Topology in Action: From Doughnuts to Quantum Devices

Mathematics has long served as the language of physics, helping us express and understand the laws of nature. From Newton’s second law, which led to the development of calculus, to Schrödinger’s equation in quantum mechanics, math enables us to model how the universe behaves. More abstract tools like group theory allow us to classify phases of matter by their symmetries - or more interestingly, by how those symmetries are broken.

But there’s another powerful branch of mathematics that’s become essential in modern physics, especially in studies of condensed matter systems: topology.

Topology studies the properties of spaces preserved under continuous deformations - stretching, bending, or twisting - without tearing or gluing. Imagine a rubber sheet: you can stretch or compress it into various forms, but as long as you don’t puncture it or attach new parts, the sheet remains topologically the same. These types of deformations, where the object is smoothly transformed without cutting or gluing, are called continuous deformations.

This is the key difference between topology and geometry. Geometry is concerned with precise measurements: angles, lengths, and areas. Two geometric shapes are considered different if those measurements differ. In contrast, topology focuses on the more abstract, structural aspects of a shape - how it’s connected, how many holes it has, whether it’s bounded or unbounded. In a topological sense, a coffee mug and a doughnut (torus) are the same because each has one hole; their detailed shapes and sizes are irrelevant (Fig 1).

How to quantify topology: Topological invariants

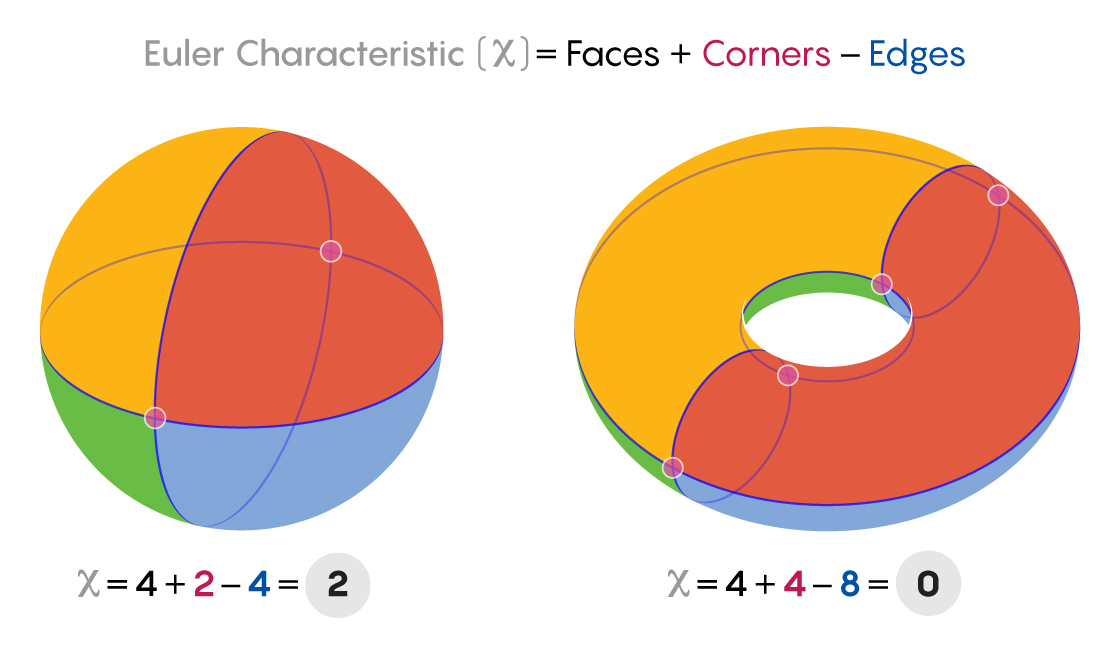

One of the oldest and simplest tools in topology is the Euler characteristic, a number associated with a geometric object. For a polyhedron, it’s defined as

where V is the number of vertices, E the number of edges, and F the number of faces. Take a tetrahedron: it has 4 vertices, 6 edges, and 4 faces. Plugging these into the formula gives . A cube has 8 vertices, 12 edges, and 6 faces, giving again. In fact, for any convex polyhedron, this number is always 2. This is no coincidence - these shapes all share the same underlying topology: they are topologically equivalent to a sphere.

