Smart Moves: Temple Langurs Master the Art of Begging

In Dakshineswar, a popular tourist and religious site in Kolkata, primates like the Hanuman langurs are adapting in surprising ways. Once wild foragers, these temple-dwelling monkeys have learned to strategically beg from humans—using deliberate gestures to get food. A three-year study reveals their sophisticated tactics, with 81% success rate, showing how human interaction is reshaping primate behaviour in real time.

For many non-human primates (NHPs), human-modified habitats are no longer fringe territories—they’re home (1). In parts of Asia, where primates like macaques and langurs hold deep religious or cultural significance, humans have historically shared space with these animals. Out of devotion, curiosity, or simply habit, people feed them (2). But what may seem like a small act of kindness or devotion is quietly transforming how these animals behave.

Previous studies show that in human-dominated spaces, NHPs are shifting from foraging leaves and fruits in the wild to relying on processed, human-provided foods (3,4). For these synanthropes, the line between “wild” and “urban” has blurred. The result? A new generation of primates that doesn’t see humans as potential threats, but as reliable food providers. Over-habituation is no longer an exception—it’s the new norm (5) for these urban adapted NHPs.

Urban Adaptation and Emerging Behaviours

Across the urban-rural gradient, these primates are not just tolerating human presence—they’re thriving in it. Bonnet macaques in southern India make specific cooing calls to solicit food from passersby (6), while Balinese macaques have mastered the art of bartering stolen sunglasses in exchange for snacks (7). These examples aren’t just anecdotes. They’re signs of adaptation unfolding in real-time, shaped by human interaction. This study focuses on one such adaptation on another NHP – the Hanuman langurs (Semnopithecus entellus).

Fig 1. Dakshineswar Temple, it is a Hindu shrine and very popular Kolkata landmark. Built in the 19th-century, this temple is located on the banks of the Hooghly River.

Fig 1. Dakshineswar Temple, it is a Hindu shrine and very popular Kolkata landmark. Built in the 19th-century, this temple is located on the banks of the Hooghly River.

These striking black-faced monkeys, commonly seen around temples and residential neighbourhoods are revered as embodiments of the monkey god, Lord Hanuman. Owing to this religious significance, these langurs often receive generous offerings from temple-goers and devotees, increasing their interaction with humans (8). Hanuman langurs are folivorous colobines whose troop size generally ranges between 12-31. They live in harem system with most troops being uni-male multi-female in their demographic structure. They are found across India, with distribution ranging from Rajasthan to West Bengal (8). This study focuses on the Hanuman langurs of Dakshineswar, a temple and a popular tourist site located in West Bengal, India. Interestingly, they have developed a clever strategy. One that helps ensure the flow of food keeps coming their way. A strategy, that has not been previously reported for the Hanuman langurs till now (9).

| Begging Code | Behaviour |

|---|---|

| BGp | Bipedal begging |

| BGq | Quadrupedal begging |

| BGe | Begging by embracing legs |

| BGc | Begging by holding cloth |

| BGh | Begging by holding hands |

| BGa | Begging with aggression |

| PB | Passive begging |

Table 1. Correlation between begging events (successful and unsuccessful) and variables affecting the outcome: Postures (BGpi,BGc,BGe), Lifestage (Adult, Adult female and adult male) and food receiving sequence (Offer1 and Offer 2). *** stands for p-value < 0.001, ** stands for p-value < 0.01”,

Monkey see, monkey ask: Decoding their Strategy

In the heart of Dakshineswar ( Figure 1) , there lives a thriving troop of 31 langur individuals. Our team, curious about the behaviour of these langurs, began following the troop with a camcorder and notebook in hand. We observed them throughout the day for three years, splitting our time into three slots: morning (9 am to 12 pm), afternoon (12 pm to 3 pm), and evening (3 pm to 6 pm). As time went by, the langurs became used to our presence.

