nighttime. These things affect sensitivity.

SS: So we need a location that’s calm - anthropogenically, geographically, and geologically.

SM: Right. Geologically, you want low ambient seismic noise - not near the sea, because even sea waves create ground vibrations.

SS: So not in the Himalayas either - they’re geologically active.

SM: Yes, the Himalayas are too seismically active. While occasional earthquakes are manageable (the detector can be reset), in regions with frequent or strong earthquakes, there’s a real risk of permanent damage. So those sites are avoided.

SS: So, the Himalayas aren’t really an option?

SM: Yes, placing the detector there would be very difficult and risky due to the high seismic activity.

SS: And since major rivers originate there, the entire Ganga–Brahmaputra basin should also be avoided?

SM: Exactly. That region has been avoided. Instead, we focused on the Deccan Plateau, which is geologically more stable. Several sites were surveyed there, as well as in places like Rajasthan.

SS: So it’s not just astrophysicists working on this project.

SM: Exactly. Site selection isn’t based only on astrophysical considerations. For the science part, it doesn’t really matter where in India the detector is, but it has to be quiet, geologically stable, far from airports and highways, but not too remote - since scientists and engineers need to travel and work there regularly.

SS: Nissim sir also mentioned that some detectors are placed in deserts, which is good for isolation, but maintaining them becomes expensive and difficult.

SM: Right. Science needs people, and humans have to operate and maintain these detectors. That’s a practical constraint - we can’t go too remote.

SS: But what if the area around Hingoli becomes populated in 20–25 years? Cities might develop.

SM: That’s a real concern. It happened with observatories like IUCAA’s Girawali, where the sky used to be dark, but after 20 years, there’s now significant light pollution. GMRT also faced issues from mobile towers. For LIGO-India, we’ve taken some protective measures - there are agreements in place to prevent heavy industrial activity nearby, at least for the near future. We’ll try our best to preserve the environment around the site as long as possible.

SS: How do detectors work?

SM: The LIGO detectors are essentially very sophisticated Michelson interferometers. Each has two perpendicular arms with mirrors at the ends and a beam splitter at the intersection. A laser beam is split into the two arms, reflects off the mirrors, and recombines to detect interference caused by passing gravitational waves.

Now, in basic labs, you may have worked with small Michelson interferometers. For LIGO, we need to detect gravitational waves with wavelengths on the order of 1,000 km, but obviously, we can’t build arms that long. The actual arms are 4 km each, but we increase the effective path length using Fabry-Pérot cavities - by placing additional mirrors near the beam splitter, the laser light bounces back and forth roughly 300 times. This increases the effective arm length to about 1,000 km.

However, even with so many bounces, leading to orders of magnitude increase in laser power, shot noise becomes a major issue. It’s like trying to take a clear photo in the dark - you need more light. To combat this, LIGO uses a continuous-wave laser, currently at 70 watts, scalable up to 125 watts. This is among the most powerful continuous-wave lasers ever built. Note that while higher-powered pulsed lasers exist, continuous-wave lasers of this strength are rare and essential for LIGO’s precision.

SS: How can students like me - or future students - contribute to the LIGO project? And how can we benefit academically from being involved in such a large-scale experiment?

SM: LIGO-India is a mega-science project, and it’s inherently multidisciplinary. Almost every topic in a physics curriculum connects to LIGO in some way - gravitational waves tie into classical mechanics, quantum optics, relativity, statistical physics, and even thermodynamics. You’d be hard-pressed to find a concept in physics that isn’t somehow relevant.

The same goes for engineering: mechanical, electronics, computer science - all are deeply involved. For instance, the thin-film coating on the LIGO mirrors remains an active area of research. Even chemistry plays a role - in cleaning and maintaining the optics, understanding materials, or mirror surface interactions. And while biology might seem unrelated, there was a case (though anecdotal) where bacterial corrosion was suspected in vacuum tubes, requiring biological expertise to mitigate the issue.

So yes, while some disciplines are more involved than others - like physics, engineering, and mathematics - others like chemistry, and occasionally biology, also find surprising relevance.

SS: So, to summarize: physicists, engineers, chemists, maybe even biologists - all can find a place to contribute to LIGO.

