Cosmic music of the Sun: Rossby and other inertial modes

Did you know that the same kind of waves, which help shape Earth’s weather patterns, may also ripple through the Sun’s atmosphere? Rossby waves are a special class of inertial waves which are restored by the Coriolis force in a rotating body [1,2]. Rossby waves are particularly caused by a rotating sphere’s special property that the Coriolis force’s tangential component changes with latitude. They are a cornerstone in Earth’s climate science [3,4]. But what happens when we look for these waves on our star? Imagine the Sun as a musical instrument where waves resonate differently within its rotating plasma. Researchers only recently attempted to observe such inertial waves on the Sun [5]. Why do we care about these waves in the Sun? Because they help us understand how the Sun spins, how it ages, how the plasma inside the Sun behaves, and even how it influences space weather — all things that affect our life on Earth in ways we’re only beginning to understand! In this article, let us explore how we can observe the solar inertial modes and why they could not be identified in the Sun earlier. Then, we shall try to understand their importance for the Sun. Finally, we discuss the fundamental physics of these modes and the future of this field of research.

How do we observe solar inertial modes?

When the rotationally driven inertial waves are trapped inside a closed system like a spherical shell, they are called inertial modes. To understand why observing inertial modes on the Sun took so long, we must consider how they behave in rotating systems.

Inertial modes oscillate with periods set by the rotation rate of the system. Any inertial oscillations must have their frequency ranging from to for a system rotating at an angular frequency [2]. Now, consider the rotation rate of the Earth and the Sun. The Earth takes one day to complete one rotation, while the Sun takes about 27 days to complete a rotation. The period of inertial oscillations in the Sun will be much larger than in a fast-rotating body like the Earth. Hence, we need long-term, continuous observations of the flows on the solar surface to identify inertial oscillations in the Sun. This has been made possible with recent high-resolution observations of the space-based telescope Helioseismic and Magnetic Imager (HMI) from the Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), a spacecraft of NASA. First, the classical Rossby modes were identified using the Fourier transformation in longitude and time at each latitude of the solar surface flows obtained using this telescope [5]. The Fourier transformation in longitude fixes the azimuthal wavenumber m, which is the number of wavelengths around the equator for a mode. Then the first observations were combined with the observations of the Michelson Doppler Imager (MDI) from the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO), a spacecraft of the European Space Agency (ESA), using a technique called time-distance helioseismology [6].

Later, many other inertial modes were observed on the Sun using observations from HMI and the Global Oscillation Network Group (GONG) from the National Solar Observatory (NSO), headquartered in Boulder, USA [7]. Figure 1 shows the eigenmodes of the high-latitude inertial mode and the classical equatorial Rossby mode adapted from [7]. The high-latitude inertial mode with azimuthal wavenumber m = 1 has the highest power in the observations, and it was found to be driven by the temperature difference between the poles and the equator of the Sun due to the difference in the rotation rates [7,8]. This is termed baroclinic instability. The unstable high-latitude mode has recently been identified in daily-cadence solar Doppler Grams, including the ones from the Mount Wilson Observatory (MWO), at Los Angeles, USA, since 1967 [9]. Figure 1 compares the observed eigenmodes with the 2-dimensional eigenmode computations of [8]. Scientists have recently compiled a review on the observations and modelling of different classes of solar inertial modes [10], which can help one get a nice overview of the recent advances in this field of research.

Why are they important?

Rossby waves on the Earth are vital because they affect the weather patterns on the Earth. Why would they be interesting in the Sun, given that there are no clouds, rain or floods in the Sun? In contrast to the Earth, inertial modes in the Sun can reveal secrets about its hidden internal dynamics. Helioseismology using pressure modes can tell us a lot about the solar interior [11-12]. But pressure modes can’t tell us much about viscosity, heat flow, or temperature deviations in the interior of the Sun. These quantities are essential for global solar simulations as well as modelling and predicting the solar magnetic activity. In particular, there exists a disagreement between the velocity amplitudes in simulations and observations, termed the convective conundrum [13-15]. The inertial modes have been demonstrated to be sensitive to many different parameters, which are not well-constrained yet [7,8,16]. Thus, inertial modes can aid in the Sun’s diagnostics and help solve this conundrum.

