Brain on Overload: Unlocking Hope for Rare Diseases Through Cellular Cleanup

When you think of waste management, the last thing that comes to mind is the human brain. Yet, deep within our cells, an intricate system works tirelessly to clear out damaged or unnecessary components, ensuring the smooth functioning of critical processes. But what happens when this cleanup system breaks down? For individuals with Mucopolysaccharidosis VII (MPS VII), a rare genetic disorder? This failure triggers a cascade of devastating events, culminating in severe brain damage and early death. In a landmark study, a team of scientists led by Professor Rupak Datta, from the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research Kolkata, has uncovered a crucial link between cellular waste accumulation and brain cell death in MPS VII[1].

When the Cell’s Janitors Go on Strike: Understanding MPS VII

Imagine a city where the waste disposal system suddenly breaks down. Trash piles up in the streets, clogging the pathways, polluting the air, and slowly choking life itself. This, in many ways, is what happens inside the bodies of people with Mucopolysaccharidosis VII (MPS VII), also known as Sly syndrome, a rare but profoundly impactful genetic disorder, affecting roughly 1 in 300,000 live births [3].

MPS VII is caused by mutations in the GUSB gene, which encodes β-glucuronidase (β-GUS), a crucial enzyme that helps break down large sugar molecules called glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) [4][5]. Without enough β-GUS, these GAGs build up inside cellular recycling centers known as lysosomes, leading to widespread cellular dysfunction and multi-systemic manifestations.

