Through The Eyes Of The Founding Director: Interview with Prof. Dattagupta

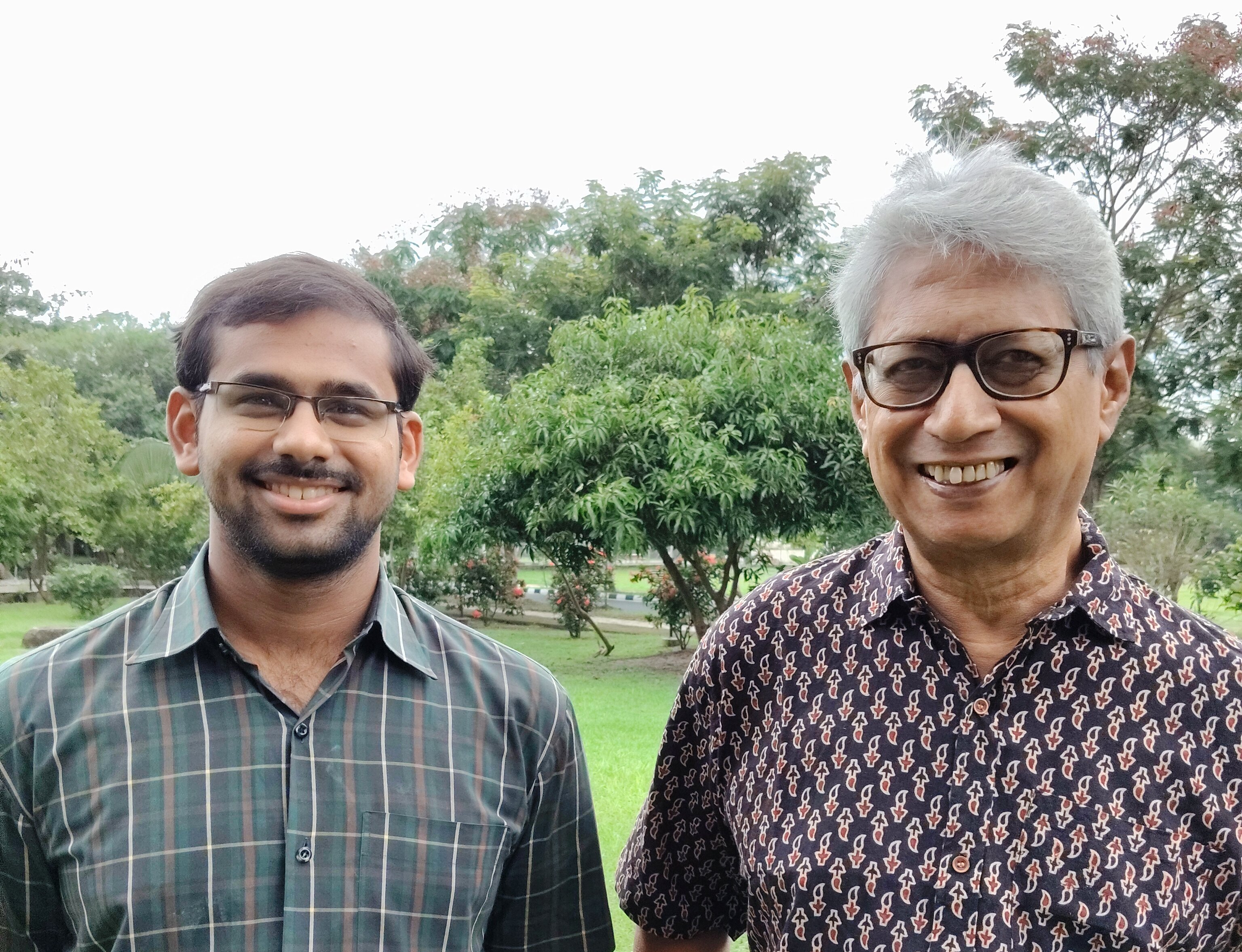

SS: Hello, sir. I am Swarnendu Saha from Team InScight and a BSMS student here. I welcome you to this interview session with InScight.

SDG: Thank you, Swarnendu.

SS:You were the founding director of IISER Kolkata and remain closely associated with it. Now, almost 16 years later, how do you see IISER Kolkata today? Has it stayed true to the original vision, or has the direction changed?

SDG:Thank you for having me. First, it’s actually been 19 years - we started in July 2006. At that time, IISER Pune and IISER Kolkata were the first two IISERs. Pune had the advantage of being adjacent to NCL, which provided access to facilities like water, power, and even lab space, including for NMR. We, however, started with nothing. The government channeled our initial funding through IIT Kharagpur, which gave us space in its Salt Lake campus. That’s where we began in July 2006. I was the only faculty member, and there was just one attendant - Ajay, who is still here.