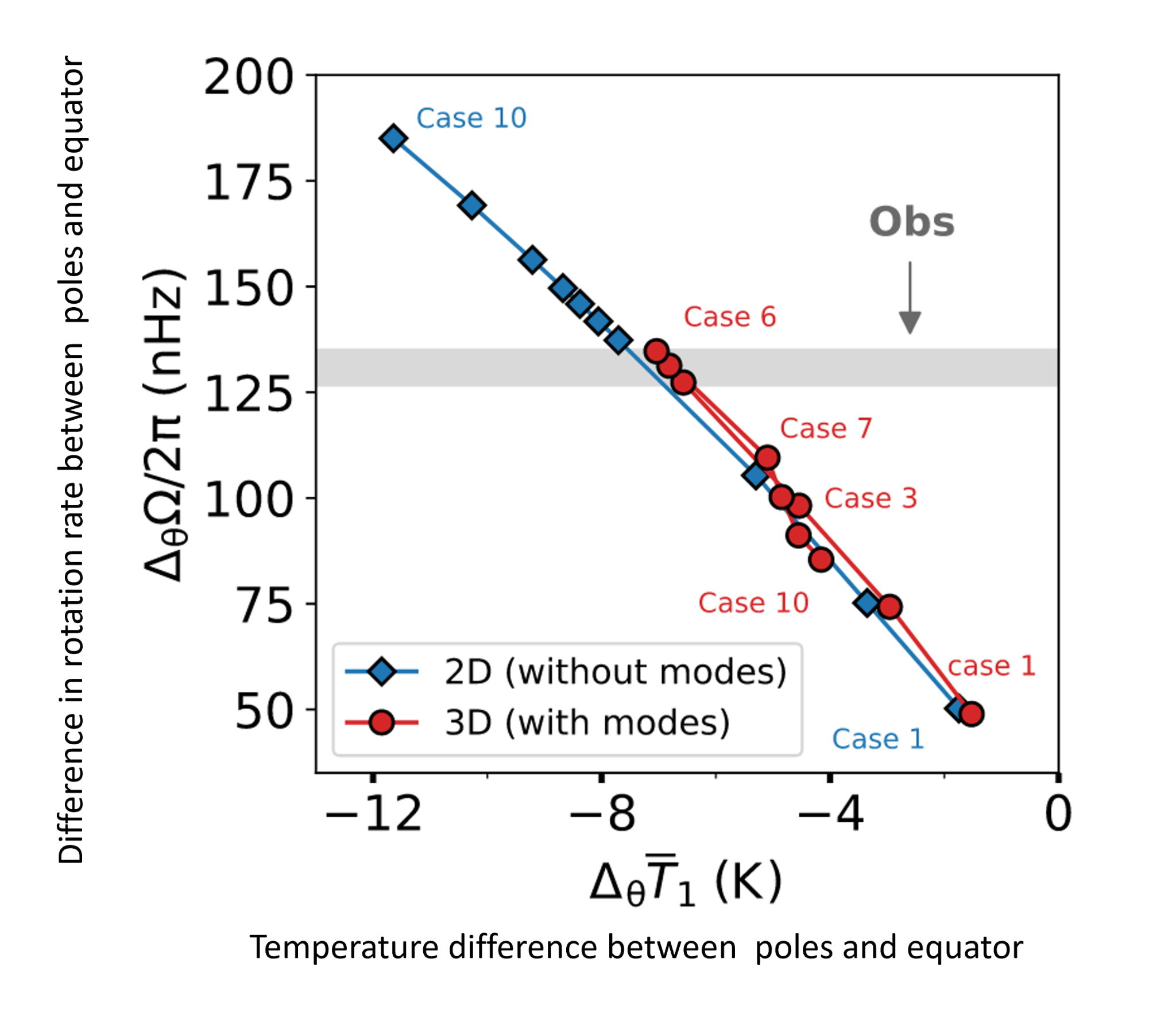

Furthermore, unstable high-latitude inertial modes have also been found to play a dynamic role in the Sun by controlling the solar differential rotation [17]. Figure 2 illustrates how these modes act like a feedback system, regulating the Sun’s rotational and temperature differences across latitudes. The different cases have different degrees of convective instability, increasing with the case numbers, as described in [17]. In the absence of these modes, the difference between the rotation rates and temperatures at the poles and the equator can become much larger compared to the cases with the modes. In the presence of the modes, the differences are limited to a specific value, close to the observed difference in the rotation rate between the pole and the equator.

Physics behind the inertial waves

For those interested in physics, here’s how scientists break it down mathematically, starting from the fundamental fluid dynamics. A fluid’s spinning or swirling motions can be quantified as a quantity called vorticity. Inertial modes can be described as waves of this quantity called vorticity [2]. Hence, analysing the vorticity budgets of the inertial modes is instrumental to understanding their physics, as done in [18]. Let us skim through this approach in simple words. Starting from the equation for the conservation of momentum of the fluid, we can obtain the equation for vorticity by taking a curl, which helps get the system’s spin from velocity. To analyse how the different physical effects determine the frequency of the modes, we transform the equation of vorticity 𝜻 (radial and z-components) to the following form, as shown recently [18].