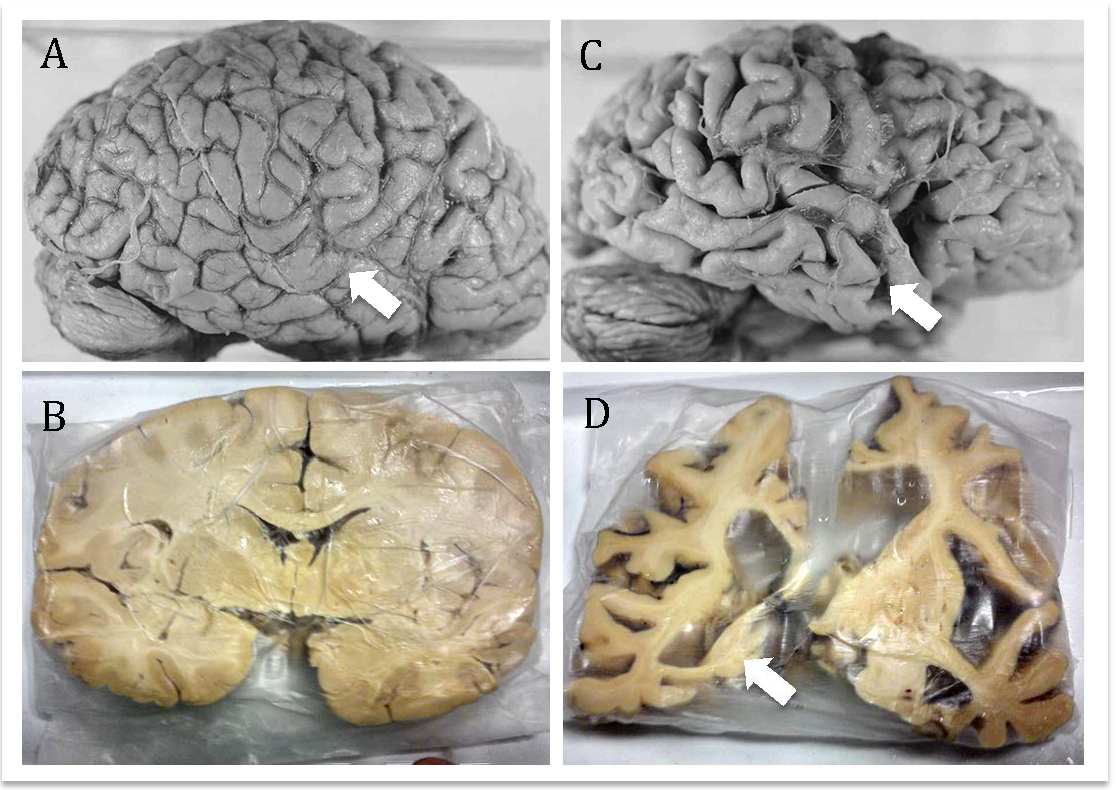

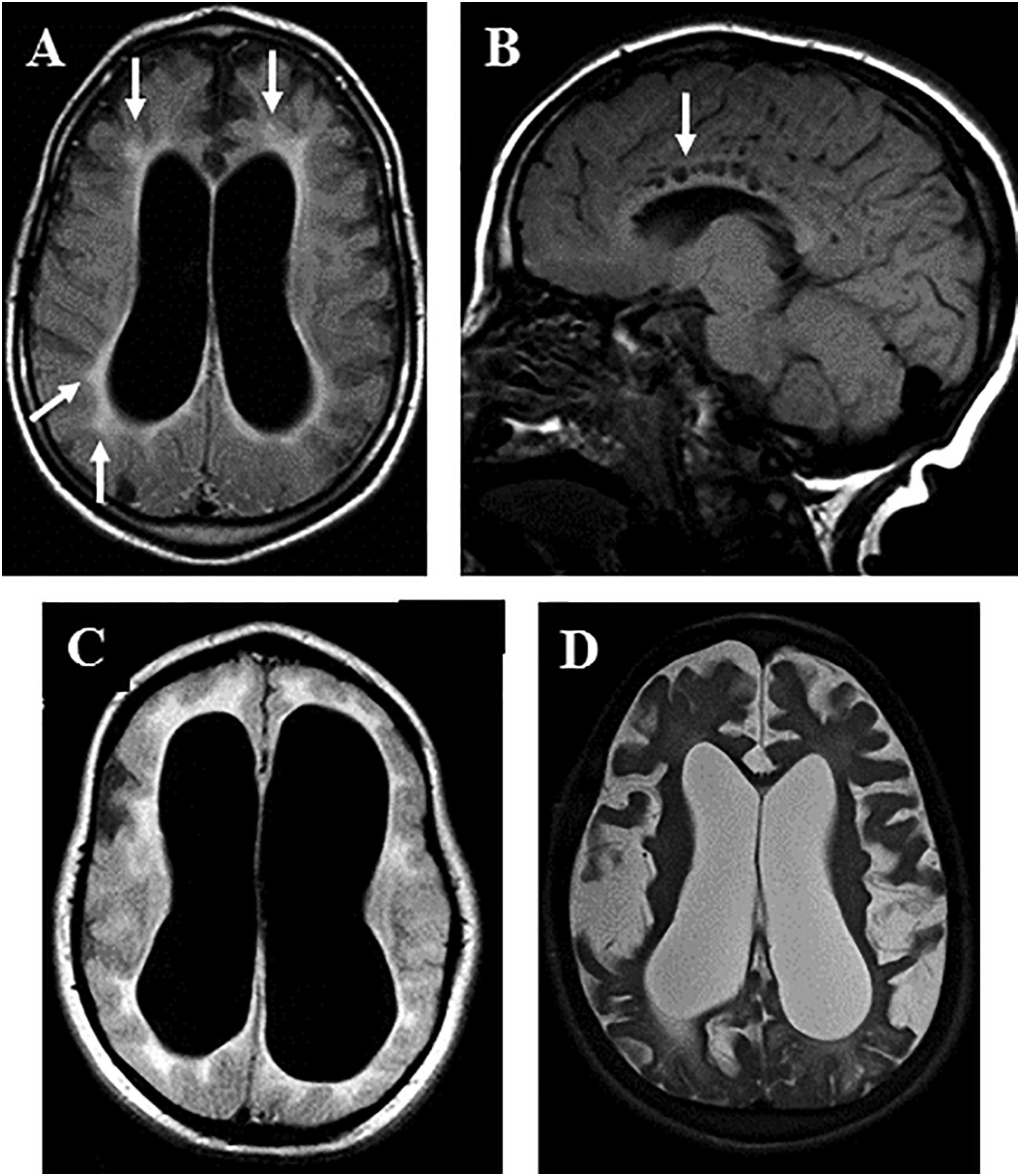

Children and adults with MPS VII often face skeletal deformities, enlarged liver and spleen (hepatosplenomegaly), heart problems, and, most heartbreakingly, progressive brain degeneration [6]. Neurological symptoms like cognitive decline, motor difficulties, and sensory deficits are stark reminders of how essential healthy lysosomal function is for maintaining brain health [7][8].

Today, enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) using vestronidase alfa offers hope by providing a functional version of the missing enzyme. However, there’s a catch: the brain remains largely out of reach. Like an impenetrable fortress, the blood-brain barrier prevents the therapeutic enzyme from entering, meaning neurological symptoms continue to worsen even under treatment [9][10]. Additionally, ERT is lifelong and extremely costly, posing serious challenges for patients and families.

