Insight Digest | Issue #4

In Insight Digest, we showcase the latest happenings in science research.Fast and precise atmospheric sensing over 100 km open path

Han, JJ., Zhong, W., Zhao, RC. et al. Nat. Photon. 18, 1195–1202 (2024) (University of Lille, France) Keywords: dual-comb spectroscopy, environmental sensing, frequency comb, spectroscopyDual comb spectroscopy (DCS) is a powerful optical sensing technique that leverages two laser frequency combs, to measure gas absorption with high speed and sensitivity. By precisely determining the absorption frequencies of the sample, across a broad spectral range, DCS can detect trace gases like carbon dioxide (CO\(_2\)) and water vapor (H\(_2\)O) in the atmosphere with sub-ppm precision. This makes it ideal for applications in climate science, especially relevant for air quality monitoring, greenhouse gas emissions tracking, etc.

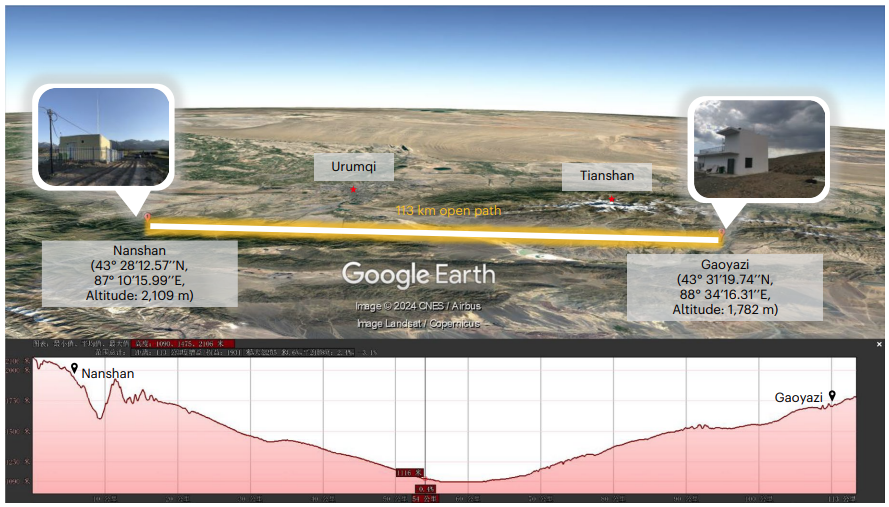

Traditionally, the reach of DCS when performed in open path has been limited to distances under 20 km due to significant signal loss and technical constraints, such as the need for highly reflective mirrors, high atmospheric turbulence, etc. However, last year, in a landmark advancement, researchers from the University of Science and Technology of China have now extended DCS to a staggering 113 km open-air horizontal path; nearly six times longer than previous records.

To achieve this, the team utilized a novel bistatic configuration, placing one frequency comb at each end of the path and transmitting light bidirectionally through the atmosphere without the need for reflectors. Each comb was synchronized to a rubidium atomic clock, acting as a local timing reference. The system incorporated high-power (1 W) optical frequency combs, stable telescopes, and real-time data acquisition to overcome atmospheric turbulence and extreme signal attenuation, going up to 83 dB.The experiment, conducted between two mountain sites in the Xinjiang, provice of China, viz. Nanshan and Gaoyazi, successfully measured absorption spectra of CO\(_2\) and H\(_2\)O over a 7 nm bandwidth and a frequency accuracy of 10 kHz. The system achieved CO\(_2\) detection sensitivities better than 2 ppm in just 5 minutes and below 0.6 ppm in 36 minutes; a remarkable performance for such a long-range setup.

This breakthrough not only validates DCS for ultra-long-range sensing but also opens a plethora of possibilities for a diverse set of technological advancements. A curious reader would ask, if one can perform DCS over 100 km path in the turbulent atmosphere, why not shoot it towards the sky? Can the dual comb reach the ionosphere (50 km) and get reflected with only the radio wave content? Can it lay the foundation for future satellite-ground dual comb links? Can it perform high-precision monitoring of greenhouse gases from geostationary orbits? I leave the numerous possibilities to the fancy of your imagination!

