The Chemical Ballet: How Volatiles Orchestrate Pest and Predator Behaviour

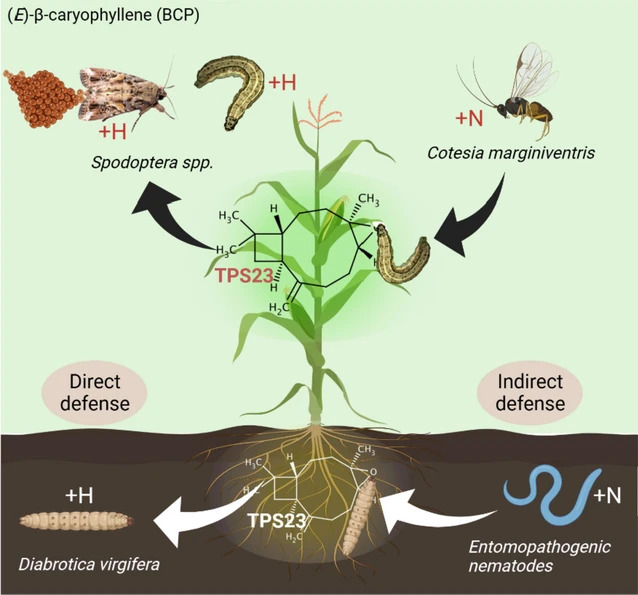

Plants are much more than the silent, passive participants in the complex and grand symphony of life. When trapped and confronted by noxious enemies, they can come up with an incredible range of strategies for survival, thriving, and fighting back. Research has shown that plants can rapidly and accurately recognise their attackers, relaying this information to beneficial parasitic wasps [1]—a finding with profound implications for enhancing integrated pest management programs. The quintessence of these strategies lies in their capacity to release volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that act as invisible communication agents, free-floating in the air. Similarly, the sesquiterpene (E)-β-caryophyllene [2] has been identified as an attractant for entomopathogenic nematodes to maize roots below ground. These compounds narrate tales of survival that are included in the stories of multitrophic interactions that, among themselves, maintain equilibrium within ecosystems.