SM: Exactly. It’s a collaborative ecosystem, with varying levels of involvement depending on the field. But if you’re curious and open to interdisciplinary learning, there’s a role for you.

SS: To shift gears a bit - how do you feel the Indian education system has changed over the years?

SM: Frankly, I expected much more progress in our education system. Over the last 20 years, I thought we’d be significantly ahead, but I don’t see major improvements. In fact, in some ways, we may have even regressed.

SS: Regressed? As in fallen behind?

SM: Possibly. It’s difficult to measure education precisely, but any nation that invests thoughtfully in education and science sees long-term returns. The real aim of education should be to teach students how to think, not just how to solve standard problems or memorize facts.

SS: So you feel we’ve not made progress in nurturing that kind of independent thinking?

SM: Exactly. What I see instead is students overwhelmed by constant assignments and evaluations, leaving little time for genuine thinking or exploration. Yes, continuous assessment keeps students engaged, but what does “progress” really mean? Just solving problems set by a teacher?

SS: Assignments, exams - that’s how we define success today.

SM: And that’s precisely the problem. Real progress is when students feel intrinsically motivated to learn, explore beyond the syllabus, and think independently. That’s how researchers are shaped - not by simply following instructions.

SS: So where do you think we’ve gone wrong?

SM: One issue is the shift from older systems. When I was a student, we had annual exams. We had the whole year to learn in our own way, and only one exam at the end. Sure, some students didn’t study and struggled, but even forcing them to study all year wouldn’t have made much difference if the drive wasn’t there.

SS: But isn’t that risky - like a one-day match? What if someone just has a bad day?

SM: True, but the deeper question is - why are we evaluating, and what are we evaluating? Evaluation should help growth, not dominate the learning process.

Today’s system robs students of time for creative exploration. When I was a student, I could spend time reading from different books, trying things my way. That’s missing now.

SS: So the older system actually helped you grow?

SM: Yes, definitely. It wasn’t perfect - it had loopholes. But instead of improving it, we’ve completely replaced it. Now, students follow instructions from multiple teachers across subjects. But how do we know all of them are teaching in the best way? Even I wouldn’t claim my method is perfect. If we rely solely on teachers’ methods and instructions, we’re placing enormous trust in individuals. Without space for alternative approaches or exploration, we limit the very essence of education.

SS: So can’t we just establish certain standard books - those that are locally or globally accepted? For optics, many trust Ajay Ghatak’s book.

SM: Sure, but if everyone blindly trusted one book, there would never be new ones. Even Ghatak must have learned from older texts. If he had just trusted those, we wouldn’t have his book today. That’s the issue - we often say “this is the book to follow” simply because it’s convenient. But true learning comes from comparing, questioning, and exploring beyond just one source. There may be a better book which you would be able to write and this is how things will progress because we are showing extreme faith in everything we have right now.

SS: If you had the power to reform the Indian education system, what changes would you make?

SM: Reforming the entire system isn’t something one person can do. But in my small way, I try to provoke students to think rather than overload them with assignments. I don’t believe in constant performance monitoring through regular assessments. Maybe two or three exams in a year are enough. If a student isn’t interested, it’s better they disengage early - academics should be for those who truly enjoy learning. Forcing uninterested students benefits no one.

See, we need to trust students. They’re adults - over 18. If they’re genuinely curious, they’ll come to class not to be spoon-fed, but to learn how to approach problems. A good student learns how to learn.

A good teacher creates independent learners. The best students are those who can learn on their own. The goal is not to create followers, but empowered thinkers. Ask yourself: what’s more valuable - a good teacher or a good student? It’s the student. A good teacher’s success is in creating good students.

SS: So, tell me, what is more important ? A good teacher or a good student ? Getting analogy from the Mahabharata, who is more important - Dronacharya or Arjun?

SM: It’s about resonance. Arjun had potential, but a different teacher might not have brought it out. Good students don’t appear on their own. Good teachers help shape them - but the goal is still to make the student shine, not just obey.

SS: In that context, what do you think of the National Education Policy (NEP)?

SM: I haven’t studied it deeply, but some of the ideas - like flexibility in subject choices and the credit bank - are good in theory. However, if not implemented properly, it can be problematic. For instance, many colleges already struggle with the 3-year BSc structure. Extending it to 4 years without proper infrastructure could make things worse. People might assume a 4-year degree is inherently better, but in reality, the quality could deteriorate.