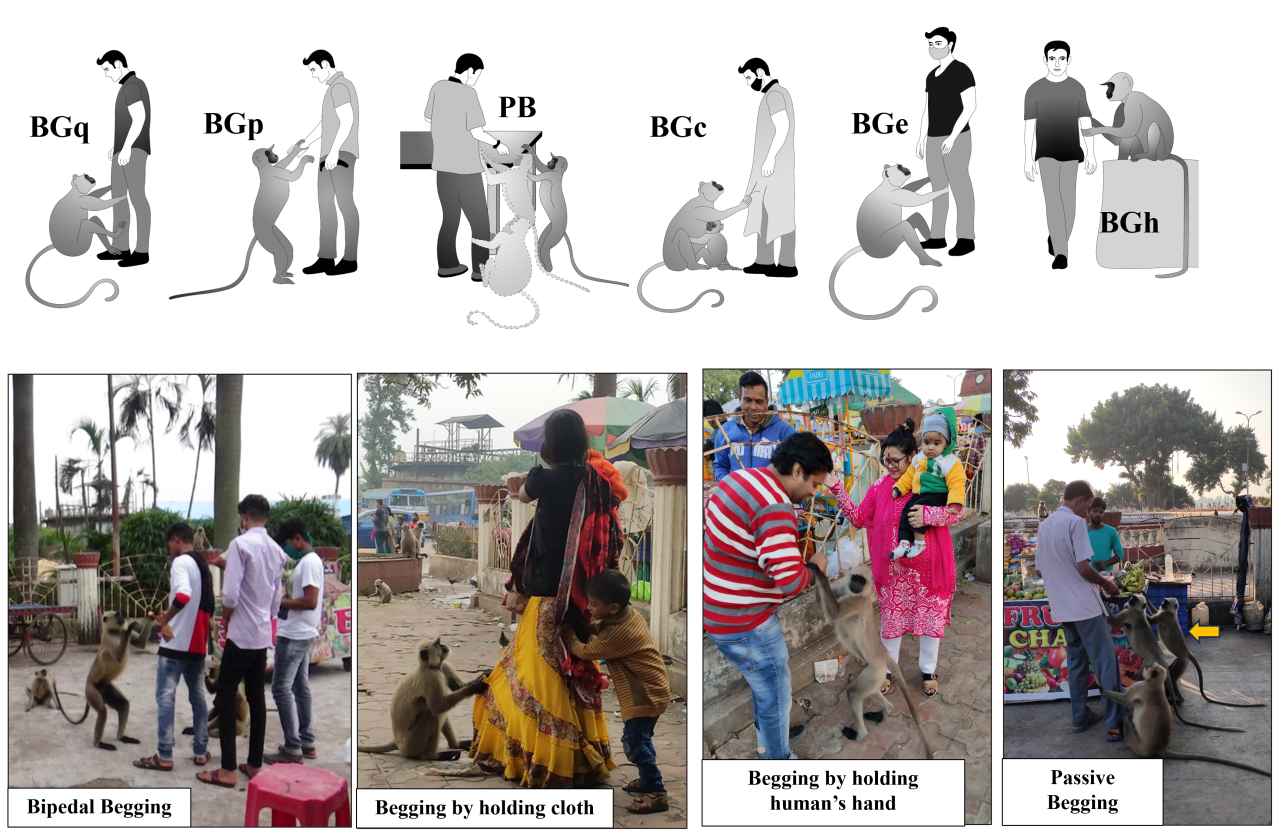

And during our observations, what we saw was more than just passive food acceptance. These langurs were asking. Not randomly or instinctively—but deliberately and repeatedly. Some stretched out a hand. Some stood upright on their hindlimbs. A few pulled people’s clothes gently. These weren’t clumsy bids for attention; they were patterned, strategic, and entirely directed at humans. A behaviour, that we did not observe in rest of our field sites (Howrah, Batanagar). We started noting them down carefully, eventually identifying seven distinct postures used to beg (Figure 2, Table 1).

One particular behaviour stood out. Near the temple’s food stalls, vendors often encouraged visitors to feed the monkeys. The langurs, it seemed, had learned to watch these interactions closely. As soon as someone approached a vendor, langurs would arrive near them and begin to beg—not aggressively, but deliberately, positioning themselves within reach, near both the vendor’s cart and the human. We called this behaviour Provocation-Initiated Begging, or BGpi.

| Variables | Successful Begging | Unsuccessful Begging |

|---|---|---|

| BGpi | 0.807*** | 0.517*** |

| BGc | 0.729*** | 0.777*** |

| BGe | 0.772*** | 0.355*** |

| Adult | 0.965*** | 0.76*** |

| Adult Female | 0.963*** | 0.758*** |

| Adult Male | 0.286*** | 0.234** |

| Offer 1 | 0.988*** | 0.564*** |

| Offer 2 | 0.325*** | 0.34*** |

Table 2. Correlation between begging events (successful and unsuccessful) and variables affecting the outcome: Postures (BGpi,BGc,BGe), Lifestage (Adult, Adult female and adult male) and food receiving sequence (Offer1 and Offer 2). *** stands for p-value < 0.001, ** stands for p-value < 0.01

Across our study period, we recorded a total of 1,293 begging events. Remarkably, 81% of these ended in the langur receiving food. These langurs weren’t just lucky. Over time, the langurs had refined their strategies, becoming more efficient. This might be because each food that was offered to them acted as a positive reinforcement that strengthened this behaviour.