To start teaching, we borrowed faculty from institutions like Calcutta University, Jadavpur University, IIT Kharagpur, Bose Institute, SN Bose Centre, and others. Recruitment had to begin from scratch. Once faculty were hired, we needed lab space, which we got at NITTTR Kolkata. So, between Salt Lake (IIT Kharagpur), and NITTTR, we began to grow. We also received faculty housing from NITTTR. By then, we had about 20–30 faculty members.

SS: Prof. Tapas Kumar Sengupta was among them, right?

SDG: Yes, in biology. In chemistry, we had Balaram Mukhopadhyay, Swadhin Mandal, Sanjio S. Zade. They were among the first recruits. In physics, we had mostly theorists at first; experimentalists joined later. In earth sciences, there were Somnath Dasgupta and Nibir Mondal, who had a lab at IIT Kharagpur. NITTTR provided some labs, but we needed our own campus. At that point, we approached the Ministry and the then Chief Minister, Shri Buddhadeb Bhattacharya. He said land in areas like Rajarhat or Newtown would cost around ₹20 crores per acre, with only 20 acres available - adding up to ₹400 crores, nearly all of our initial ₹500 crore seed funding (which increased soon after). It was financially not viable.

But I also believed in the historical precedent of institutions starting modestly - like IIT Kharagpur, which began in Hijli Jail, or IIT Kanpur, which dealt with dacoity issues early on. Great institutes don’t need to be in cities; they can grow in rural settings too. Fortunately, through the Chief Minister’s intervention, we received nearly 210 acres of land at Mohanpur for just one rupee - essentially free. But then, we were still grappling, because while the space was given, construction had to be done. And you might know that this area is very fertile, also it’s very soft land, because the river was very close.

Then the river moved away a little bit towards Hongsheshwari Mandir and all that. So, because of the softness of the land, you know, we had to do the foundation and all that. We had a wall, but then we needed some building space. We wanted to move, because by that time, faculty recruitment had started. We ordered two NMR facilities, 400 megahertz and 500 megahertz, x-ray, basic rudimentary things for physics and chemistry experiments, and a small animal house for biology. So, we decided to shift. We shifted here, I think, on the National Science Day, which is 28 February of 2009. We had then Governor Gopalakrishna Gandhi come and inaugurate the Raman Building. We basically got, through the West Bengal government, some old dilapidated buildings, which are adjacent to this campus that we are in now, which are in what is called the old Haringhata area, adjacent to Vidhan Chandra Krishi Vidyalaya and the University of Animal and Fishery Sciences.

And so, we reconstructed those buildings, like one building became the AJC Bose building. Those buildings were already there but in rather dilapidated condition. They were basically just left there, lying there as parts of either Bidhan Chandra Krishi Vidyalaya or Animal and Fishery Sciences under the West Bengal government. And there were also many hostel buildings, we renovated all of them. The new hostel building was called APC Ray Hostel Building. Another new building was called JC Bose Building, which is very scenic, next to the canal. And we even had a hut there, where we could congregate after every seminar for tea.

So, it gave an impression of almost like Cambridge actually. This is a very, very green campus. So, what I was going to say earlier was this, because of the fertility of the land, this area is very green and you throw anything, it grows, you know. So, I’m just making a preamble to coming to the campus now. The JC Bose Building, the Raman Building, you know, had absorbed many experimental facilities. Like in the ground floor, we had the two NMR machines looked after by Swadhin Mandal. He had some glove boxes and also inorganic chemistry facilities. Balaram Mukhopadhyay had his lab on organic chemistry. Chiranjib Mitra had his PPMS (physical property measurement system) and MPMS (magnetic property measurement system) and also the other measurement system.

Bipul Pal had also, you know, an optical table and all that. So, the ground floor of the Raman Building was occupied like that. Soon, we started accommodating some environmental biology people there. And then the lady who shifted later on, moved to Bose Institute, Srimanti Sarkar. Then we moved to the first floor and other people also had labs there. So, most of the chemistry physics laboratories were there in the Raman Building. And then in the JC Bose Building, we started to have some labs on the ground floor. Prashant Upadhyay joined.