A Hidden Symphony

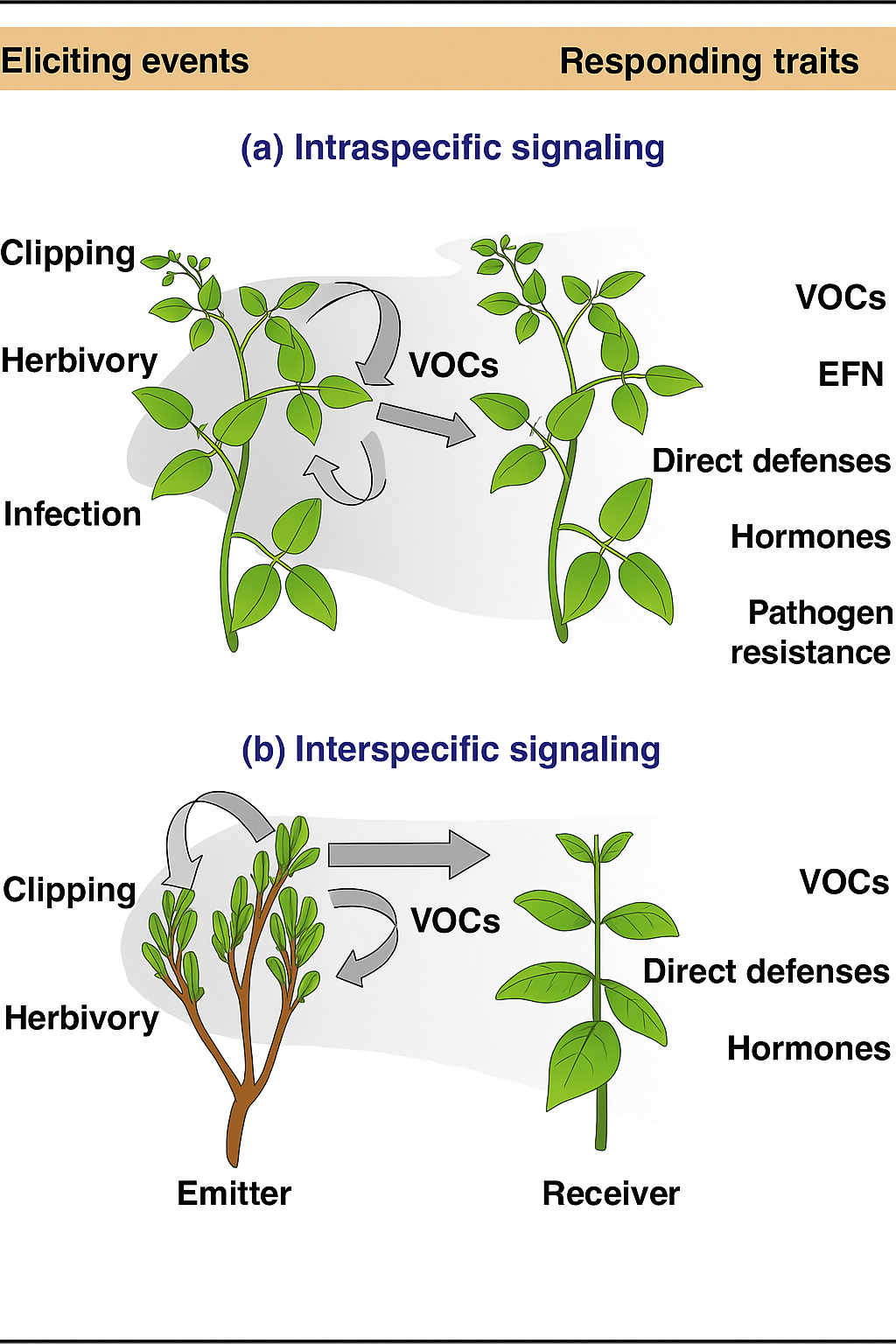

Imagine a forest where the air hums with the quiet rustling of leaves—plants engaging in whispered but potent dialogues. They are the green maestros conducting an orchestra, playing their music of survival using VOCs [3]. These aerosol signals are emitted by plants in response to biotic stresses, such as herbivore feeding, pathogen attack, or competition by neighbouring plants, as well as abiotic stressors like drought and temperature variations that play key roles in attracting pollinators, deterring herbivores, and signalling threats. We often fail to recognise that these VOCs are the plants’ sophisticated method of communication. They can be used to warn other individuals, whether it be a friend or foe. Every note in this silent symphony is significant. VOCs emitted by plants rise above their seeming immobility to become actors in this silent drama of survival.

Signals of Distress

An injured leaf, when chomped by the mandibles of an herbivore, gets transformed into a secret arena of combat. These compounds don’t just linger in the air—they travel and interact with other organisms. We do not see the affected plant cry. Rather, it sends a SOS into the atmosphere—the VOCs. They are transported through the canopy, connecting with nearby plants to convey the looming bad news. This surveillance enables neighbouring plants to prepare themselves by synthesising toxins or making their physical defences more fortified. But the story doesn’t end here. Plants also use VOCs to assert dominance in the competition for space and resources. Some species are known to produce compounds known as allelochemicals that limit seed germination of the adjacent plants, preventing hostile neighbours from flourishing. This symbiosis of cooperation and conflict in plant communities drives the complexity of VOC-mediated interactions.

The Dance with Herbivores

As herbivores take the stage, the story ramps up. However, it’s no easy feat for a voracious, hungry insect to find its next target. Plants, equipped with their VOC defences, shroud themselves in “chemical invisibility,” concealing the cues that herbivores depend on to find their food sources. This deception bewilders the attackers, causing them to overlook their hosts. The environment of the plant transforms into a fortress, making potential feeders stumble upon a bubble of chemical deterrents. However, plants aren’t just trying to protect themselves; they have some clever tricks up their sleeves. Some VOCs mimic odours associated with dangerous and non-host plants, which the herbivores quickly learn to avoid. Despite this, in some instances, these compounds can even trap herbivores or lure them to locations where they are unlikely to survive.