Tree rings unlock the sun's age old secrets

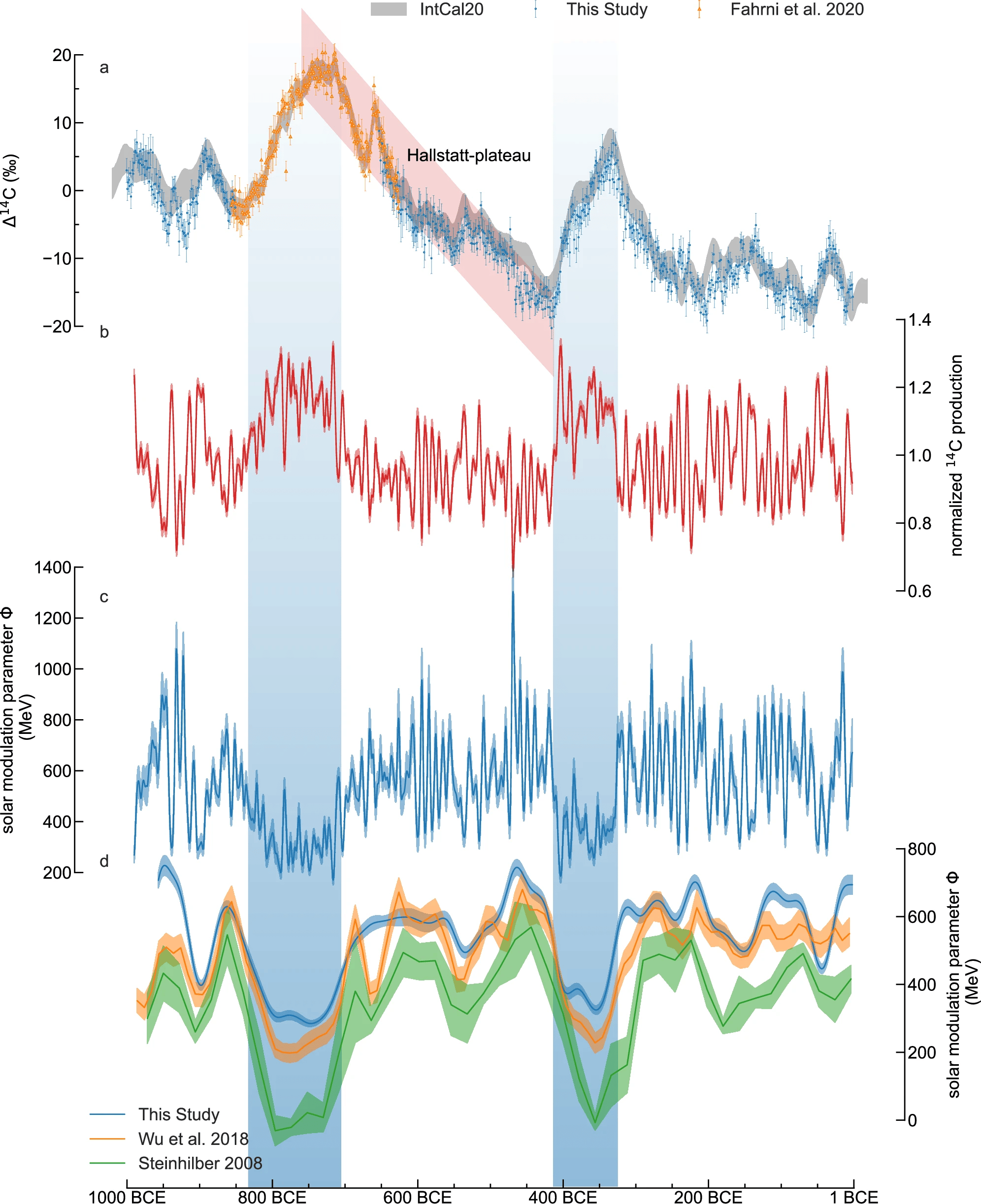

Brehm, N., Pearson, C.L., Christl, M. et al. Nat Commun 16, 406 (2025) (CESSI, IISER Kolkata) Keywords: Paleoclimatology, Dendrochronology, Solar Magnetic VariabiltyThe oldest telescopic observation of the sun is only four centuries old. Thanks to nature's silent archivists, it is possible to unveil how this star behaved multiple millennia ago. Tree rings are one such natural reservoir that keeps a record of the time. Cosmogenic isotope contents in old tree rings carry imprints of the terrestrial climate, which in turn is modulated by the sun's magnetic activity. A more magnetically active sun sweeps away galactic cosmic rays more vigorously. As a consequence, the production rate of radioactive isotopes in the earth’s atmosphere goes down. This results in a reduced amount of Carbon-14 deposition in the tree rings during the period of enhanced solar activity, and vice-versa. Recently, scientists have used precise dendrochronological techniques to retrieve the sun's magnetic behaviour during the first millennium BCE with an unprecedented resolution of annual time scale. They have successfully detected a strong decennial timescale signal in the isotope data, as expected from current understanding of the solar cycles. Besides, their analysis hints towards possible occurrences of two solar grand minimum episodes during this period. Solar grand minima are phases of prolonged magnetic quiescence on the sun. These findings have implications for a better understanding of solar-stellar magnetism.

How does Antarctic sea ice and circulation change fate of global CO\(_2\) levels

R. Ferrari,M.F. Jansen,J.F. Adkins,A. Burke,A.L. Stewart,& A.F. Thompson, Antarctic sea ice control on ocean circulation in present and glacial climates, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111 (24) 8753-8758 (2014) (22MS, IISER Kolkata) Keywords: Last glacial maxima, Carbon storage, Antarctic sea ice, Ocean Circulation, Isopycnal slopeOne of the key indicators of climate change is global warming — often discussed in academic circles and increasingly felt in daily life. A major driver of this warming is the rising concentration of atmospheric CO\(_2\) over recent decades. Oceans, which store about 90% of Earth’s carbon (combined oceanic, atmospheric, and terrestrial), play a vital role in regulating the carbon cycle and influencing climate.