Some begging gestures worked better than others. BGpi had the strongest positive correlation with success (r = 0.801***) (correlation values are presented as *** if the p-value is < 0.001). Other gestures, like simply extending a hand (BGe) or tugging at clothing (BGc), also showed strong correlations with successful outcomes. Interestingly, BGc—the most frequently used gesture—was also linked to unsuccessful outcomes (r = 0.77***). At first, this seemed odd. But it made sense: being the most commonly used (34%), BGc simply showed up in both outcomes more often.

Fig 2. (a) The seven begging postures employed by the Dakshineswar langurs. Art credit: Sourav Biswas. \ (b) Langur begging using postures as seen in Dakshineswar.

Fig 2. (a) The seven begging postures employed by the Dakshineswar langurs. Art credit: Sourav Biswas. \ (b) Langur begging using postures as seen in Dakshineswar.

Who Begs Best? Age, Sex, and Success Rates

We wanted to explore whether life stages played a role in begging outcome or not. Adult langurs, especially females, were far more successful in their begging attempts (Adults: r = 0.96***, adult females: r =0.96***) than sub adults (r = 0.5***) and juveniles (r = 0.06). Infants did not participate in begging behaviour. Interestingly, adult females had high correlation with both successful and unsuccessful events (r = 0.75***). That might be due to sheer numbers—there were more adult females in the troop, and thus more adult female beggars (Troop details: 31 consisting of 1 adult male, 9 adult females, 3 subadult, 12 juveniles and 6 infants). Another fascinating detail was the importance of the sequence in which the langurs received food items from nearby humans. We found that first offer—the first food item extended to a begging langur, had the highest correlation with success (r = 0.98***). However, correlation between successful begging event and begging sequence decreased as the begging sequence proceeded further to sequence two (r = 0.325***) and three (r = 0.061). While they were mostly quick to accept the first offering, there were instances where the langurs did not ‘like’ the first offering and went onto continue their begging gesture till they received their ‘preferred’ food item (Table 2).

