A Century of Quantum Mechanics: From Paradoxes to Possibilities

In 2026, the global scientific community will celebrate 100 years of quantum mechanics - a theory that has transformed how we understand nature and helped shape today’s technologies. Born in the early 20th century from experiments that defied the rules of classical physics, quantum mechanics has since become central to physics, chemistry, materials science, computing, and even our understanding of life itself. As we mark this centennial, this article looks back at its historical origins, explores how it continues to shape new discoveries, and considers what the next century of quantum science may bring.

A Historic Journey: Why Quantum Mechanics Was Needed

Prior to the advent of quantum mechanics, physics was considered mostly complete through Newtonian mechanics and Maxwell’s electrodynamics. However, through the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, significant experimental results were discovered that challenged classical predictions.

The first major challenge came from blackbody radiation. According to the Rayleigh-Jeans law, classical physics predicted that hot objects emit arbitrarily large amounts of energy at higher frequencies, leading to the infamous ultraviolet catastrophe. In 1900, Max Planck resolved this paradox by proposing that energy is absorbed only in discrete packets, or quanta [1] (the word quantum originates from the Latin word “quantus,” meaning “how much,”!).

A few years later, Albert Einstein extended this idea to light itself. His 1905 explanation of the photoelectric effect showed that light behaves as if it’s made up of individual particles - later called photons - rather than just waves [2]. This challenged the long-standing belief that light was purely a wave, and hinted that nature might be more discrete than continuous.

Further inconsistencies emerged in the field of atomic physics. According to the laws of classical electrodynamics, an electron orbiting the nucleus should continuously lose energy by emitting electromagnetic radiation and spiral inward into the nucleus, leading to the collapse of atoms. This was of course at odds with the observed atomic stability in nature. To resolve this paradox, in 1913, Niels Bohr proposed his ground-breaking model of the hydrogen atom [3], where electrons occupy fixed discrete energy levels, and can transition between the levels only by absorbing or emitting definite amounts of energy. The fact that the electron cannot absorb or emit arbitrary amounts of energy prevented its collapse. While Bohr’s model successfully explained the Balmer series (spectral lines to n=2) of hydrogen,the absence of a substantial theoretical foundation meant that it failed to describe more complex atoms.

The final blow to the fundamentals of classical mechanics came with the emergence of Wave-Particle Duality. Louis de Broglie (1924) introduced the idea of matter waves, proposing that, like light, electrons exhibit wave-like properties [4]. Davisson and Germer (1927) experimentally corroborated this concept by observing electron diffraction [5], demonstrating that electrons behave like waves under certain conditions.

These findings demanded an entirely new theoretical framework. In the mid-1920s, Werner Heisenberg and Erwin Schrödinger independently developed quantum mechanics, through matrix mechanics [6] and wave mechanics [7] respectively. Though they looked different, the two approaches turned out to be mathematically equivalent. Shortly afterward, Paul Dirac combined quantum mechanics and special relativity to predict the existence of antimatter [9]. All of these advancements combined to create modern quantum mechanics, introducing a new era of physics.

Expanding Domains: Quantum Field Theory & Beyond

While early quantum mechanics worked well for predicting the behaviour of atoms and molecules, it had limitations.:

- it wasn’t compatible with Einstein’s special relativity, and

- it couldn’t account for situations involving the creation and destruction of particles (phenomena common in high-energy physics).

To address these limitations, physicists developed Quantum Field Theory (QFT) in the mid-20th century by merging quantum mechanics with special relativity.

At the heart of QFT is a simple but revolutionary idea: the fundamental building blocks of nature are not particles, but fields - mathematical objects that can take on values at every point in space and time [15]. Imagine space filled with invisible, vibrating fields, like a sea of tensioned fabric stretched across the universe. A particle, in this view, is just a tiny ripple or excitation in one of these fields. Each type of particle that we can observe or know to exist - electrons, photons, quarks - is tied to a different field. These fields can interact, combine, and exchange energy, allowing QFT to describe complex processes like particle collisions and the forces between them.[15].

This framework is the foundation of the standard model of particle physics, our best theory of fundamental particles and their interactions (excluding gravity) [16]. Within the standard model,

- quantum electrodynamics (QED) describes how light and matter interact [11, 12]. It is the most precisely tested theory in all of physics,

- quantum chromodynamics (QCD) explains the strong force that binds quarks together inside protons and neutrons, and

- electroweak theory unifies the above two forces into a single description [17, 18].