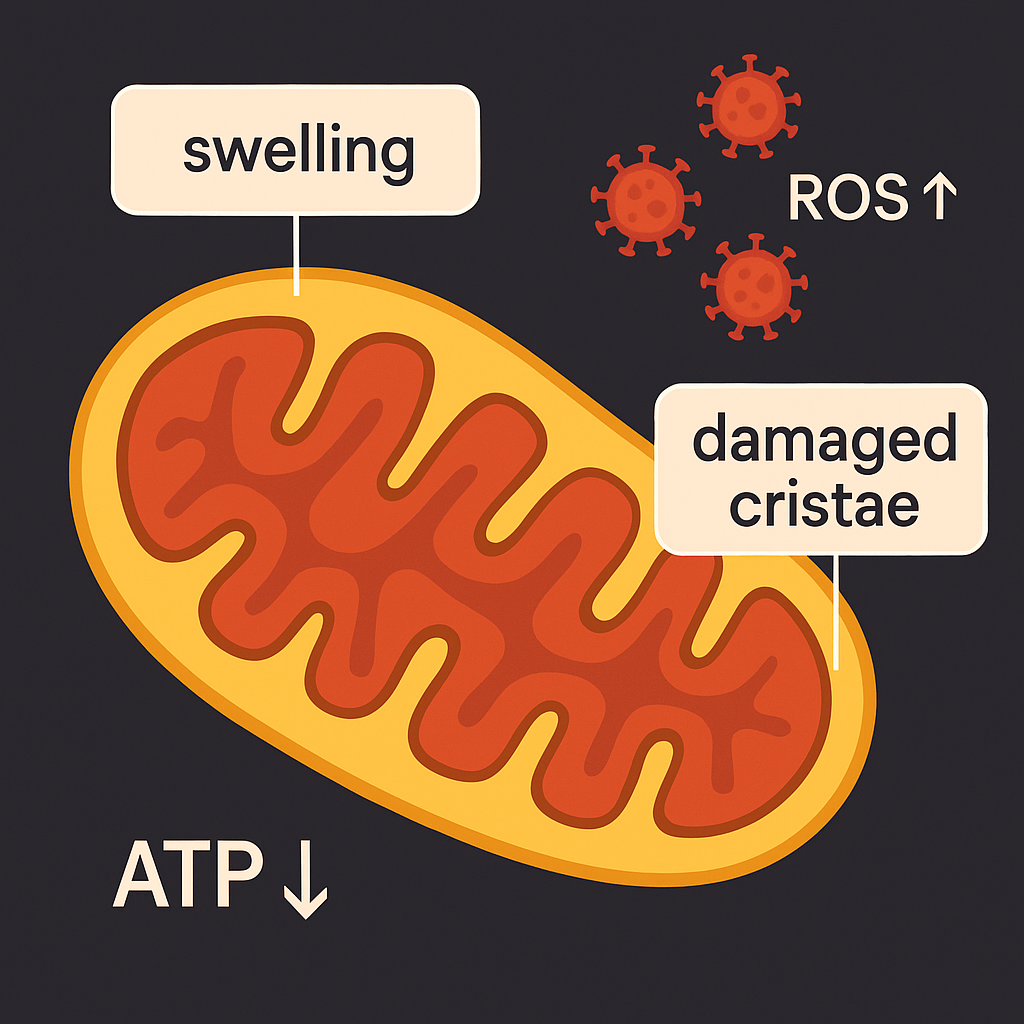

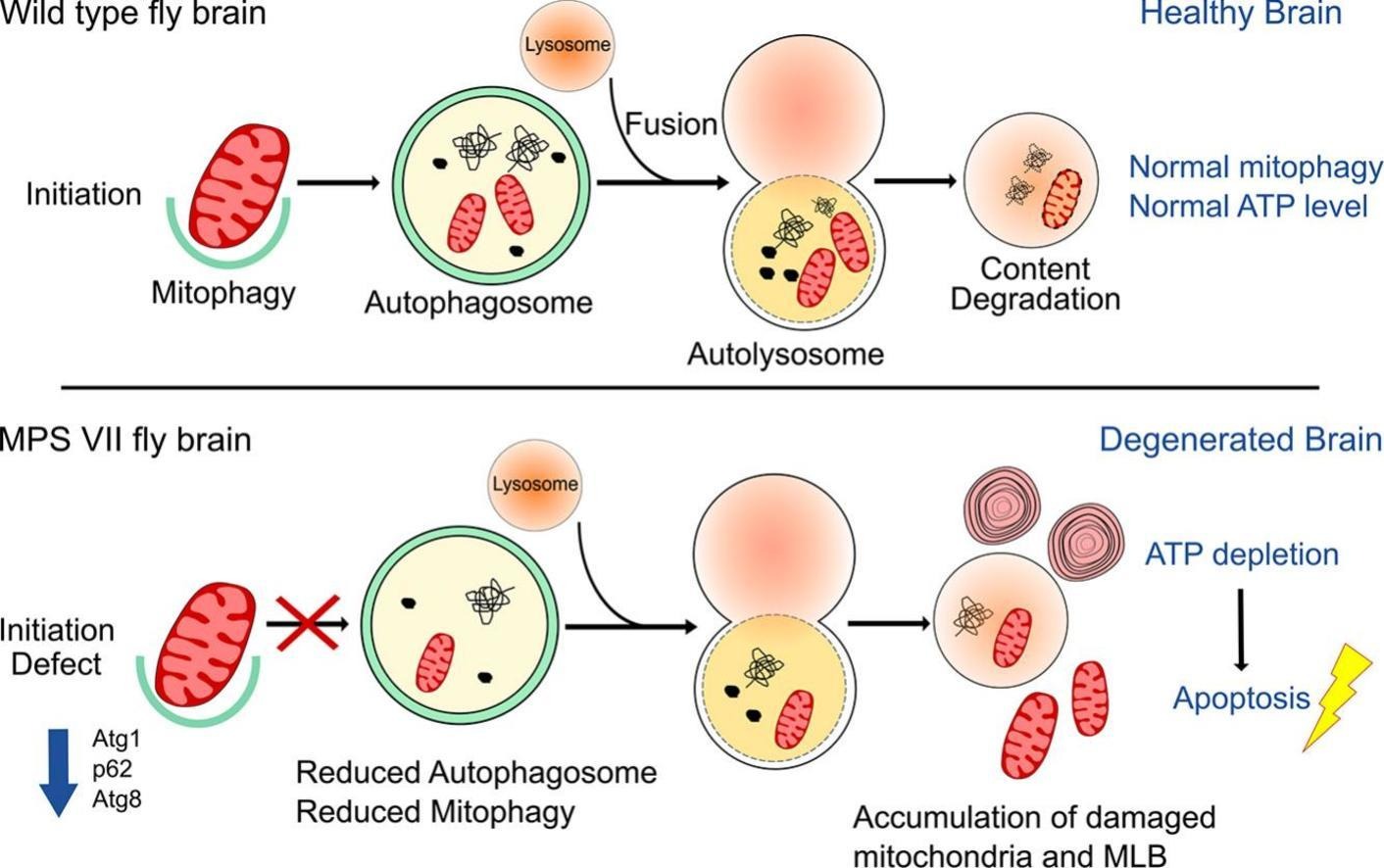

Recognizing these limitations, scientists have turned their attention deeper into the cell, looking for the root causes of brain cell death. Emerging research points toward disruptions in autophagy and mitophagy, the cell’s internal clean-up and recycling systems [10][11][12]. In healthy neurons, autophagy clears out damaged proteins, while mitophagy removes broken mitochondria (the energy powerhouses). When lysosomes fail, as in MPS VII, these processes are disrupted. Damaged mitochondria accumulate, producing excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS), draining cellular energy (ATP), and eventually leading to neuronal death, the true driving force behind the devastating brain symptoms [13][14].

Understanding these hidden cellular struggles opens the door to new therapeutic strategies, approaches that go beyond enzyme replacement to restore the brain’s self-cleaning systems and protect neurons from dying. It’s a shift from simply treating symptoms to targeting the core of the disease. For families facing MPS VII, each discovery brings a little more hope: hope that one day, the walls of the blood-brain barrier will be breached, and that both body and mind can be protected from the silent storms brewing within.

A Fly’s Eye View: Modelling MPS VII Neurodegeneration in Drosophila

Sometimes, big insights come from small wings. In the search for better ways to understand and treat brain degeneration in Mucopolysaccharidosis VII (MPS VII), researchers have turned to an unexpected model: the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster. It may seem like a leap, but the choice is far from arbitrary.