What makes the Euler characteristic especially important is that it is a topological invariant - a quantity that remains unchanged under continuous deformations. So if you smoothly stretch or bend a cube into a sphere, its Euler characteristic stays the same. But if you punch a hole through the object, turning it into something like a torus (a doughnut shape), the Euler characteristic changes. For a torus, . That difference tells us the two shapes are topologically distinct-they belong to different “families” of spaces (Fig 2).

Topological invariants like the Euler characteristic allow mathematicians and physicists to classify shapes and spaces in a way that’s robust against local disturbances. Rather than tracking every detail, we focus on what truly matters: how the space is connected, how many holes or boundaries it has, and how it behaves as a whole.

The Problem of the Seven Bridges of Königsberg

Looking back through history, we find that topology originated from a mathematical problem posed by Euler in 1736 [1]. This problem, known as the Seven Bridges of Königsberg, holds historical significance. The problem is rooted in the unique geographical layout of the 18th-century city of Königsberg, then part of Prussia (now Kaliningrad, Russia). Situated along the Pregel River (now known as the Pregolya), the city encompassed two large islands-Kneiphof and Lomse-formed by the river’s branching channels. These islands were connected to each other and to the mainland by a total of seven bridges, creating a complex network of crossings (shown in Fig. 3) . This configuration led to a natural curiosity among the city’s inhabitants: is it possible to devise a walk through the city that crosses each bridge exactly once without retracing any steps?.

At first glance, this seems like a challenge of planning or persistence. One might start at one part of the city-say, on one of the islands-and attempt a path that carefully crosses each bridge without retracing any steps. Maybe try crossing to the northern bank, then loop through the western side, come back to the island, and finish on the southern bank. But no matter how carefully you plan, you’ll find yourself stuck: either forced to cross a bridge you’ve already used, or stranded with no remaining bridge to exit from.

People naturally attempted many such trial-and-error strategies. Some tried drawing the path, others tried tracing routes on a map. Yet none succeeded.

Euler’s solution and the birth of topology

In order to tackle the problem, Euler performed an abstraction on it - he removed all irrelevant features and information (such as the lengths of bridges and sizes of landmasses) and retained only the necessary components. He realised that each land mass can be simplified by representing it as a node (gray points in Fig. 4), and the seven bridges can be viewed as connecting edges between these nodes (orange lines in Fig. 4). In modern mathematics, this is called a graph.

Note that the initial problem that was posed was to figure out if it’s possible to traverse all bridges exactly once, without retracing steps. Euler noted that this problem is equivalent to figuring out whether one can construct a path along the graph that traverses every edge exactly once while passing through every node. In order to do this, certain constraints must be obeyed by the path. The starting and ending nodes (which correspond to the landmasses you start from and end at) must have at least one edge attached to them (you must have a bridge to move out of the starting landmass and a bridge to move into the final landmass). The other nodes must have an even number of edges connected to them, because if you enter a landmass using a bridge, you must exit it using a different bridge (retracing steps is not allowed).

In mathematical terms, if a non-terminal node is traversed times, it must therefore be attached to number of distinct edges (if you pass through a landmass 2 times, you must have 4 distinct bridges connecting it, otherwise you will retrace your steps at some point). Since only two nodes can be the terminal nodes, we have the constraint that at most two nodes in our graph can have an odd number of nodes; all other nodes must have an even number of nodes. This means that in order for a solution to exist, at most two of the landmasses can have an odd number of bridges attached to it, the rest of the regions must have an even number of bridges. In the specific graph problem we are encountering (Fig 4), we see that all the nodes in fact have an odd number of edges attached, thereby showing that no path with the specified requirements can be constructed for the Königsberg problem.