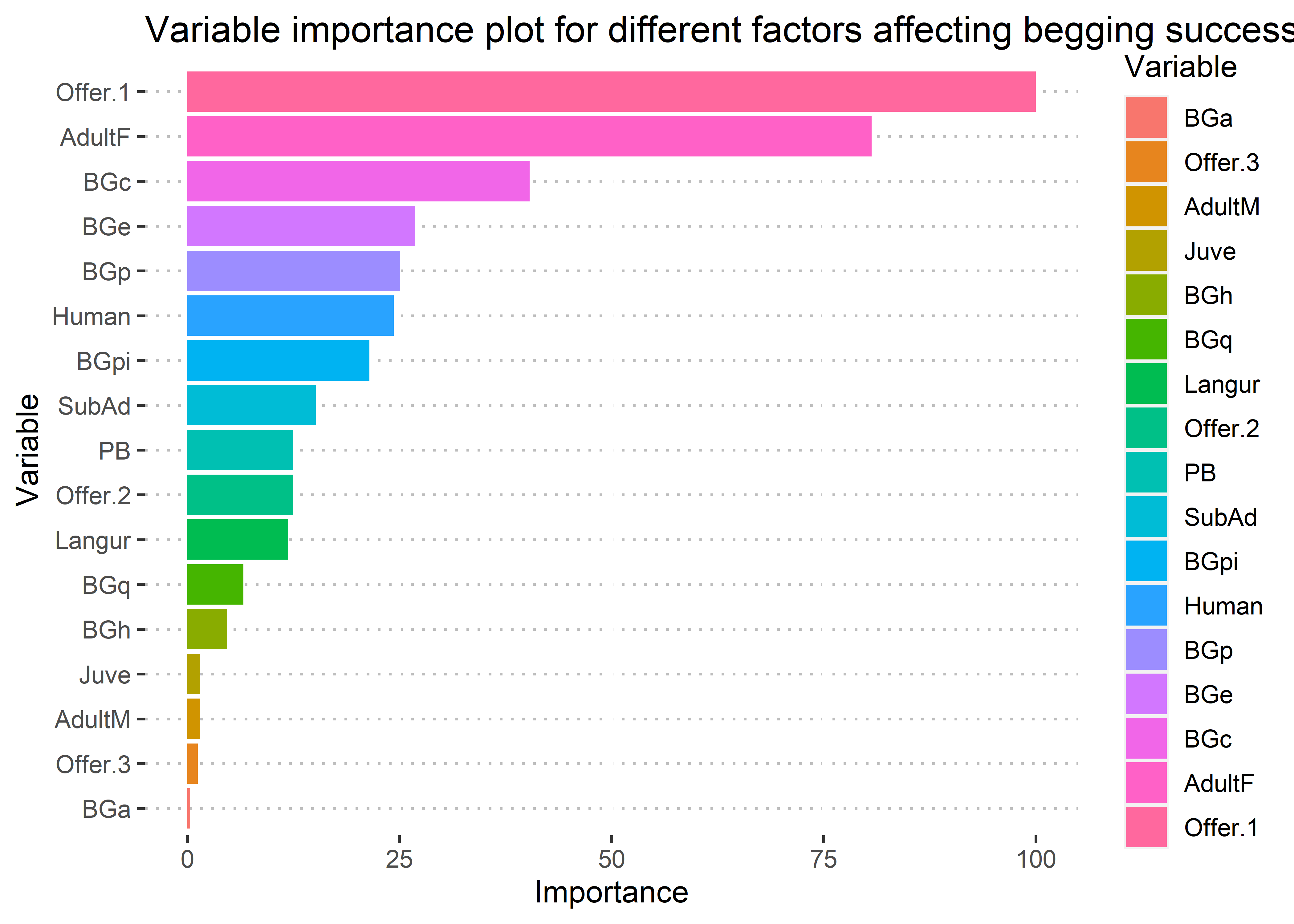

We also ran a random forest model to test the strength of our observations. It predicted begging success with 96.43% accuracy. The model confirmed what we saw in the field: first offer, adult female, and the BGc posture were among the most critical factors influencing successful outcomes (9) (Figure 3).

The langurs of Dakshineswar are more than just passive dwellers of an urban landscape. They have cultivated a unique approach to food—one that treats humans like part of their natural ecosystem. Through repeated, successful interactions, they’ve developed a gestural solicitation strategy, where certain postures or cues prompt people to feed them. Their ability to observe, adapt, and innovate reveal that they are responsive not just to food, but also to context, timing, and social cues.

A Future Shaped by Our Choices

As cities expand and wild spaces shrink, these interspecies encounters are becoming more frequent. What we feed, how we react, and the boundaries we set (or don’t) are all shaping how animals learn to coexist with us. Feeding a monkey near a temple might feel like a spiritual act, or a small moment of connection. But for the monkey, it’s a lesson—a pattern reinforced, a strategy confirmed. Over time, these lessons accumulate. What we’re seeing isn’t just survival. It’s adaptation.

Understanding this behaviour means accepting our role in it. The monkeys aren’t just evolving in a vacuum—they’re evolving with us. And in that shared space, the choices we make—what we feed, how we interact—are reshaping animal behaviour in real time.

Fig 3. Variable importance plot generated after running random forest model. Here the Y axis has all the variables affecting successful outcome of begging and X axis has the importance of these variables on bringing about a successful outcome. First receiving sequence (Offer 1), Adult females and BGc contributes heavily to the successful outcome of begging.

Fig 3. Variable importance plot generated after running random forest model. Here the Y axis has all the variables affecting successful outcome of begging and X axis has the importance of these variables on bringing about a successful outcome. First receiving sequence (Offer 1), Adult females and BGc contributes heavily to the successful outcome of begging.

References

- Dan Singh, S. (1969). Urban monkeys. Scientific American, 221(1), 108-115.

- Sengupta, A., & Radhakrishna, S. (2018). The hand that feeds the monkey: mutual influence of humans and rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) in the context of provisioning. International Journal of Primatology, 39(5), 817-830.

- McKinney, T. (2011). The effects of provisioning and crop‐raiding on the diet and foraging activities of human‐commensal white‐faced capuchins (Cebus capucinus). American Journal of Primatology, 73(5), 439-448.

- Dasgupta, D., Banerjee, A., Karar, R., Banerjee, D., Mitra, S., Sardar, P., ... & Paul, M. (2021). Altered food habits? Understanding the feeding preference of free-ranging gray langurs within an urban settlement. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 649027.

- Sugiyama, Y. (2015). Influence of provisioning on primate behavior and primate studies. Mammalia, 79(3), 255-265.

- Deshpande, A., Gupta, S., & Sinha, A. (2018). Intentional communication between wild bonnet macaques and humans. Scientific reports, 8(1), 5147.

- Brotcorne, F., Giraud, G., Gunst, N., Fuentes, A., Wandia, I. N., Beudels-Jamar, R. C., ... & Leca, J. B. (2017). Intergroup variation in robbing and bartering by long-tailed macaques at Uluwatu Temple (Bali, Indonesia). Primates, 58, 505-516.

- Vijayaraghavan, G., Tate, V., Gadre, V., & Trivedy, C. (2022). The role of religion in One Health. Lessons from the Hanuman langur (Semnopithecus entellus) and other human–non‐human primate interactions. American Journal of Primatology, 84(4-5), e23322.

- Dasgupta, D., Banerjee, A., Dutta, A., Mitra, S., Banerjee, D., Karar, R., ... & Paul, M. (2025). Decoding food solicitation techniques applied by free-ranging Hanuman langurs residing in an urban habitat. Animal Cognition, 28(1), 1-12.