During the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), around 25,000 to 20,000 years ago, Earth’s surface was 3–6 °C colder, atmospheric CO\(_2\) levels were 80–90 ppm lower, and vast ice sheets and sea ice covered the poles. Unlike the modern ocean, where Arctic-origin waters dominate and Antarctic waters occupy depths below 4 km, LGM oceans were filled with Antarctic-sourced waters up to 2 km, compressing northern water masses into shallower layers. This reorganization of deep water circulation reduced CO\(_2\) escape from the ocean surface and drew down atmospheric concentrations by 10–20 ppm.

Previously, these shifts were seen as a sum of individual physical changes — altered currents, increased layering, and less CO\(_2\) outgassing from the Southern Ocean. Several mechanisms contributed: an equatorward shift of the Southern Hemisphere westerlies weakened upwelling of deeper water, increased stratification acted like a lid on carbon venting, expanded sea ice reduced air-sea exchange, and reduced mixing between northern and southern waters limited carbon leakage.

Overturning circulation is a large-scale movement of ocean water where warmer, lighter surface waters move toward the poles, cool, and sink to form deep currents that eventually return to the surface. This circulation is driven by two main factors: flow along isopycnals (surfaces of equal density) and surface buoyancy flux — which reflects whether water in a region is becoming lighter (due to warming or precipitation) or denser (due to cooling, brine rejection, or evaporation). These isopycnals slope steeply at high latitudes, and a key one the 27.9 kg/m³ isopycnal which separates the shallow and deep overturning branches in the Southern Ocean.

In today’s climate, the sea ice edge stays close to Antarctica, and the isopycnal plunges below 2 km before reaching ocean basins. There, it intersects topography like ridges and seamounts, enhancing mixing and connecting the two branches into a single, figure-eight-like circulation. However, during the LGM, the summer sea ice line shifted northward by about 500 km. The isopycnal followed, shoaling above 2 km and avoiding major topography. Without significant mixing, the circulation split into two separate loops: deep Antarctic waters recirculated beneath the ice, while northern-sourced waters looped above. This vertical separation helped trap carbon in the deep ocean.