Note that the solution of the problem required no knowledge of the shape and size of the landmasses or the lengths of the bridges; the only relevant details were the connections among the nodes. In fact, distorting the size and shapes of the nodes or displacing the nodes by small distances does not alter the solution in any way. The solution is therefore impervious to continuous deformations, and is dictated purely by the topology of the graph. In this way, the Königsberg bridge problem also led to the birth of topology as a new field of mathematics.

Topology in action: The quantum hall effect

Topology is not just a fancy mathematical construct-it plays a profound role in modern physics, particularly in understanding exotic phases of matter. A classic example is the quantum Hall effect. This is a juiced-up version of the classical Hall effect [2] in which a perpendicular magnetic field applied on a current deflects the electrons perpendicular to the current in the plane perpendicular to the field, and makes them accumulate on the boundaries, due to which an electric voltage (Hall voltage, ) develops in the same direction. The Hall resistance , defined as the ratio of Hall voltage to longitudinal current (), increases linearly with magnetic field in the classical case:

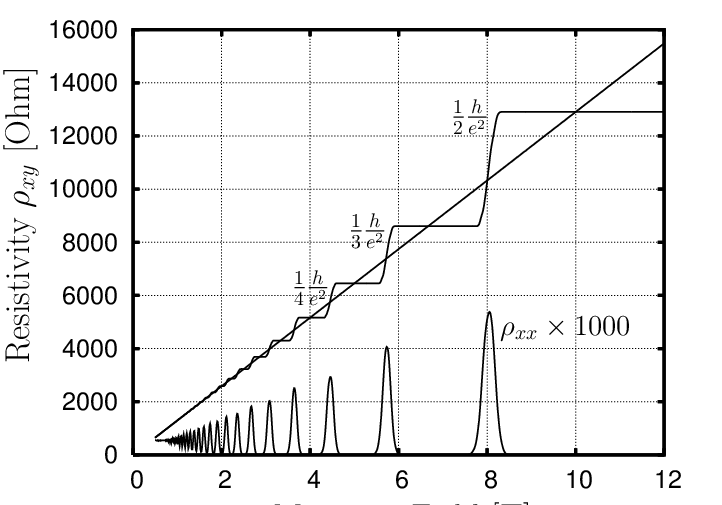

However, in a two-dimensional system with a bit of disorder (e.g., impurities or imperfections in the material) - such as a thin film of semiconductor subjected to very high magnetic fields and very low temperatures, the Hall resistance no longer follows a smooth linear trend. Instead, it exhibits a series of quantized, precise plateaus - meaning the Hall resistance takes on discrete values, each corresponding to a specific fraction involving fundamental constants (Fig 5):

where and are the Plancks constant and charge of electron. This is the quantum hall effect [3]. Its most remarkable feature is the robustness of these plateaus: they are unaffected by imperfections in the material, such as impurities or small variations in geometry. This stability is a hallmark of topological phases of matter [4].

A peculiar property of magnetic fields is that they have a strong directionality - they localise electrons in one direction and force them to move in another direction. This localisation has a severe effect on the energy levels of the 2D electrons. In the absence of magnetic fields and any impurities (disorder), the energy levels vary smoothly (left, Fig 6);

adding impurities and turning on a perpendicular magnetic field makes these levels bunch up into discrete bands called Landau levels (Fig 6):

Each value of represents a distinct Landau level. Each Landau level is macroscopically degenerate, consisting of a huge number of electronic states at the same energy. These degenerate states in each Landau level are spatially distributed along the transverse (Hall) direction, each state localised (cannot travel too far) at various positions [5], but are extended (can travel from one end to the other end) in the longitudinal direction.

Origin of quantisation: Chiral edge states

It’s important to note that disorder plays a crucial role in enabling the quantized Hall plateaus. By localizing most bulk states in between Landau levels, disorder prevents small changes in electron density from altering the number of conducting channels. This makes the quantization experimentally robust.