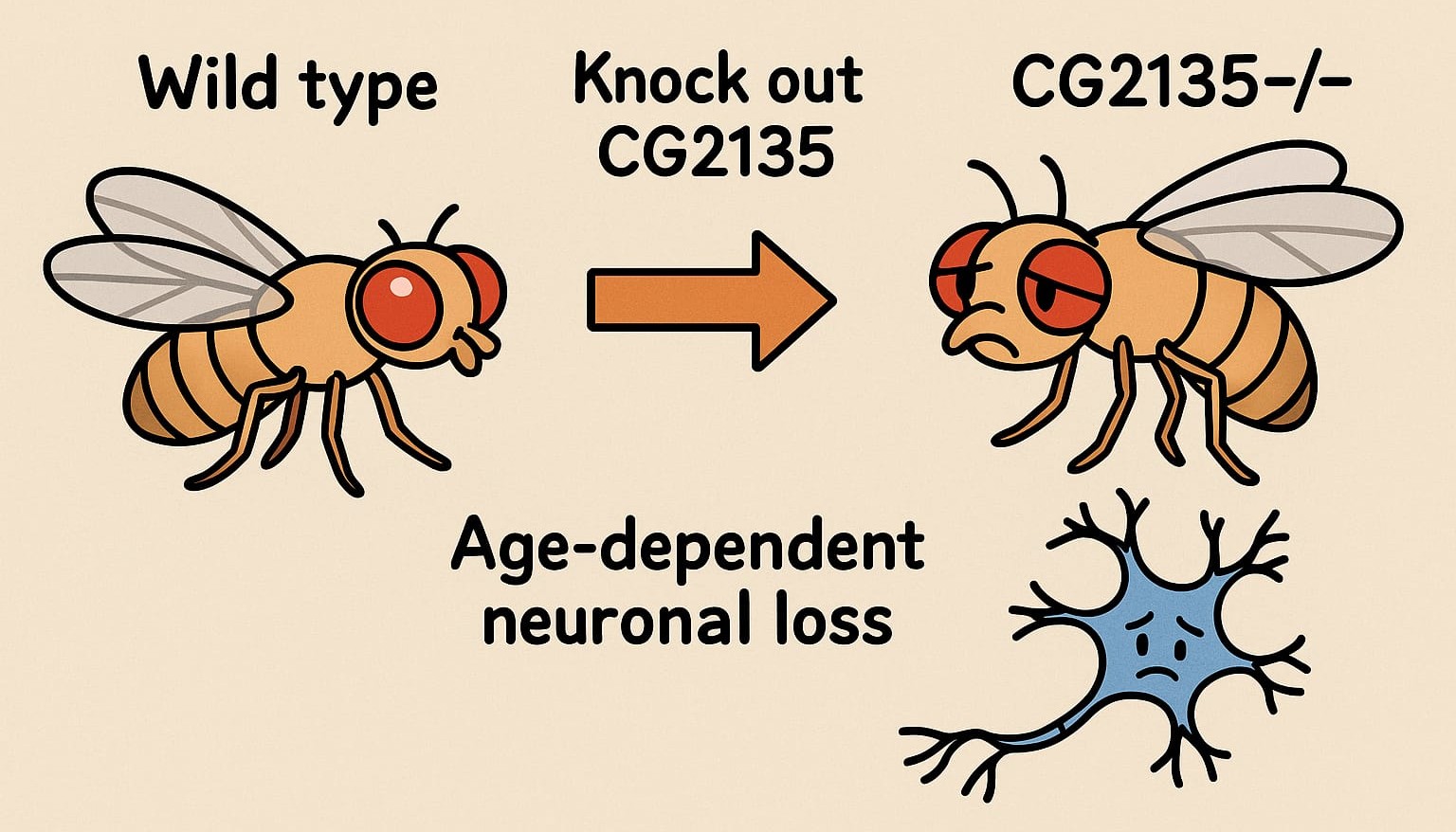

Drosophila offers a uniquely efficient and genetically powerful system for modeling human disease. Its dopaminergic neurons, brain cells responsible for movement and emotional regulation, are well-characterized and display many features seen in human neurodegenerative conditions. In this study, scientists knocked out the CG2135 gene, the fly equivalent of β-glucuronidase (β-GUS), which is defective in MPS VII. As a result, these mutant flies (CG2135-/-) exhibited age-dependent neuronal loss, mimicking the neurodegenerative decline observed in disorders like Parkinson’s disease.

Closer inspection revealed widespread mitochondrial damage, a known consequence of lysosomal dysfunction. These failing mitochondria were unable to be cleared effectively - a failure of mitophagy, the cell’s system for removing defective energy producers. Without it, oxidative stress increased, energy levels dropped, and neurons began to degenerate.

The strength of this model lies in its ability to recapitulate key disease features quickly and with genetic precision. But the very speed that makes Drosophila ideal for mechanistic insights also raises questions. Could its accelerated timeline of degeneration reflect the slow, complex pathology of human disease? Perhaps not exactly. Still, the conserved nature of autophagy, mitophagy, and mitochondrial regulation between flies and mammals provides a compelling reason to trust what we learn from these models.

By spotlighting how impaired lysosomal clearance and mitochondrial stress drive neuronal loss, this study lays the groundwork for future intervention - not just in flies, but potentially in humans as well.

The Mitochondrial Cleanup Crisis: How Impaired Mitophagy is Fueling Neurodegeneration

In the world of our cells, there’s an unsung hero—autophagy. Think of it as the cell’s janitorial service, working around the clock to clean up, recycle, and remove any unwanted materials, including damaged organelles. It’s a process that ensures cells stay healthy and functional, a vital part of maintaining cellular balance. But what happens when this cleanup crew goes on strike?