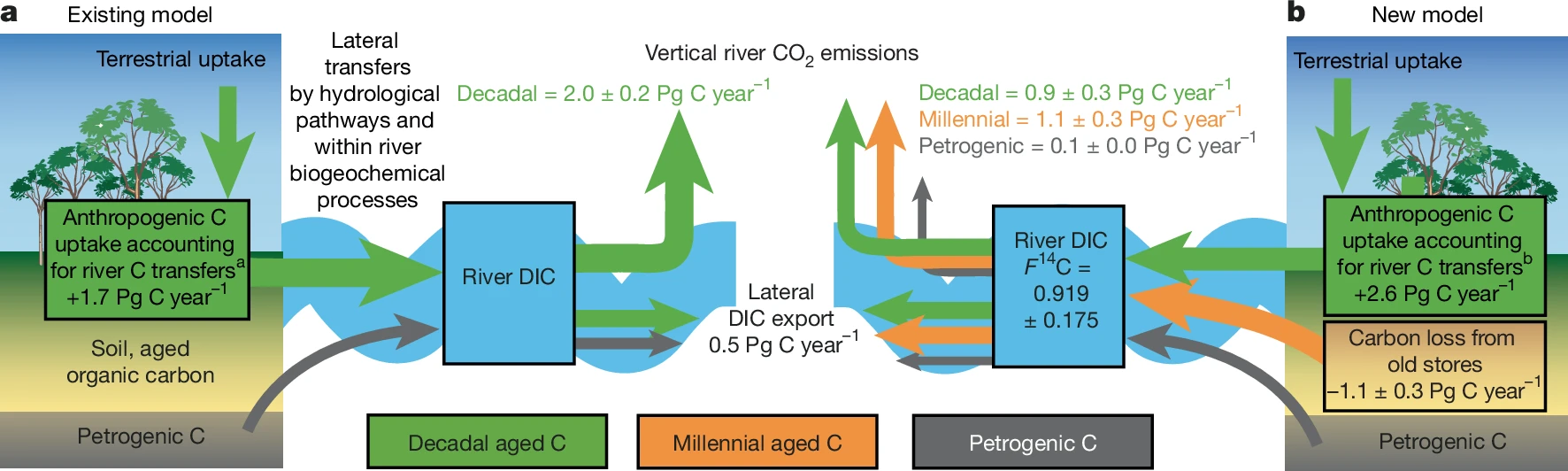

Old carbon routed from land to the atmosphere by global river systems

Dean, J.F., Coxon, G., Zheng, Y. et al. Old carbon routed from land to the atmosphere by global river systems. Nature 642, 105–111 (2025) (Department of Physical Sciences, IISER Kolkata) Keywords: River CO\(_2\) emissions, Radiocarbon dating, Global carbon cycleWe usually think of rivers as part of the modern carbon cycle — transporting carbon that plants have recently absorbed from the atmosphere. But this new study reveals that rivers also act as a hidden highway, carrying very old carbon — hundreds to thousands of years old — from land into the air.

Scientists examined over 1,100 samples from rivers all over the world, looking at the type of carbon gases (CO\(_2\) and CH\(_4\)) being released into the air. By measuring radiocarbon (a kind of natural carbon dating), they could determine how “old” the carbon was. Surprisingly, nearly 60% of river CO\(_2\) emissions were found to come from millennia-old carbon, not recent plant activity.

This “old” carbon comes from deep in the soil, sediments, and even from ancient rocks. Rain and groundwater erode and carry this carbon into rivers, which then release it into the atmosphere. The amount of old carbon released — around 1.2 billion tons per year — is nearly as much as all the carbon plants worldwide absorb from the atmosphere in a year.

Different factors affect how much old carbon a river releases. Rivers in areas with sedimentary rocks, like limestone, or those in high mountain regions, were more likely to release older carbon. Large rivers also showed older carbon emissions, which challenges the common belief that only small rivers are affected by old carbon sources.

These findings mean that current climate models and carbon budgets may be underestimating how much ancient carbon is being released. Old carbon, once locked in the earth, is now entering the modern carbon cycle — potentially speeding up climate change.

This study suggests we need to rethink how rivers fit into the global carbon puzzle. Rivers are not just channels for young, fresh carbon. They are also leaks for ancient carbon stores, and this has major implications for how we understand and manage Earth’s carbon balance.