We will now figure out how topological considerations play into the robustness of the quantum hall resistivity plateaus, using a semiclassical picture. As mentioned in the previous section, each Landau level has multiple states with the same energy but placed at various positions along the localised direction. Away from the edges of the sample, the electrons in these states circulate in closed cyclotron orbits due to the magnetic field and do not contribute to any conduction mechanism. What happens when we consider states that are very close to the boundary, at a distance less than the radius of the cyclotron orbits? This is shown in the blue and red trajectories of Fig 7 - under the influence of the magnetic field, electrons try to exit the sample but of course cannot, and they reflect off the edge, forming skipping orbits. These states therefore extend along the length of the sample, and are not localised [6].

The important point is that the directionality of the magnetic field forces these delocalised skipping orbits to move in a certain direction - rightwards on the top edge and leftwards on the bottom edge, as shown in Fig 7. There cannot be any left(right)-moving states on the upper(lower) edge. Such states that move only left or right are called chiral states, and are generated because of the strong magnetic field [3]. More precisely, such chiral edge states result from the time-reversal symmetry-breaking nature of the magnetic field. A video of a time-reversal symmetric system looks the same if the video is played backwards. The magnetic field makes this impossible, because it separates the left and right-going states and places them on different edges - playing the video backwards would lead to a switch in the behaviour of the two edges. This separation also makes them robust - an electron travelling along an edge (as mentioned in the previous paragraph, the edge states are delocalised and can therefore carry current) cannot stray from its path without expending a large energy cost. To do so, it must “jump” to the other edge state (which is of similar energy), but since these states are widely separated in real space (they lie on opposite edges), such processes are effectively impossible.

How does the presence of chiral edge states explain the quantisation of resistivity in the plateaus? Given that each Landau level contributes one pair of robust delocalised current-carrying edge states moving in opposite directions on the opposite edges of the sample, applying a hall voltage difference between the left and right states leads to a net current flowing along the edge of each Landau level. Because of the presence of energy gaps between the Landau levels, the number of Landau levels that are occupied (below the dashed line in Fig 8) cannot change continuously, but can only increase by one each time the dashed line passes through the center of a Landau level. If the number of Landau levels below the dashed line is , there are such edge states that have electrons in them and hence contribute a current . The Hall resistance is the total Hall current divided by the Hall voltage , which comes out to be , which is clearly quantised through the integer .

What’s the topological invariant?

What is the role of topology in all of this? The quantisation arises owing to the robustness of two aspects:

- robustness of the gaps in the Landau level which ensures the number of edge states do not change smoothly but rather in discrete steps, and

- robustness of the chiral edge states that can carry the Hall current. Both of these are consequences of the non-zero magnetic field, which sets the topology of the wavefunctions (the separation of left and right moving states at the two edges). The topology remains undisturbed under small deformations (such as changing, by small amounts, the magnetic field, size of the sample, the temperature or the disorder), and can only change under large deformations (such as switching off the magnetic field entirely or drastically reducing the system size).

Similar to the Euler characteristic which acted as a topological invariant for polyhedrons, is there again an invariant in this context that sets the topology of the wavefunction? In quantum mechanics, the state of an electron moving with a certain momentum is described by a wavefunction with a phase. As the momentum changes, this phase can twist and evolve, and is captured by something called the Berry curvature . But what does the Berry curvature have to do with the Hall conductivity? Well, it turns out that the Hall conductivity in two dimensions can be expressed as the integral, in momentum space, of the Berry curvature of the wavefunction - the more the wavefunction “curves” in momentum space, the more is the conductivity. [7]