In one of the most climactic conclusions, the discovery of the Higgs boson at CERN in 2012 [19] confirmed the presence of the Higgs field that had been predicted for a long time and this completed the Standard Model. By interacting with the Higgs field, elementary particles such as quarks and electrons obtain mass, through the Brout-Englert-Higgs mechanism (or the Higgs mechanism in short).

Expanding Technologies via Quantum Computing

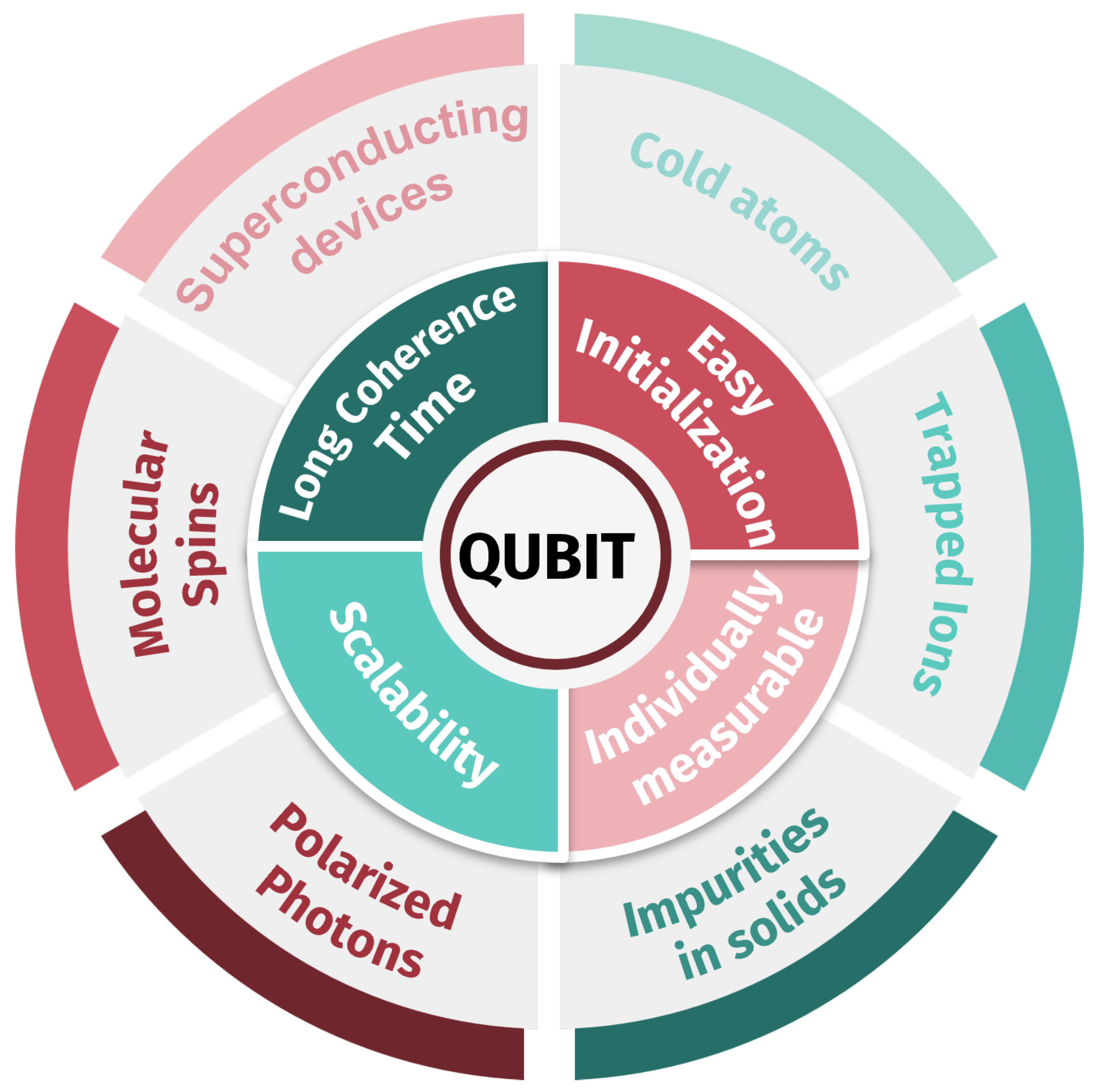

In recent years, quantum computing has emerged as one of the most exciting frontiers in technology. Unlike binary classical switches, quantum states (quantum bits or qubits) can be both 0 and 1 at the same time, thanks to a phenomenon called superposition. Even more remarkably, these qubits can become entangled, meaning the state of one qubit is linked to another, no matter how far apart they are. These uniquely quantum properties allow certain tasks to be performed much faster than with classical computers [23].