This question lies at the heart of a fascinating new study investigating MPS VII, a rare lysosomal storage disorder. MPS VII is marked by defective cellular recycling mechanisms, and the study reveals that the brain suffers significantly as a result. The culprit? Impaired mitophagy - the specialized form of autophagy that targets and clears damaged mitochondria, the powerhouse of the cell.

Imagine your body’s energy factories suddenly going dark. This is what happens in the MPS VII model, where defective mitochondria pile up in neurons, causing a dangerous ATP (energy) crisis. With energy running low, the neurons, unable to function properly, begin to die off in a process known as apoptosis. The result? Neurodegeneration, the kind of brain cell loss seen in Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases.

It’s a grim scenario, but there’s a hopeful twist. The researchers found that by enhancing mitophagy with resveratrol, a compound known for activating the SIRT1 pathway, mitochondrial clearance improved, and dopaminergic neurons were rescued from degeneration. This opens up a fascinating possibility: could we harness this approach to stop or slow down neurodegeneration in diseases like Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s?

Resveratrol and Autophagy Enhancement: More Than a Simple Fix

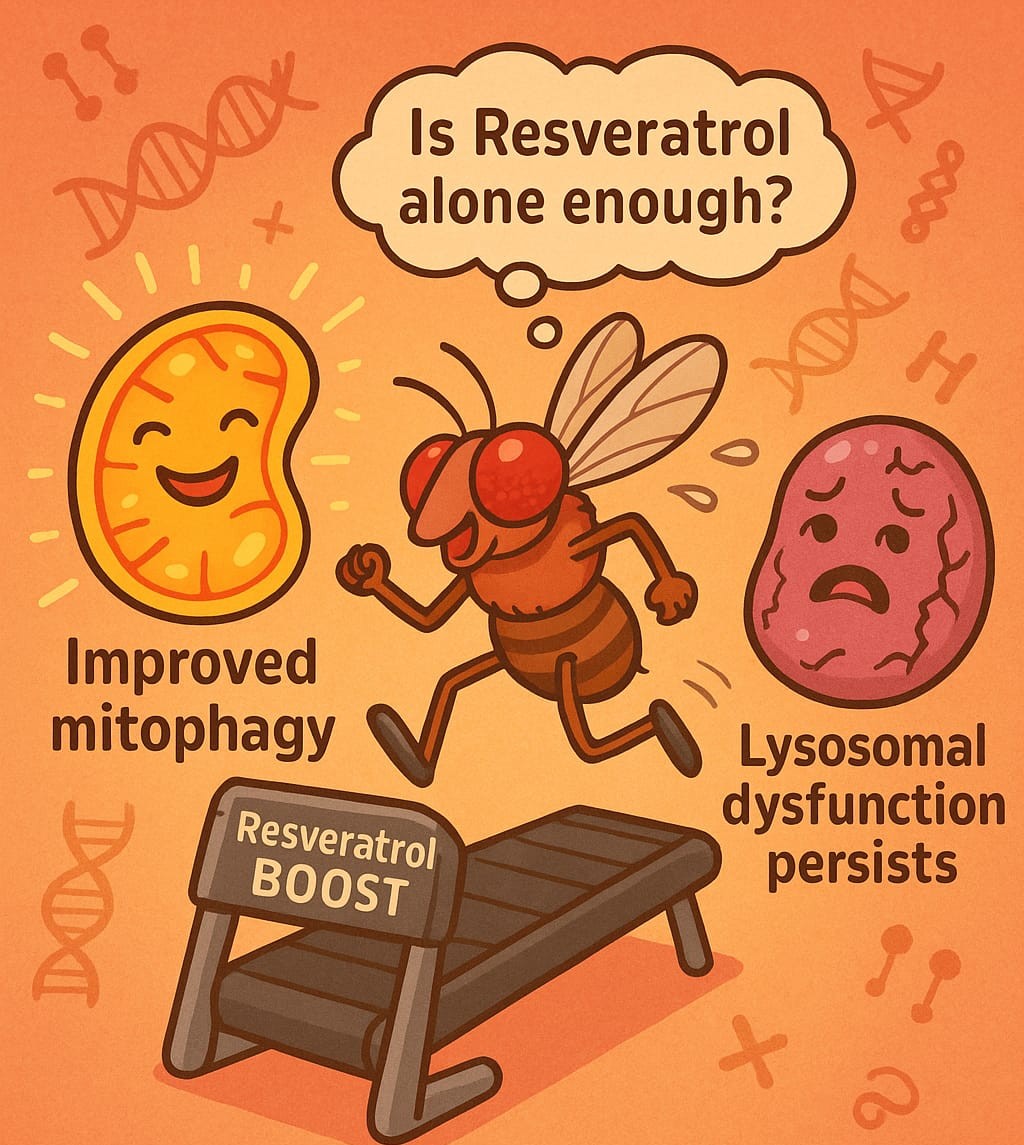

However, as promising as resveratrol seems, it’s important not to oversimplify the complexity of autophagy modulation. Resveratrol, a well-known SIRT1 activator, has been identified as a potential therapeutic agent for modulating autophagic flux and enhancing mitophagy. The study showed that resveratrol improved mitochondrial function and neuroprotection in Drosophila (fruit flies), a model organism for neurodegenerative diseases. Yet, while the results are promising, there’s a critical point to consider: could resveratrol alone be enough?