What does this have to do with topological quantisation? It can be shown that the integral of the Berry curvature is always an integer multiple of :

where the integral is over momentum space (MS), represents the differential area in momentum space and is the Berry curvature at any point, acting as the integrand. The quantised nature is reflected in the fact that (on the right hand side of the equation) is necessarily an integer. This is analogous to the way the total curvature of a closed curve in 2D geometry - say, walking around a point - always adds up to an integer multiple of 2π, depending on how many times the path winds around that point (Fig 9). Similarly, the Berry curvature accumulates in momentum space, and its total integral - the Chern number ()- counts how many times the quantum wavefunction twists or “wraps” around the space of momenta. This argument therefore links the Hall conductivity to the Chern number:

The Chern number is a topological invariant; it is insensitive to local details of the wavefunction and only depends on how many times the wavefunction wraps around in momentum space. This topological nature of the Chern number explains the robustness of the Hall conductivity: it cannot change gradually as experimental conditions are tweaked. Instead, it only jumps when the system undergoes a true topological transition - such as when the chemical potential crosses a Landau level and a new chiral edge state emerges. This is why the plateaus are sharp and stable: they reflect changes in an integer-valued invariant that counts how the wavefunction “winds” in momentum space [8].

Beyond quantum hall: Topological insulators

While the quantum Hall effect relies on the breaking of time-reversal symmetry (TRS) to generate its chiral edge states and quantized conductance, physicists have discovered materials, referred to as topological insulators [9], that can support topologically-protected edge states even in the absence of any external magnetic field. Instead of a magnetic field, these materials require strong spin-orbit coupling (SOC) - an effect where an electron’s motion through the crystal lattice is intimately linked to its intrinsic angular momentum (spin). In fact, SOC acts like an internal, spin-dependent magnetic field, but one that does not break TRS. The presence of SOC gives rise to helical edge states: at each edge, electrons of opposite spin travel in opposite directions. This mechanism filters out spin-up and spin-down electrons into opposite directions at the edges, forming spin-polarized, counter-propagating states at each edge - a hallmark of the quantum spin Hall effect (Fig 10).

Importantly, due to TRS, backscattering between the opposite spin states at each edge is prohibited; such a scattering process is not allowed by the symmetry. This makes these edge channels robust against non-magnetic disorder (magnetic disorder will allow scattering between the opposite spin channels at each edge). The edges of a topological insulator exhibit perfect transport, meaning no energy is lost as heat, and the number of conducting pathways can be tuned. Though measuring spin currents is more subtle than charge currents, advanced experimental techniques have made such measurements possible, confirming the presence of spin transport along the edges.

Topology meets technology: The promise of topological qubits

A natural question arises: why should we care about the topological properties of quantum systems? One compelling answer lies in quantum computing!

Quantum computers leverage the unique property of quantum particles to exist in multiple states simultaneously (superposition) to store information in qubits. This enables them to solve problems exponentially faster than classical computers, which rely on classical bits (which are either 0 or 1). The main challenge in this approach is that qubits are extremely fragile - tiny interactions with the environment can decohere the information, leading to errors in computation.

Topological quantum computation addresses this by using topological qubits that encode information not in the precise configuration of a system, but in its topological properties - features that are preserved under continuous deformation [10]. One approach towards this is by using anyons - exotic emergent particles that appear in two dimensions. The collective quantum state of such systems depends on global properties such as the winding pattern of the anyons around each other (a process known as braiding), and is independent of the precise geometric or local details [11]. This topological nature of the quantum state makes the system inherently robust against local disturbances or errors, providing a promising foundation for fault-tolerant quantum computation [12].