Rallying Reinforcements

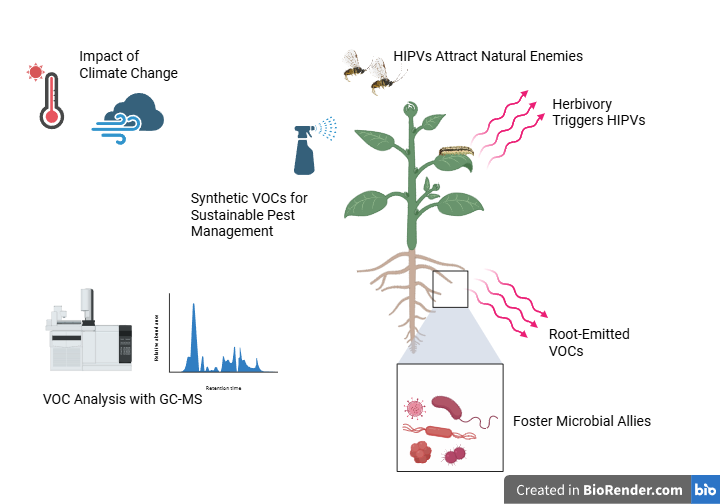

The herbivore-induced plant volatiles (HIPVs) serve as a chemical “alarm” that attracts the natural enemies of herbivores, such as their predators and parasitoids. Herbivory sets off a signal transduction pathway inside the plant, resulting in the biosynthesis and release of VOCs such as green leaf volatiles (GLVs), jasmonates, and terpenoids [4], that lure in parasitoids that attack aphids or larvae feeding on the plant. They are the plant’s unwitting natural enemies, but allies that turn against the parasite.

Volatiles Across Trophic Levels

VOCs feed into the web of interactions much further afield from that immediate plant-herbivore-predator triad. Beneath the soil, a new play commences. Roots release VOCs that shape the microbial community in the rhizosphere [5], selectively attracting beneficial microbes such as nitrogen-fixing bacteria and mycorrhizal fungi. These friendly microbe allies do the work of making nutrients available and plant growth, which makes plants grow. VOCs act to suppress the development or infection of a wide range of harmful pathogens, at the same time, conserving plant health. In addition, VOC-driven interaction drives the functionality of nutrient cycling (promoting organic matter decomposition and nutrient release back into soil) as well. That belowground network of connections allows VOCs to help the plant out above ground and even below the soil, where unseen sidekicks are doing their thing to keep plants alive.

Experimental Insights

VOCs have long since opened a new area of research, unlocking the hidden language of plants and deeper into scientific intrigue. It is thanks to the introduction of modern and sophisticated instrumental analytical techniques like Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) and complex olfactometric systems that we are now able to unravel the underlying chemical composition of VOC blends with amazing accuracy. GC-MS helps in the separation and identification of VOCs in a mixture and helps decode complex VOC blends by pinpointing individual components, linking chemical identity with biological activity such as insect attraction or repulsion. These technologies have cracked the code not only on how plants can communicate with each other and other members of their community, but also how they defend themselves from herbivore attack, appeal to organisms and even manipulate their environment using complex strategies.

Field Applications

VOC research has practically applicable results as exhilarating as they are profound. Plants communicate with chemical signals that serve as cues about the presence of natural enemies, and synthetic VOCs just sort of mimic these signals to disperse biological controls for crop protection in agricultural fields. For instance, synthetic terpenes that are modelled after natural HIPVs are being tested to attract beneficial insects directly to threatened crops [6].

VOC-based strategies are an environmentally benign alternative to the currently used chemical pesticides with low environmental and health risks. While broad-spectrum pesticides kill both the pest and some pests’ natural enemies, along with other helpful organisms.

Implications for Ecosystem Stability

VOCs’ significance in preserving ecological balance is highlighted by their function in mediating multitrophic interactions. These relationships maintain biodiversity, improve nutrient cycling, and control pest populations, all of which support ecosystem stability. However, these networks are in danger of becoming unstable due to disturbances brought on by pollution, habitat loss, or climate change, which could have a domino effect on food security and biodiversity. Investigating the effects of global climate change on VOC emissions calls for immediate attention and action. Elevated atmospheric CO₂ levels, rising global temperatures, and shifting precipitation patterns are all known to influence the biosynthesis, release, and volatility of plant-emitted VOCs [7]. Moreover, air pollution, such as ozone or nitrogen oxides, can degrade or alter these VOCs, weakening their signalling effectiveness. This disruption can reduce pest control efficiency. These changes might then disturb the finely tuned multitrophic interactions that VOCs mediate—interactions between plants, insects, bacteria, and other organisms necessary for agricultural output and the balance of ecosystems.