The research pointed out that while resveratrol enhanced mitochondrial clearance and improved neuronal survival, lysosomal function remained compromised. This suggests that enhancing autophagy through resveratrol alone might not fully address the underlying cause of MPS VII, which is rooted in enzyme deficiencies affecting lysosomal function. This raises an intriguing question: What if resveratrol’s effects could be amplified by targeting other epigenetic regulators or combining it with other treatments?

Could targeting additional sirtuins or histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors offer better outcomes? Moreover, a dual-pronged approach might be more effective. If autophagy can be enhanced while simultaneously restoring lysosomal function, perhaps through enzyme replacement therapies - this could offer a more comprehensive treatment strategy.

Autophagy Blockade: A Chicken-and-Egg Problem?

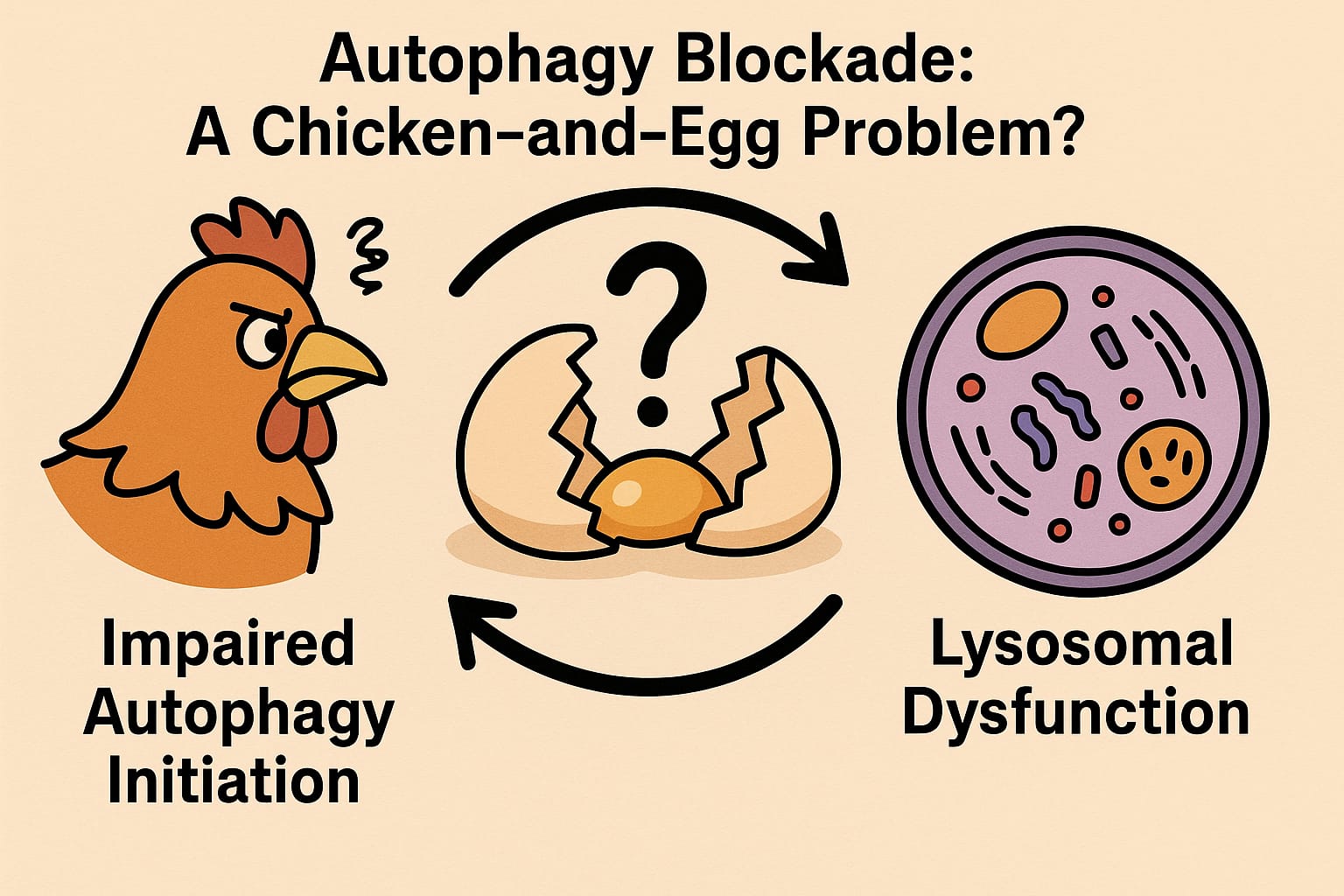

The downregulation of Atg1 (the Drosophila homolog of ULK1 in mammals) in the MPSVII model presents an intriguing paradox. Atg1 is crucial for initiating autophagy, and its reduced expression in this study suggests that lysosomal dysfunction might impair the initiation of autophagy. This raises the fundamental question: is the autophagy defect in MPSVII primarily due to lysosomal dysfunction, or is the failure of autophagy initiation contributing to the lysosomal burden? In other words, is this a feedback loop where one defect exacerbates the other?

The research provides compelling evidence that defective autophagic flux contributes to the accumulation of damaged mitochondria, but it does not yet answer the question of whether lysosomal dysfunction precedes or follows the autophagic defect. This “chicken-and-egg” scenario presents a fascinating puzzle for future research. Unraveling whether lysosomal dysfunction precedes autophagy impairment, or vice versa, could have profound implications for therapeutic approaches. For instance, if lysosomal dysfunction is the primary driver, then therapies focused on restoring lysosomal enzyme activity might alleviate both the lysosomal burden and the subsequent autophagic block. Alternatively, if autophagy defects are primary, then interventions aimed at restoring autophagic initiation could provide therapeutic benefit. Dissecting this feedback loop in greater detail is essential for developing more targeted therapeutic strategies for lysosomal storage diseases (LSDs) and other neurodegenerative diseases.

The Bigger Picture: Enhancing Mitophagy and Beyond

From a personal perspective, I believe that this research is a game-changer. Not only could it lead to new treatments for lysosomal storage disorders like MPS VII, but it could also offer a novel strategy for tackling other neurodegenerative diseases. The idea of improving mitochondrial quality control to reduce the build-up of damaged mitochondria could be the key to preventing neuronal death. But it’s also clear that to make a real impact, we need to think beyond a single pathway or treatment.