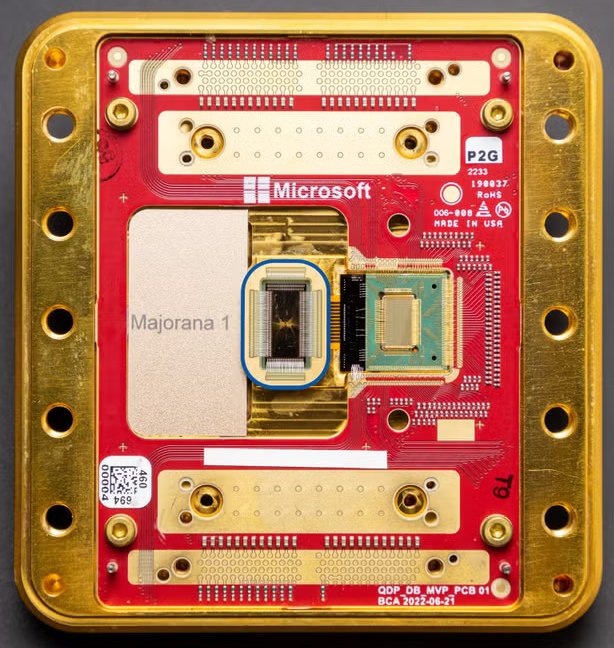

Several platforms are being explored to realize these ideas, including systems based on Majorana modes [13]. Recently, Microsoft published a study in Nature that carries out measurements on a topological superconductor [14] (Fig 11). In topological superconductors, it is theorised that the lowest-energy excitation corresponds to a single electron being nonlocally stored between two spatially separated Majorana modes. Microsoft’s results show evidence for an extra electron occupying a low-energy bound state, consistent with theoretical predictions for a Majorana mode. While the report is not unequivocal in the demonstration of the topological Majorana modes and does not rule out non-topological explanations, it highly constrains such non-topological states and advances the field of topological computation in a concrete way by demonstrating that such measurements are certainly consistent with topological computation.

While the full experimental verification of Majorana-based qubits remains an ongoing challenge - previous claims have been met with skepticism and rigorous scrutiny - Microsoft’s results are a tangible step forward in the quest to harness topological phases of matter for real-world quantum computing. If successful, it would validate years of theoretical predictions and could signal a turning point where topology moves from abstract mathematics into the heart of practical, next-generation technologies.

References

- S. C. Carlson, “Königsberg bridge problem | mathematics,” Encyclopædia Britannica. 2019

- Steven H. Simon, The Oxford Solid State Basics, Oxford University Press, 2013.

- David Tong, Lectures on the Quantum Hall Effect. arXiv:1606.06687 (2016)

- Steven H. Simon, Topological Quantum: Lecture Notes, (2016)

- Landau, L.D. and Lifshitz, E.M. (1981) Quantum Mechanics: Non-Relativistic Theory

- B. I. Halperin, Quantized Hall conductance, current-carrying edge states, and the existence of extended states in a two-dimensional disordered potential, Phys. Rev. B 25, 2185 (1982)

- Eduardo Fradkin, Field Theories of Condensed Matter Physics, Cambridge University Press (2013)

- D. J. Thouless, M. Kohmoto, M. P. Nightingale, and M. den Nijs, “Quantized Hall Conductance in a Two-Dimensional Periodic Potential,” Physical Review Letters, vol. 49, no. 6, pp. 405–408, Aug. 1982

- M. Z. Hasan and C. L. Kane. Topological insulators. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 3045 (2010)

- Memon, Q. A., Al Ahmad, M., & Pecht, M. (2024). Quantum Computing: Navigating the Future of Computation, Challenges, and Technological Breakthroughs. Quantum Reports, 6(4), 627-663.

- Sukhpal Singh Gill, Oktay Cetinkaya et al. Quantum Computing: Vision and Challenges. arXiv:2403.02240. 2024

- A. Yu. Kitaev, “Fault-tolerant quantum computation by anyons,” Annals of Physics, vol. 303, no. 1, pp. 2–30, Jan. 2003

- Chetan Nayak, Steven H. Simon, Ady Stern, Michael Freedman, and Sankar Das Sarma. Non-Abelian anyons and topological quantum computation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 80, 1083 (2008)

- Microsoft Azure Quantum., Aghaee, M., Alcaraz Ramirez, A. et al. Interferometric single-shot parity measurement in InAs–Al hybrid devices. Nature 638, 651–655 (2025)