SS: Why do you think students today tend to lean more toward technical fields rather than pure science?

SM: I don’t think that’s new. Even when I chose science, people questioned why I wasn’t going into engineering. Pursuing science requires a certain level of economic security. If someone is worried about basic needs, they’ll naturally prioritize jobs and income. That said, our research institutes still attract many strong PhD students. I just wish there were more.

SS: Do you believe in the “brain drain” theory?

SM: Not really. If someone wants to go abroad, let them. Sometimes, it makes sense to go where the best research is happening. But I often feel people go with the assumption that foreign research is automatically better. If they stay back, they may feel they’re missing out - and that lack of commitment can impact their work. You achieve the best results when you’re fully invested in what you’re doing.

SS: Suppose your current resources were reduced due to policy changes or external factors. Would you still be able to achieve your research goals?

SM: It would certainly affect the outcomes. Reduced resources mean reduced capacity. Some impact is inevitable.

SS: But when another country calls you, and you’re offered an opportunity - maybe not significantly better, but comparable - you tend to go. Let’s not talk about big names like the US, UK, or Russia. Even a smaller country can sometimes provide the support you need. Especially if you’re working on experiments or need high computing power, and those resources aren’t available here - then yes, it makes sense to go. And that’s where the idea of brain drain becomes relevant. You wanted to stay, you contributed here, like to LIGO-India, but when resources start drying up, naturally you start looking elsewhere. Say you’re contributing to LIGO-India, and a month from now, your resources are slowly getting cut off - yet you still get some support. But suppose another country - say, the Philippines - offers you better support. Even if it’s not a “lucrative” destination by general standards, you might consider moving.

SM: To be honest, it’s hard for me to answer this objectively. I’m part of LIGO-India, and that’s been a fantastic move by the government. Had India missed this opportunity and the third detector gone to another country, it would’ve been a disaster for us. People like me might still have chosen to stay in India, because I’m comfortable here and I like it. But I would’ve been disappointed. Some people love science more than the country, convenience, or community. That’s not a bad thing - science progresses because of people like that. They go where the science takes them, and maybe that’s how it should be. If I’m not doing that, maybe I’m the one in the wrong.

For example, if you’re doing gravitational wave research in India - especially theory, data analysis, or detector characterization - I don’t think you’ll find a significantly better environment anywhere else. Sure, there are experts across the world, but in India, we have a unique structure.

COLBREAK

The LIGO-India Scientific Collaboration (LISC) is one of the largest in the world right now. We meet weekly online. Any problem you have - someone will solve it. The group has more than 100 people, with very diverse backgrounds. You’d be hard-pressed to find such a diverse, supportive, and active group elsewhere. And we have full academic freedom. There’s no pressure to work on a fixed problem. Funding is secured for five years. Where else do you get that kind of flexibility?

Of course, government policies - whether from the present or previous administrations - do affect scholarships and funding. These cuts have real consequences. Every year, we see basic statistics showing our research output is declining. It’s not that every country is doing better, but we certainly shouldn’t be slipping. China, for example, is pouring enormous funds into research - there’s no comparison. They’ll do very well. But in gravitational waves, India still has enormous expertise. This is a great place to be - at least for now. Funding cuts will definitely impact instrumentation. Fortunately, LIGO- India is already funded, so we’re not seeing that impact directly yet. But if future instruments aren’t funded properly, it will hurt.

COLBREAK

SS: Do you regret not following the other path?

SM: No. What scares me is what would have happened if I had succeeded in those earlier exams. I would’ve likely taken a completely different route. Maybe that would’ve been the wrong

one.

SS: Or maybe not. Maybe you’d have loved that path too?

SM: Maybe. It could be that my personality is such that I’d have liked whatever I ended up doing. But I still feel I’m in an optimally placed position now. Whatever happened, happened for the best. Then again, if something else had happened, maybe I’d be saying the same thing about that path too. We’ll never know.

SS: Finally, any advice to my friends?

SM: You know, like you asked earlier about how I came into gravitational waves - it was never a straight path. I was determined to do something, and then something else came along that I

liked more, and I took that instead. I thought, “Oh, this seems better.” And this is my advice. Just do what you like.

SS: Thank you, sir.