You can think of a quantum computer like a massively parallel multitasker, exploring many computational paths at once, whereas a classical computer checks them one at a time. By leveraging these properties, quantum algorithms often offer massive speedups compared to their classical counterparts. Shor’s quantum algorithm can factor large numbers much faster than classical methods, threatening current cryptography [24]. In addition, Grover’s algorithm offers a quadratic speedup in search tasks [25].

However, unlike classical bits, quantum bits (or qubits) are extremely fragile and prone to errors due to decoherence and noise from their environment. This poses a serious problem for designing practical quantum computers that can operate reliably over long periods. Recent breakthroughs in quantum error correction and the development of fault-tolerant architectures have brought us significantly closer to building practical quantum computers [26]. Quantum error correction aims to safeguard information by encoding a single logical qubit into many physical ones, allowing the system to detect and correct errors without directly measuring the qubits themselves. Major tech companies such as Google, IBM, and Microsoft are actively pursuing scalable quantum processors [27, 42].

Meanwhile, quantum communication technologies are also making rapid progress. A prominent application is Quantum Key Distribution (QKD), which allows two parties to exchange cryptographic keys with security guaranteed by quantum mechanics [28]. Unlike classical encryption, QKD is fundamentally immune to eavesdropping, as any attempt to intercept the key disturbs the quantum system and reveals the intrusion. This technology could form the basis of ultra-secure communication networks in the near future.

Real-World Applications: Chemistry, Biology, Materials Science, and more

Quantum mechanics has numerous real-world applications in science and engineering. In quantum chemistry, it helps scientists simulate how atoms bond to form molecules, enabling the design of new materials and accelerating drug discovery. Using quantum models, researchers can predict how molecules will interact in complex environments, such as inside cells or on catalytic surfaces [29]. In quantum biology, some natural processes appear to rely on quantum effects. For instance, plants may use quantum coherence to transfer energy efficiently during photosynthesis, and migratory birds might sense the Earth’s magnetic field using entangled electron spins [30].

Quantum mechanics has also transformed our understanding of materials, leading to the discovery and engineering of exotic quantum materials. Notable examples include topological insulators, which conduct electricity on their surfaces but remain insulating inside, and high-temperature superconductors, which carry electric current without resistance at relatively high temperatures. These materials challenge traditional theories of matter and offer promising pathways for developing next-generation electronics, energy-efficient power systems, and quantum devices [31, 32].

Apart from materials, quantum mechanics also plays a key role in precision measurement techniques. Atomic clocks, the most accurate time-keeping devices on the planet, use the frequency of transitions between energy levels of cesium or rubidium atoms, and are used in global positioning systems (GPS) and gravitational wave detectors like LIGO. These applications illustrate the pervasive impact of the field across multiple disciplines [33, 34].

Unfinished Business: Some Open Problems

Quantum mechanics is among the most successful and precisely tested theories in all of science, yet it still leaves many deep questions unanswered. We point out some of them here.

##= The Measurement problem

Quantum theory predicts that a system evolves smoothly and predictably, according to the Schrödinger equation - the quantum analogue of Newton’s second law of motion. This leads to a strange outcome: as mentioned earlier, particles can exist in superpositions, or combinations of multiple possible states at once. But whenever we measure such a system, we only see a single outcome. Why?

This puzzle is known as the measurement problem. It arises because the standard rules of quantum mechanics don’t explain what exactly happens during a measurement or why the wavefunction collapses to one result. Is collapse a physical process? Is it just a change in our knowledge? Or is something deeper going on? No consensus exists yet.

Solving the measurement problem is crucial because it touches the very heart of quantum mechanics and of reality itself. It may be the key to explaining how the quantum world, with all its uncertainty and fuzziness, gives rise to the clear, definite experiences of the classical world we live in.