The future of neuroprotection might not lie in a single fix, but in a combination of therapies that target both upstream and downstream causes of disease. For example, combining autophagy enhancers with lysosomal enzyme replacements could offer a more robust therapeutic outcome, addressing both the root cause and the consequences of mitochondrial dysfunction.

As we continue to explore this concept, the future of neuroprotection looks a little brighter. With targeted therapies focused on enhancing mitophagy, we can turn the tide in the battle against neurodegeneration. After all, when it comes to keeping our cells - and our brains - healthy, sometimes a little cleanup goes a long way.

Broader Implications: Connecting the Dots to Other Neurodegenerative Disorders

While the study centers on MPSVII, the findings have far-reaching implications for understanding neurodegenerative diseases more broadly. Conditions such as Parkinson’s disease (PD), Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) share a common theme of defective autophagy and lysosomal dysfunction, which contributes to the accumulation of cellular waste, including damaged mitochondria. The research demonstrated that both mitochondrial dysfunction and autophagic blockade play crucial roles in the pathophysiology of MPSVII, reinforcing the idea that these pathways are central to a wide range of neurodegenerative disorders.

From my perspective, the study underscores the importance of viewing LSDs not in isolation, but as models for understanding common mechanisms of neurodegeneration. By shifting the focus from disease-specific pathways to shared cellular dysfunctions, such as impaired autophagy-lysosome pathways, we open the door for cross-disease therapeutic strategies. For instance, therapies that enhance mitochondrial quality control could not only benefit LSD patients but could potentially serve as treatments for a range of other neurodegenerative diseases characterized by similar mitochondrial dysfunction.

Concluding Thoughts: A Roadmap for Future Research

In conclusion, this research provides critical insights into the role of mitophagy in MPSVII and its broader implications for neurodegenerative diseases. The study’s results underscore the importance of defective autophagy and mitophagy in neuronal degeneration, showcasing both the value and the limitations of Drosophila as a model for human neurodegeneration. It raises important questions about the interplay between lysosomal dysfunction and autophagy initiation, as well as the potential for combination therapies that target both pathways. While Drosophila remains an invaluable tool in studying these processes, the next steps should be to validate these findings in mammalian models to better understand their translational potential.

Ultimately, the concept of enhancing cellular clearance mechanisms, whether through compounds like resveratrol or novel mitophagy-specific agents, holds promise for treating not only MPSVII but also a wide spectrum of neurodegenerative disorders. This study sets the stage for future research that could lead to more effective, targeted therapies for these devastating diseases.