And then next to the JC Bose Building was the LEL Building, the old LEL. These names are all from the animal and fishery sciences or BCKV. We again reconstructed, remodeled it. And we started a new experiment of having some eight biology faculty members in the same area, sharing their common research facilities, like Jayasree Das Sarma, like Partho Protim Roy, like Shankar Maiti, like Chanchal Dasgupta, like Tapas Kumar Sengupta and so on. Then the theoretical physicists had their offices there. So, we soon became almost 50-60 faculty members.

But this campus was still being built. Now, as I said, this is already 2009. We have already spent three years of our time. And then in this campus area, there were a few buildings left over. They didn’t demolish them. We also didn’t want to demolish them. We reconstructed them. And now you can see them. Just behind the guest house is the Polymer Research Center. Priyadarshi is there and Raja Shanmugam is there. And then there’s an Advanced Materials Laboratory, which is next door in the corner. Earlier, Sayan Bhattacharya was there, but he has moved out, I think. But then Soumyajit is there.

And then we created a seismic observatory towards gate number seven under Supriyo Mitra. It’s still there. There’s the equipment to check, because this is also an earthquake zone. And we wanted to connect to the Bakreswar Helium facility here. Because there’s a correlation between earthquakes and the proliferation of Helium in Bakreswar.So, we want to study that. It’s an inter-institutional program. And then there were two other buildings. One went to Radio Chemistry in Geology, Somnath Dasgupta and others, and the other to an environmental lab facility.

SS:Is this towards the Kalimandir?

SDG:Towards the Kalimandir, yes. So these five buildings were there. But then soon again, we were short of space. Architectural modeling was done on the campus. Your hostel buildings had started to come up, but we needed space for the faculty. So we created the prefabricated structure buildings. And your hospital facilities are there. Gautam Dev Mukherjee moved his high pressure laboratory there. Jayasree had her biology lab there. So things were moving and were increasing. I think by the time I left, it was in September 2011, we already had close to 80 faculty members.

And one thing I am very happy to tell you, that though by my narration, you would have got an understanding that we were working against many odds in terms of space, in terms of facilities, but let’s say we were very productive at that time, if you look at our publication record during that time. So, I state that concrete alone does not make good research. I mean, good research has to be done by the will of the people and the extent to which they put their mind to it and having very competent faculty. Most of them came after postdoctoral experiences, either abroad or in India, mostly abroad, after their doctoral thesis. And so, we had a very good set of faculty members. And J.C. Bose had two huge lecture hall auditoriums. I mean, each could hold at least 100 students. At that time, our intake was increasing. So, in the first year in the B.S.- M.S. program, the student intake was about 40, then it increased up to 100 maybe. And so, but then, as I said that the construction started and it was time for me to leave. Now you ask me, how do I feel after coming back? I feel very gratified.

I feel very happy that we chose this campus for one rupee, as I said. And it’s a beautiful campus. It’s very green, as you can see, with lots of trees, lots of flowers. And the swimming pool here, there are many sports facilities. And of course, the laboratory facilities are there. And so, facility wise, one cannot grumble, one cannot complain. It’s sort of very gratifying that we moved here, especially also, see, as I said, it’s less than 20 years. But maybe because the All-India Institute of Medical Sciences has come up, the roads have improved enormously. And by the end of 20 years, I think it will take you less than an hour to get here from the airport. So, if you compare, let’s say, with Indian Institute of Science, and the time of journey it takes from the airport to Indian Institute of Science, that’s actually much more than what it would be here in just about a year’s time after the Kalyani Expressway is built up. And if they can solve the National Highway 34 problem near the Amdanga area, then going to the airport will not take you more than an hour.

And the proximity of Kalyani University, which is a very good state university nearby, and then the WBUT, the West Bengal University of Technology just has got a new name now, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad University of Technology, which has come near the campus. Then Netaji Subhash University is supposed to come. And with the Old River Research Institute here, we had a kind of a hub of education, which was the original vision that I shared with Buddhadev Babu when we got land here. So, it’s very gratifying for me to come back and interact with students here and see how the campus has come up.

SS: After leaving IISER Kolkata, you’ve been associated with Visva-Bharati University. How would you describe the difference between the university system - particularly Visva-Bharati - and an institution like IISER Kolkata?

SDG: There’s a big difference. A university system like Visva-Bharati caters to all disciplines - not just science. In Visva-Bharati, the two most prominent departments are Kala Bhavana (Fine Arts) and Sangit Bhavana (Music). Another significant distinction is that Visva-Bharati integrates schooling into its system, a legacy from Rabindranath Tagore. It has pathshalas - like Ananda Pathshala, Santosh Pathshala, and schools like Patha Bhavana and Siksha Satra in Sriniketan. This integration of primary and secondary education within a university system is quite unique in India.