##= An Overarching Theory For Quantum Matter

Since the landmark discoveries of high-temperature superconductivity and fractional quantum hall effect in the 1980s, scientists have come to realise that several materials with strong inter-electron correlations show exotic properties. The physics of such materials was found to be governed by (i) topological considerations (where global properties of the wavefunction determine the physics instead of local details) and (ii) strong many-particle entanglement (a phenomenon in which the configurations of multiple particles get locked with each other), and they have come to be known as quantum matter. Researchers are working to find unified frameworks that can explain how these systems behave and predict new materials with similar strange properties. A complete theory of quantum matter could revolutionize technologies like superconductors, quantum computers, and even generate new states of matter.

##= Quantum gravity and unification

One of the biggest unsolved problems in physics is how to combine quantum mechanics with general relativity (Einstein’s theory of gravity). While quantum mechanics works extremely well for tiny particles, general relativity describes how space and time behave on large scales, like planets, stars, and galaxies. But when both theories are needed, such as near a black hole or during the Big Bang, they lead to conflicting results. The challenge is that gravity, as described by general relativity, treats space and time as a smooth, continuous fabric. But quantum mechanics suggests that, at the smallest scales, this fabric should be made of discrete chunks - like pixels in an image. When scientists try to apply the methods of quantum field theory to gravity, the math blows up with infinities that can’t be handled, a problem known as non-renormalizability.

Various approaches (string theory, loop quantum gravity, etc.) attempt a unification, but no fully successful theory has emerged. Until quantum gravity is solved, our understanding of the universe’s origin, black holes, and the deepest laws of nature remains incomplete. This problem is significant because it stands at the foundation of all physics: without it, we cannot claim to have a complete theory that covers both the very large (cosmology) and the very small (quantum particles).

Looking Ahead: The Next Century of Quantum Mechanics

As quantum mechanics turns 100, it remains one of the most vibrant and forward-looking areas of science. One emerging frontier is quantum thermodynamics, where researchers are exploring technologies like quantum heat engines and quantum batteries - devices that could one day store and convert energy far more efficiently than anything classical physics allows.

The coming years may also bring what physicists call a second quantum revolution - a new era driven by quantum technologies that promise to transform computing, communication, and sensing. From unbreakable encryption to faster-than-ever computation, quantum mechanics is poised to impact industries and everyday life in ways we are only beginning to imagine. In 2026, the global scientific community will mark this centennial milestone with lectures, exhibitions, and conferences hosted by institutions such as CERN, the Max Planck Institute, and the American Physical Society.

It’s a moment not only to celebrate how far we’ve come, but also to look ahead. Because if the past century of quantum mechanics has taught us anything, it’s that the quantum world is full of surprises. And we’ve only just begun to explore it.

References

- Planck, M. (1901). On the law of distribution of energy in the normal spectrum. Annalen der Physik, 4(3), 553.

- Einstein, A. (1905). On a heuristic point of view about the creation and conversion of light. Annalen der Physik, 17(6), 132-148.

- Schrödinger, E. (1935). Die gegenwärtige Situation in der Quantenmechanik. Naturwissenschaften, 23(48), 807–812.

- Trimmer, J. D. (1980). The present situation in quantum mechanics: A translation of Schrödinger’s Cat Paradox paper. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 124(5), 323–338.

- Slater, J. C., & Frank, N. H. (1933). Introduction to theoretical physics. McGraw-Hill.

- Schrödinger, E. (1926). Quantisierung als Eigenwertproblem. Annalen der Physik, 79(4), 361–376.

- Heisenberg, W. (1925). Über quantentheoretische Umdeutung kinematischer und mechanischer Beziehungen. Zeitschrift für Physik, 33(1), 879–893.

- Bohr, N. (1913). On the constitution of atoms and molecules. Philosophical Magazine, 26(151), 1–25.

- Sommerfeld, A. (1916). Zur Quantentheorie der Spektrallinien. Annalen der Physik, 356(17), 1–94.

- de Broglie, L. (1924). Recherches sur la théorie des quanta. Annales de Physique, 10(1), 22–128.

- Dirac, P. A. M. (1928). The quantum theory of the electron. Proceedings of the Royal Society A, 117(778), 610–624.

- Feynman, R. P. (1948). Space-time approach to non-relativistic quantum mechanics. Reviews of Modern Physics, 20(2), 367–387.