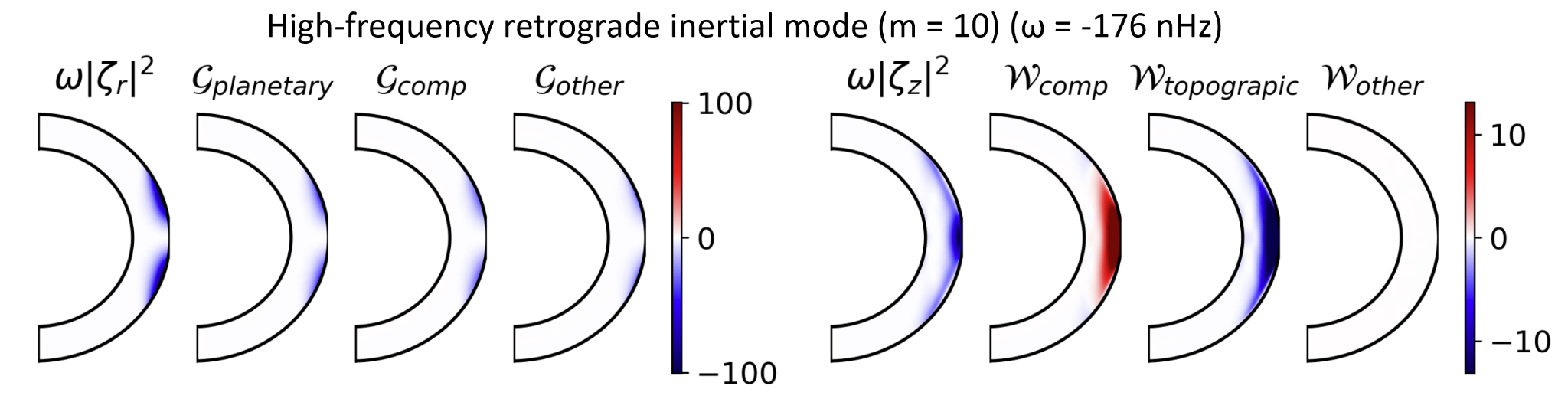

Here ω denotes the angular frequency of the mode studied. Here we decompose the vorticity equation into the different physical effects. The planetary β effect (denoted by planetary) is caused by the latitudinal variation of the tangential component of the Coriolis force [2]. It is the primary driver of the Rossby modes. The compressional β effect (denoted by comp) is caused by the change in background density when a fluid parcel moves along the radius [2]. It becomes essential only when there are radial motions associated with the mode. Finally, we also have the topographical β effect (denoted by topographic) caused by trapping the fluid parcels in a spherical shell [1]. The sign of the terms in the above equations associated with these physical quantities determines the direction of propagation of the modes. This is because the frequency is multiplied by the absolute value of the different vorticity components, which is always a positive real number. Figure 3 shows how the various physical effects determine the frequency of a mode by promoting their propagation either in the direction of rotation (prograde) or against the direction of rotation (retrograde). It shows the example of the high-frequency retrograde inertial mode discovered in [19]. This is an interesting mode driven by the combined effects of planetary β effect, compressional β effect and topographical β effect, as found recently [18]. The compressional β effect drives it prograde, while the other physical effects compete to drive the mode retrograde. Furthermore, the importance of compressional β effect due to the presence of radial motions in the inertial modes makes the inclusion of background density variations necessary while modelling the solar inertial modes, as found in [18]. This is in contrast to the inertial modes on the Earth, where the background density can be assumed to be constant because of slight variations. On the other hand, density drops off steeply with radius in the Sun.

What does the future hold?

There are many aspects of developments in the modelling of inertial modes. The inertial modes are sensitive to different physical quantities in the solar interior. It will be fascinating if the inertial modes can precisely reveal these yet unknown physical quantities to help the convective conundrum. Apart from that, how the inertial modes affect or are affected by solar magnetic fields is not well