Furthermore, Visva-Bharati offers philosophy and comparative religion, various languages (including Chinese, Japanese, Arabic, Farsi, Indo-Tibetan Studies), and also runs a massive rural reconstruction program called Palli Sangathan in Sriniketan. There’s Siksha Bhavana for science, Vidya Bhavana for humanities, and Bhasha Bhavana for languages. By contrast, IISER is the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research - it’s purely focused on basic science education and research.

SS: And how do the IISERs compare with the IITs?

SDG: IISER is also very different from the IIT system, which primarily caters to engineering and applied sciences. Back then, we observed a trend - bright students were moving away from basic sciences, often opting for engineering through IITs or, later, NITs. Our aim with IISER was to retain scientific talent in India and in basic science, specifically. We wanted to make science education attractive and integrated, so that students didn’t feel the need to leave it behind after school.

SS: How did that influence the conception of the BS-MS program of the IISERs?

SDG: That’s a great question. You see, in our time, we had 11 years of schooling followed by 3 years of B.Sc., totaling 14 years before entering M.Sc. Higher secondary ended at class 11 back then. For your generation, it’s 12 years now. But here’s the issue: much of what was earlier taught in first-year B.Sc. got pushed into the last two years of school, syllabus-wise. But we didn’t have enough qualified teachers in the school system to handle advanced science topics effectively. So. what happened was repetition - the same things taught again in B.Sc., which affected depth. Now it’s 12 + 3, totaling 15 years, but content-wise it’s scattered and not necessarily deeper.

SS: So how did IISER resolve that?

SDG: We felt that the conventional 3-year B.Sc. plus the 2-year M.Sc. (3+2) model wasn’t ideal. Everything could be covered in 4 years, and we wanted students to experience research. So, we designed a 5-year Integrated B.Sc.-M.Sc. program, where the final year would be research-focused, like an M.Sc. by thesis. This also helped phase out the old M.Phil. system. By the end of five years, students like you would not only have had a robust science education but also gained research experience, maybe even a publication. From the third year onwards, we encouraged research projects - both within India and abroad.

SS: That must be quite different from a traditional university model.

SDG: Absolutely. Universities like Visva-Bharati follow a more segmented discipline structure, whereas IISER promotes interdisciplinary science from day one. In the first two years at IISER, students were taught all major science subjects - physics, chemistry, biology, mathematics, and even computer science and earth science. The idea was to broaden scientific thinking before specialization.

In fact, initially, we even considered admitting only those students who had studied mathematics in school, to ensure a stronger foundation across the sciences. Students without mathematics were not encouraged to join initially. I don’t know now what’s happening. But there were some students who never had biology. But there are instances here where a student after doing biology in the first two years had got shifted or drifted to biology.

SS:I actually know of two such instances. One of them is a member of InScight, she’s an alumnus now. She didn’t have biology in 11th and 12th and didn’t want to do it. She studied biology in the first two years because it was compulsory, but she ended up obtaining an MS in biology.

SDG:Ujani was in the first batch and she’s another example of that, had a PhD in biology from Cornell and she is now in the faculty somewhere in biology. So, here are instances of that also. I’m very happy about that kind of interdisciplinary approach that we could instill in the students there and you are now saying that that has continued which is a very gratifying thing which is one of the aims and objectives of IISER.

By the way, life science started as an interdisciplinary subject - we branched off into different departments unfortunately, but it is very interdisciplinary and especially these days, when focus is very much on biological systems and material systems, you need interdisciplinary approaches of mathematics, chemistry and physics. So that way we feel that IISER was a very good experiment. Anyway, Visva-Bharati is another model.

Even within the university system Visva-Bharati from the Tagorean idea is a very different kind of a model. It’s a unique model. I’ve already mentioned about the fact that the schools were part and parcel, the schools were imbibed within the university system. That’s very different from other central universities like let’s say JNU or Hyderabad University where I have served also. So that way, I hope I have answered your question about the difference between Visva-Bharati and IISER. Both are two different, both are very good experiences.

SS:Do you see yourself more as a scientist or as a teacher?