- Ashcroft, N. W., & Mermin, N. D. (1976). Solid state physics. Saunders College.

- Kittel, C. (2004). Introduction to solid state physics (8th ed.). Wiley.

- Weinberg, S. (1995). The quantum theory of fields (Vol. 1). Cambridge University Press.

- Griffiths, D. (2008). Introduction to elementary particles. Wiley.

- Gross, D. J., Wilczek, F., & Politzer, H. D. (1973). Asymptotically free gauge theories. Physical Review Letters, 30(26), 1343–1346.

- Glashow, S. L., Salam, A., & Weinberg, S. (1979). Electroweak unification. Scientific American, 241(6), 66–75.

- Aad, G. et al. (2012). Observation of a new particle in the search for the Standard Model Higgs boson. Physics Letters B, 716(1), 1–29.

- Wess, J., & Zumino, B. (1974). Supersymmetry and the gauge hierarchy problem. Nuclear Physics B, 70(1), 39–50.

- Maldacena, J. (1998). The large-N limit of superconformal field theories. Advances in Theoretical and Mathematical Physics, 2, 231–252.

- Peebles, P. J. E., & Ratra, B. (2003). The cosmological constant and dark energy. Reviews of Modern Physics, 75(2), 559–606.

- Nielsen, M. A., & Chuang, I. L. (2010). Quantum computation and quantum information (10th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Shor, P. W. (1997). Polynomial-time algorithms for prime factorization. SIAM Journal on Computing, 26(5), 1484–1509.

- Grover, L. K. (1996). A fast quantum mechanical algorithm for database search. Proceedings of the 28th Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing, 212–219.

- Gottesman, D. (1997). Stabilizer codes and quantum error correction. Physical Review A, 54(3), 1862–1881.

- Arute, F. et al. (2019). Quantum supremacy using a programmable superconducting processor. Nature, 574, 505–510.

- Gisin, N., Ribordy, G., Tittel, W., & Zbinden, H. (2002). Quantum cryptography. Reviews of Modern Physics, 74(1), 145–195.

- Dirac, P. A. M. (1929). Quantum mechanics of many-electron systems. Proceedings of the Royal Society A, 123(792), 714–733.

- Warshel, A., & Levitt, M. (1976). Theoretical studies of enzymatic reactions. Journal of Molecular Biology, 103(2), 227–249.

- Hasan, M. Z., & Kane, C. L. (2010). Topological insulators. Reviews of Modern Physics, 82(4), 3045–3067.

- Tokura, Y., Kawasaki, M., & Nagaosa, N. (2017). Emergent functions of quantum materials. Nature Physics, 13, 1056–1068.

- Abbott, B. P. et al. (2016). Observation of gravitational waves from a binary black hole merger. Physical Review Letters, 116(6), 061102.

- Ludlow, A. D., Boyd, M. M., Ye, J., Peik, E., & Schmidt, P. O. (2015). Optical atomic clocks. Reviews of Modern Physics, 87(2), 637–701.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2019). Quantum computing: Progress and prospects. The National Academies Press.

- Kosloff, R. (2013). Quantum thermodynamics: A dynamical viewpoint. Entropy, 15(6), 2100–2128.

- Everett, H. (1957). Relative state formulation of quantum mechanics. Reviews of Modern Physics, 29(3), 454–462.

- Bohm, D. (1952). A suggested interpretation of the quantum theory in terms of hidden variables. Physical Review, 85(2), 166–179.

- Quantum mechanics centennial celebrations planned for 2026. (2025). Physics Today, 74(12), 24.

- CERN announces symposium for quantum mechanics 100th anniversary. (2025). CERN Courier, 65(9), 5.

- Nobel Foundation to commemorate a century of quantum mechanics. (2025). Nature, 528, 465.

- Microsoft Azure Quantum., Aghaee, M., Alcaraz Ramirez, A. et al. Interferometric single-shot parity measurement in InAs–Al hybrid devices. Nature 638, 651–655 (2025)

- E. J. Warrant, Unravelling the enigma of bird magnetoreception, Nature, vol. 594, no. 7864, pp. 497–498, Jun. 2021

- K. Intonti et al., The Second Quantum Revolution: Unexplored Facts and Latest News, Encyclopedia, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 630–671, Jun. 2024