understood. Also, we do not yet know how the solar inertial modes are affected by different layers of the Sun, like the radiative zone and the solar atmosphere. Furthermore, how the unstable high-latitude modes saturate is to be understood carefully, as their amplitude can not grow indefinitely over time. Many of these topics are actively explored at research institutes across the globe. As we unravel the Sun’s hidden rhythms, we’re not just doing solar science — we’re playing catch-up with the universe’s cosmic symphony. The future promises more discoveries, and maybe we’ll soon predict solar storms even more accurately than we forecast monsoons.

References

- Pedlosky, J. 1982, Geophysical Fluid Dynamics (Heidelberg: Springer, Berlin)

- Vallis, G. K. 2017, Atmospheric and Oceanic Fluid Dynamics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

- Schubert, S., Wang, H., & Suarez, M. 2011, Journal of Climate, 24(18), 4773-4792

- Pinault, J. L. 2022, Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 10(4), 493

- Löptien, B., Gizon, L., Birch, A. C., et al. 2018, Nature Astronomy, 2, 568

- Liang, Z.-C., Gizon, L., Birch, A. C., & Duvall, T. L. 2019, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 626, A3

- Gizon, L., Cameron, R. H., Bekki, Y., et al. 2021, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 652, L6

- Bekki, Y., Cameron, R. H., & Gizon, L. 2022, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 662, A16

- Liang, Z.-C., & Gizon, L. 2025, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 695, A67

- Gizon, L., Bekki, Y., Birch, A. C., et al. 2024, IAU Symposium, 365, 207

- Christensen-Dalsgaard, J. 2002, Reviews in Modern Physics, 74, 1073

- Giles, P. M., Duvall, T. L., Scherrer, P. H., & Bogart, R. S. 1997, Nature, 390, 52

- Hanasoge, S. M., Duvall, T. L., & Sreenivasan, K. R. 2012, Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, 109, 11928

- Birch, A. C., Proxauf, B., Duvall, T. L., et al. 2024, Physics of Fluids, 36, 117136

- Hotta, H., Bekki, Y., Gizon, L., Noraz, Q., & Rast, M. 2023, Space Science Reviews, 219, 77

- Hanson, C. S., & Hanasoge, S. 2024, Physics of Fluids, 36, 086626

- Bekki, Y., Cameron, R. H., & Gizon, L. 2024, Science Advances, 10, eadk5643

- Mukhopadhyay, S., Bekki, Y., Xiaojue, Z., Gizon, L. 2025, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 696, A160

- Hanson, C. S., Hanasoge, S., & Sreenivasan, K. R. 2022, Nature Astronomy, 6, 708