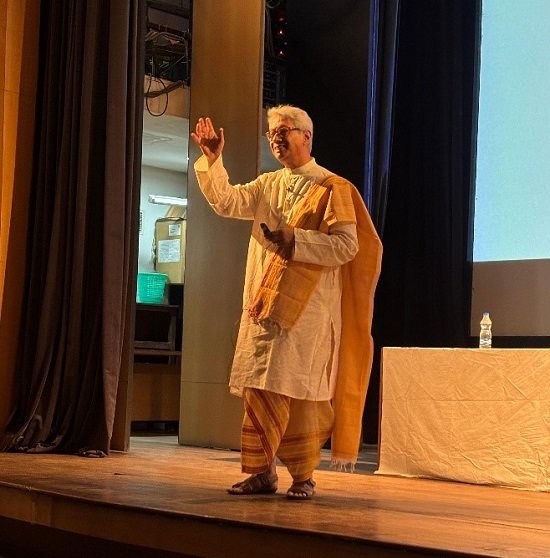

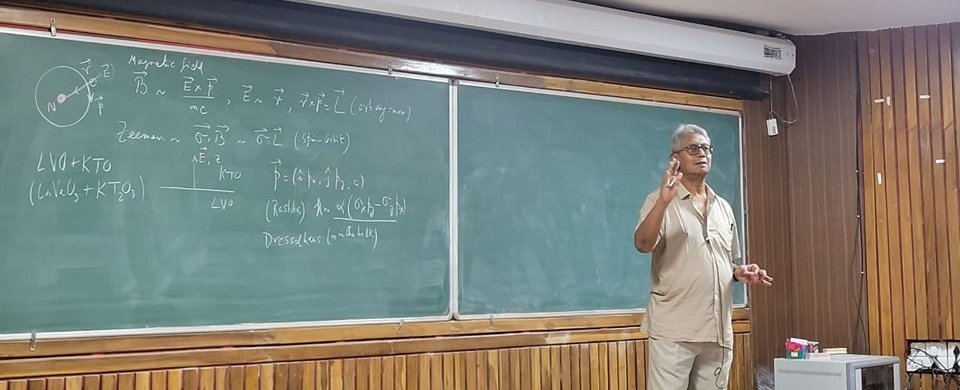

SDG:I would say teacher and a researcher, in that order. Because that’s what I enjoy doing - teaching with research. I think teaching and research are two sides of the same coin. One cannot do without the other and in fact through classroom activities you get many new ideas of research also.

I can give you many examples from the history of development of physics where such things have happened. Because research is something that lies within yourself and maybe with some collaboration with some other colleagues but when you teach, you interface with a large number of students, you make eye contact, you sit with them over tea and then discuss even outside classes. So that’s the part I enjoy most.

There can be, I believe in IISER also, there can be instances, there can be some people who are great teachers but research-wise they may not be the first options for the students. Similarly, there can be people who are doing fantastic research if you join them, it’s a different ballgame but in classrooms they might not be the best teachers chosen for. So, my philosophy is that you have to be both if you want to be in IISER. If you only want to do research and write papers then you can be in a research laboratory. There are many CSIR labs, DST labs etc. – Tata Institute, where you don’t have to do much teaching.

Your primary condition of even employment is that you’re here to train students through teaching. At the same time, you also have to do research. So, I think that if your focus is only on research then IISER is not your place. If your focus is only on teaching also and not writing anything or doing much research then you’re also a misfit here. So, you have to have a combination of both and this is the model I personally like very much. Even at this age I’m still productive in research. I write five to six papers a year in international journals. I even wrote some single author papers in the last three or four years in the physical review. Therefore, that part is there.

At the same time I feel that I must be able to translate my even physical review level research into a classroom teaching either for MSc students or even PhD students and even go to undergraduate level because that’s the hardest part to teach because when you come fresh from school and your mind is keen to get into new ideas, stir up the class with questions and so that is also something I enjoy very much.

SS: One of the goals of the IISER system was to retain bright minds in basic sciences. Can you comment on how studying basic science actually helps students in their career? Students like me who have obtained their BS-MS degree and want to pursue academia have to constantly worry about certain questions: What is the employment status after BS-MS? How about after a PhD? Some people say that basic science is saturated. Others say that while an engineer will always find employment, a student of science has to wait until they become a scientist in order to get a proper job - and even that is on God’s grace. What’s your opinion on this?

SDG: Okay, I appreciate the question. Let me say this first - You have to do what makes you happy, what brings you peace, and what makes you feel that you are your own person. You hold your own destiny in your hands. In a government system or industrial job, you might often be working to fulfill someone else’s vision, climbing hierarchies, fulfilling institutional mandates. But one of the main reasons many of us chose academia is because we value academic freedom. While I admit that this freedom is slowly eroding, it still exists. So, first - do what makes you happy, not what others expect of you.