The importance of comprehending and protecting these fragile networks is underscored by the fact that, for example, changed VOC emissions under changing climates may lessen their ability to draw in natural enemies or ward off pests, increasing ecological and agricultural vulnerabilities.

Future Directions

As our understanding of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) deepens, new frontiers in plant science and agricultural innovation continue to beckon. Long acknowledged for their functions in plant defence, communication, and ecological interactions, VOCs are now central to innovative strategies aiming to revolutionise pest control, pollination, and soil health. The potential for using VOCs in agriculture is enormous and still mostly unrealised. We can create plant varieties that naturally draw pollinators and beneficial insects like parasitoids or predators while also discouraging herbivores and disease vectors by improving and modifying the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in crops. By providing more ecologically friendly substitutes that complement natural systems, such tactics could drastically lessen our dependency on artificial chemical pesticides.

Another fascinating and fast advancing field of research is synthetic biology. Through genetic engineering, it is now possible to reprogram plants or associated microbes to produce specific, beneficial VOCs on demand. This innovation opens up the possibility of designing living systems tailored to address particular agricultural challenges—whether it be pest control, improved disease resistance, or enhanced nutrient uptake and cycling. For instance, while the induction of VOCs signals beneficial microbial colonisation could lead to more resilient plant-microbe interactions, the controlled release of repellent VOCs from engineered microbial communities in the rhizosphere could offer a new form of pest deterrent. By harmonising with ecological ideas and reducing environmental disturbance, these complex biological solutions have great potential to transform contemporary agriculture.

However, these advances must be considered within the broader context of a changing climate. Not only will knowledge of how climate-driven changes affect VOC dynamics help to forecast future ecological scenarios, but it will also enable the development of adaptive strategies protecting food production and biodiversity in a world fast changing.

As more and more plant-emitted volatiles are being explored, we find their central role in the complex chemical dance of nature. Plants use these molecules as their they choreograph complex ecological relationships, shaping interactions from insect behavior to microbial alliances. Deciphering this silent but significant communication helps us to design sustainable agricultural solutions to safeguard crops, improve ecosystem services, and lower our environmental impact. The hidden symphony of VOCs stands as a powerful testament to the ingenuity and resilience of plants, showcasing their extraordinary ability to adapt and thrive amid ever-evolving environmental challenges. As we continue to delve deeper into this field, we move closer to a future where agriculture and ecology are not in conflict but in concert, united by the invisible threads of chemical communication.

References

- Wei, J., Wang, L., Zhu, J., Zhang, S.,Nandi, O. I., & Kang, L. (2007). Plants attract parasitic wasps to defend themselves against insect pests by releasing hexenol. PLOS one, 2(9), e852.

- Rasmann, S., Köllner, T. G., Degenhardt, J., Hiltpold, I., Toepfer, S., Kuhlmann, U., Gershenzon, J., & Turlings, T. C. J. (2005). Recruitment of entomopathogenic nematodes by insect-damaged maize roots. Nature, 434(7034), 732–737. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03451Ninkovic

- Das, C. (2024). A Review on Understanding the Plant’s Secret Language for Communication and its Application. Haya Saudi J Life Sci, 9(1), 1-11.

- ul Hassan, M. N., Zainal, Z., & Ismail, I. (2015). Green leaf volatiles: biosynthesis, biological functions and their applications in biotechnology. Plant biotechnology journal, 13(6), 727-739.

- Sharifi, R., Jeon, J. S., & Ryu, C. M. (2022). Belowground plant–microbe communications via volatile compounds. Journal of Experimental Botany, 73(2), 463-486.

- James DG. Further field evaluation of synthetic herbivore-induced plant volatiles as attractants for beneficial insects. J Chem Ecol. 2005 Mar;31(3):481-95.

- Hartikainen, K. (2014). Effects of elevated temperature and/or ozone on leaf structural characteristics and volatile organic compound emissions of northern deciduous tree and crop species.