Secondly, let me talk about the societal aspect. Recently, I was teaching as a guest teacher in a school in Durgapur. The students were bright, and I enjoyed the interaction. But soon they began opening up. They told me horror stories - from class 5 or 6 onwards, they are pushed into private tuitions and coaching classes. It’s quite traumatic. This is a new phenomenon, especially in townships like Durgapur, Jamshedpur, Rourkela. Parents are often part of nuclear families, and in the evenings, they have nothing else but to focus on but their children’s academic performance. It’s led to a system where coaching culture has become the new normal. Places like Kota have institutionalized this pressure.

This - what you’re describing - is not just about science vs. engineering. It’s about a deep-rooted societal insecurity: “What will my son or daughter do?”, “Will they earn enough?”, “Can they support us?”. And there’s a gender bias too - people often think, “My son will support the family; my daughter will get married.” These are toxic ideas, but they’re still very much present. So, if students fall victim to these insecurities, it’s a problem. And sadly, this insecurity is pervasive in middle-class India today.

SS: It is often said that it is easier to get a job in engineering that in science. What do you think of that?

SDG: Let me give you a counterexample. Take Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis, who started the Indian Statistical Institute (ISI). They run a B.Stat and M.Stat program that is phenomenal. If a student from ISI combines that with even basic business knowledge, they might end up earning more than an average IIT graduate. People just don’t know about these opportunities. Or take mathematics - people think there’s no future in it. But if you study math seriously, you can go into economics, data science, AI, finance, or modelling. You can enter banking, research, analytics, and so many other fields. So this idea that only engineering gives jobs is deeply flawed. There are plenty of opportunities in science - you just have to know how to navigate them.

Bottom line: this belief comes from middle-class insecurity, not from reality. That’s why, Swarnendu, the very fact that you’ve left home, stayed in a hostel, and are thinking independently is already a big step. Now is the time to free yourself from societal pressure and follow what you truly love.

SS: That is certainly encouraging, but the issue of funding remains, especially for those who are not yet in institutionalized research.

SDG:I agree that there are irritating issues. I believe that Bengal doesn’t have too many possibilities today and people want to leave, people find things elsewhere. Yet Bengalis, I know, don’t want to leave this state. The cultural bonds are so strong. So, there’s a dichotomy here and you’re caught in that.

I agree with that. But earlier, you know, we went abroad even for graduate school etc. leaving our family. They were crying and all that sort of thing. But having done that, you feel happy. The world is becoming smaller and there are many possibilities. So, think of those possibilities. Don’t feel that you have to be cocooned in Bengal, as a Bengali I’m saying.

And if you don’t have that feeling, then you will find that there are many possibilities. At the same time, it is possible that today’s climate is not really healthy for science. This is something that we don’t want to get into in this discussion in detail. This is my feeling But what can you do? It is not in your hand. You can, of course, have a certain hand that you have voting power. But other than that, you have very limited ability to change the system. But nobody else can change you.

SS: Do you believe in the brain drain concept?

SDG:I don’t believe in it because the world is one world. This did not happen in our time. Today there are a lot of students going to Korea, and a lot of students going to Singapore, Malaysia. This didn’t happen during our time. So there are possibilities elsewhere, right? Israel, well, of course, Israel is now at war. But I’m saying many students are going to Israel, Weizmann Institute and other places.

So that didn’t happen during our time. During our time, it was only the UK and America. Students are now going to Germany, France, and Russia. So I think things are changing also. So now brain drain, you’re talking about, possibly there is a brain drain outside, away from Bengal. But I’m hopeful that things will change.

SS:Well, the issue often is that people go elsewhere because there aren’t too many quality opportunities here. And very often, if such people become successful outside, they do not feel the need to come back to the country. It almost feels like had they had opportunities to become succesful here itself, it would be a gain for this country as well.

SDG:Yeah, one thing I feel is Swarnendu, I think institutes like this should also be international. There should be students not just from all parts of India but also from outside. This is the strength of the Western universities like Oxford, Cambridge or American universities. Vast number of students come from outside. So you also have a cultural mix. You should not be just soaked into one culture and so if you are very multidimensional, then maybe such concerns should be little less, what you are talking about.

SS:But in India, everyone who has to join higher education, masters or PhD in a good place, as far as science is concerned, you have to clear JEST or JGEEBILS, NET, GATE and those are the only pathways you can achieve that. In international universities, you can just mail them or apply in a portal and if there is a possibility, they reply back to you. That doesn’t happen in India.

SDG:So Swarnendu, if you ask me as a private person, I do not believe in all this NET, GET etc. You know that I served Visva-Bharati. Rabindranath Tagore didn’t go to school. Einstein didn’t have a very fantastic record in schooling. So, these are mechanical things. Perhaps they came in because they had to uniformize or whatever, a PhD from one state was not the same as a PhD from another state. Traditionally in Bengal, University of Calcutta, not in your time maybe, but in our time, they were very conservative about giving marks.

So even 65% in physics honours was considered to be very good, not today maybe, but that is not the case let’s say in another university which I’ll not name. So maybe they had to uniformize, but I don’t believe in these things. So, I think these are all mechanical things and really motivated students may be deterred from such mechanical things.

On a given day, you may not do well in a NET exam or GATE, but you are good. So why should the system lose you? So as a teacher, I would like to support such students, but as a system it’s very difficult. So, I agree with you that when you are writing to professors abroad, they don’t ask you whether you have cleared your NET, GATE and all that.

SS:They only take interviews if they have a position and they try to understand if I can do it. If not, I know it or not. If I am able to do it, I think that should be adequate. If the teacher wants it, you want the teacher, the place administrator wants you and it’s done.

SDG:Yes, yes and I think that’s the healthy system. We actually have got into an unhealthy system, very mechanical. I will give you an example.

Since you mentioned Visva-Bharati, have you heard of Ram Kinkar Baij? He was a sculptor. He’s from Bankura, completely supposedly illiterate. Could he have become a professor in Visva Bharati by today’s standards? He had not cleared NET. He used to stay in his own world, stay in his own fashion. He was a professor. Konika Bandyopadhyay was a professor. Did Konika Bandyopadhyay clear NET examination? So why do you have such things? J.C. Bose did not have to clear NET examination. By the way, they were all part of the teaching departments.

You were asking earlier about teaching and research. The fact that S. N. Bose could do this problem of how to count and have a new kind of statistics by saying that particles are indistinguishable, that happened because students were asking him, barraging him with questions. “Sir, this derivation of Planck law radiation is not very satisfactory, you know, you please explain.” That is what drove him there. To answer the question in the class.

It was not just in Dhaka in 1924 when he wrote that letter to Einstein, but it started happening from 1920-21 onwards in University of Calcutta when he was teaching mathematics here. So it is because of the students asking him questions. The researcher J.C. Bose was teaching in Presidency College. So, examples galore where teaching and research in combination have produced this.

Here, after independence, we have separated our research institutions from the university system. Has that been good for us? We keep on asking why there are no Nobel Prizes from here? The answer is obvious, I think.

SS:On to my next question. For the last several months, many international opportunities have become blocked. The US appears cutoff. UK says we don’t have funding. many countries are at war. In this scenario, what is your suggestion? How should today’s students make progress? Is doing a PhD in India a good choice? More specifically, how much of a difference does getting a degree from a good Western University make versus getting the degree from a good place in India?

SDG: Let me answer the last part first. There are many counterexamples of students, who have done PhDs in our country, have done exceedingly well internationally also. I can give you some names also. So, I think again that distinction is immaterial. The first part is difficult for me to answer. Let me tell you my own experience with my two daughters.

My elder daughter Shahana, after schooling, did architecture from Delhi School of Planning and Architecture. Then she had some higher degrees in the U.S. and also she was working for a company. So, as an architect, she would have done very well.

She is very, very creative. She is very strong in mathematics also. But today, she is completely into Dhrupad music. So, one may think, ah, she has wasted her career. She could have become a great architect, but she is in Dhrupad. I don’t think like that - she is personally very happy with music – she has innumerable mentees all over the world - and I am extremely happy for her.

My younger daughter Sharmishtha did chemistry from St. Stephen’s College, Delhi. And then did an M.Tech program from IIT Bombay in biotechnology. Then did a PhD in deep sea biology in Pennsylvania State University. Eventually had a position, faculty position, in geobiology in the Courant Center of Excellence in Geo-biology in Gottingen University. But she gave up everything and she is now a life’s coach.

What is that? Basically, she talks to people about happiness in life, going mountaineering, going to yoga, going to, you know, practising spiritualism and traditional knowledge, ecology and all that. And she lives mostly in India, in Himachal now. And also works with Adivasi women near Shantiniketan in Bolpur, where I stay.

SS:And that’s very fulfilling for you, I guess.

SDG:Fulfilling for her also. So, what more does one want in life, I am saying. She drives all the way in her Alto Maruti car, all the way from Himachal to Shantiniketan, Bolpur, where I stay in the house designed by Shahana, who is an architect. So, they are not in any kind of traditional mold anymore. This is very different from our days. Since you are asking me, it is a very difficult question to answer now.

Because in our days we came from middle class families - one track minded. You have to do physics, then you have to do this, do PhD, do post-doc, then see where you get the faculty position. So, these kids are now able to do many other things. So, Swarnendu, the reason it is difficult is that our days and your days are very different now. So, we should not bias you from our kinds of experiences. And we should also adapt to your needs.

The fact that you are happy with doing what you are doing is the most important. Gone are the days where you would stay at home, looking after parents in the old days, etc. But, you know, that also made parents dependent, your dependent, and your freedom curtailed. But now, even staying away, you can do a lot for your parents. I don’t think that that concern is not there anymore because connectivity has also increased, you know. You can travel much faster today compared to our days. First time I went inside a plane was when I went to the US for my PhD studies. But these days, you guys are travelling all the time.

SS:This question is not to the researcher Sushanta Dattagupta, but primarily to the teacher Sushanta Dattagupta and the person Sushanta Dattagupta. Do you feel today’s students have forgotten to talk, have forgotten the meaning of friendship. Today’s students, though more alert, frequently fall prey to substance abuse. After graduating, they forget the friends they made there. It feels like we talk only when we absolutely need to, and not for the sake of relationships. Even though many of my school friends are in Kolkata, we rarely meet. Do you have any comments on this trend?

SDG:I think this is not a good trend. In fact, when COVID happened, we went into a system of virtual classes. I think that’s disastrous. Unless you have eye contact with the teacher, and also reversely with the students by the teacher, it’s not a very effective communication. That’s number one. So, what you are saying is that today, most of the time, with earplugs, listening to mobile phones, maybe some music, some recording, you have very little time for even Adda, as you mentioned.

SS:We all have problems - academic problems, financial problems, problems at home, etc. But we don’t have close friends to talk to about them. It seems like people are insecure about opening up in front of others about their vulnerabilities. How does one cope with that?

SDG:I don’t really know. One thing is sports facilities. Like, you know, if you are feeling bored, go play basketball. Go play volleyball. Chat with the guys. This campus is fantastic for that. Go and have a swim. Do that. Or go cycling in the campus. Watch the birds. Watch the many varieties of flowers here, nature. Getting hooked on the mobile phone is a scourge, I think.

SS:How are Tagore’s works related to science?

SDG:Fantastic. A lot of people don’t know that Tagore was very interested in mathematics. His eldest brother more so.

SS: Are you talking about Dwijendranath?

SDG:Yes. He was very good at maths. And he was the one who was a nature lover. Birds and all that. So, he imbibed that. Tagore actually got a lot of things from his brothers and combined them into the genius that he was.

The first article that Rabindranath published in Tattvabodhini Patrika at the age of 12 was on astronomy. So, then, you know, Tagore is quite interesting. Tagore was a great friend of J.C. Bose. Around 1900, they were writing lots of letters. Bose Institute has come up with two volumes. In which these letters are there. But, if you look at them, Tagore was trying to understand what Bose was doing. And, Bose was actually propagating Tagore’s works in the western world also. Translating them into English.

So, science was very much in Tagore’s mind. Eventually, he went and met Einstein. Five times. Between 1926 and 1930. Then, Heisenberg came in 1929 to Jorasanko to have tea with him. He went to Darjeeling on the way. He stopped by and had tea with Tagore. And, he wanted to understand about Upanishad and the idea of how you learn things from nature. And, the fact that Upanishad, this is what he says to J.C. Bose. Upanishad taught us that everything, even which you think is immobile, actually vibrates with life. He basically talked about atoms and molecules, even in trees and even in concrete. And so, Heisenberg writes about that to his daughter. Then, Sommerfeld went to Shantiniketan in 1928.

It is Sommerfeld who during Tagore’s visit to Germany introduced Meghnad Saha to Tagore. Tagore talks about Meghnad Saha’s work in Bishwa Parichay, which he wrote between 1934 and 1937. Bishwa Parichay has various sections - full of various scientific concepts and much of it has to do with radiation and Alo (light). And what is the meaning of Alo? And Alo, as you know, is a basic aspect of science. So, Tagore, I think, had a scientific mind. It’s just that he is a great philosopher.

SS:It has been very nice talking to you, sir. One last question, what is your advice to the students, and maybe particularly to the outgoing students?

SDG:Be happy, be on your own and be responsible to your surroundings. Worry about the fact that we have done big damage to ecology in the name of development. If you look after your health and look after your health means that you have to do physical exercise and look after your diet and also be happy. So, mental peace is the most important thing in life and that is what you should have. And finally, as you said, and I’m unhappy to hear this, you must have a lot of friends and have a lot of Adda.

SS:Thank you, sir.