Insight Digest | Issue #3

In Insight Digest, we showcase the latest happenings in science research.New Functions for an Old Protein: How Does RAS Drive Migration in Human Cells?

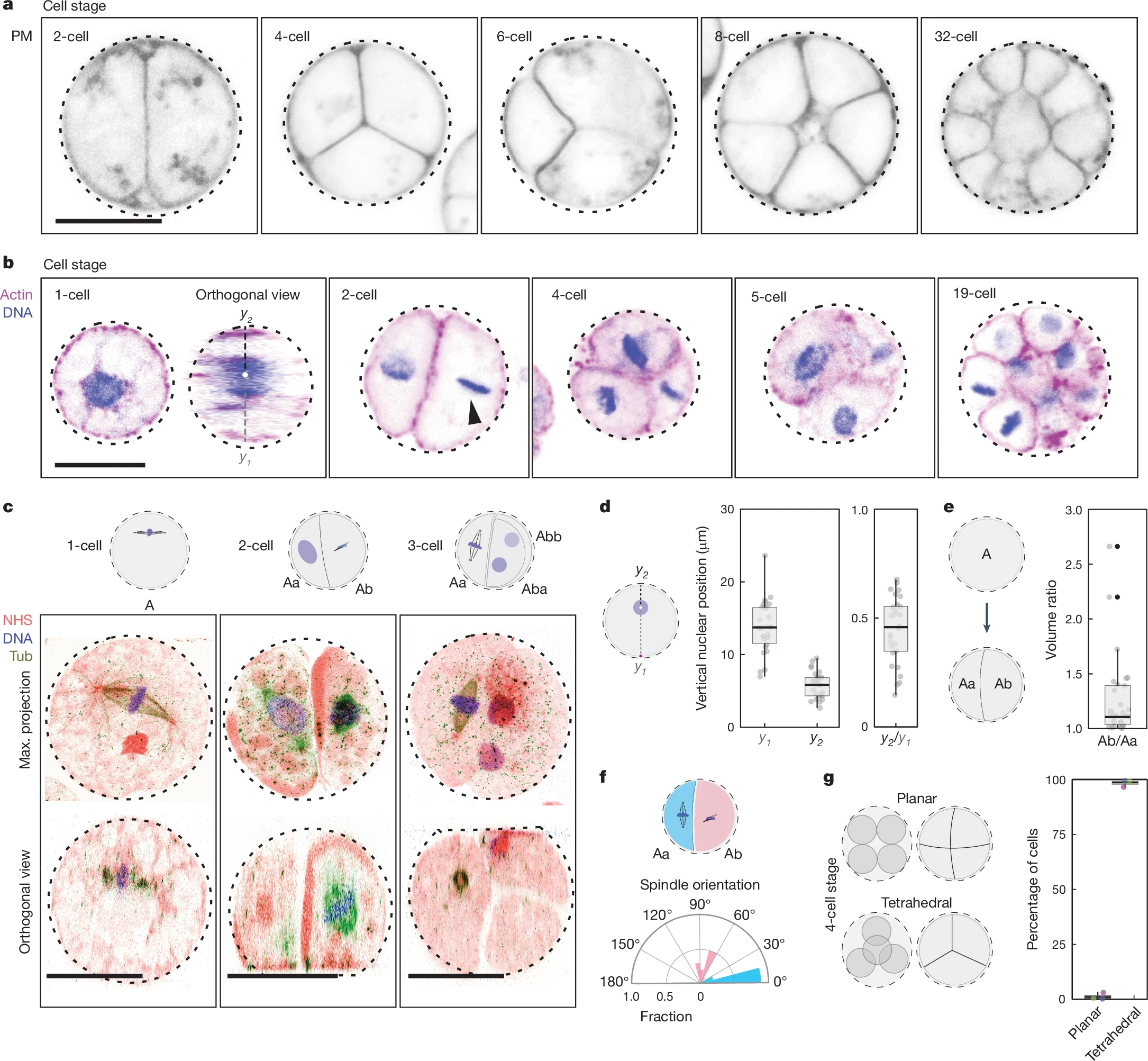

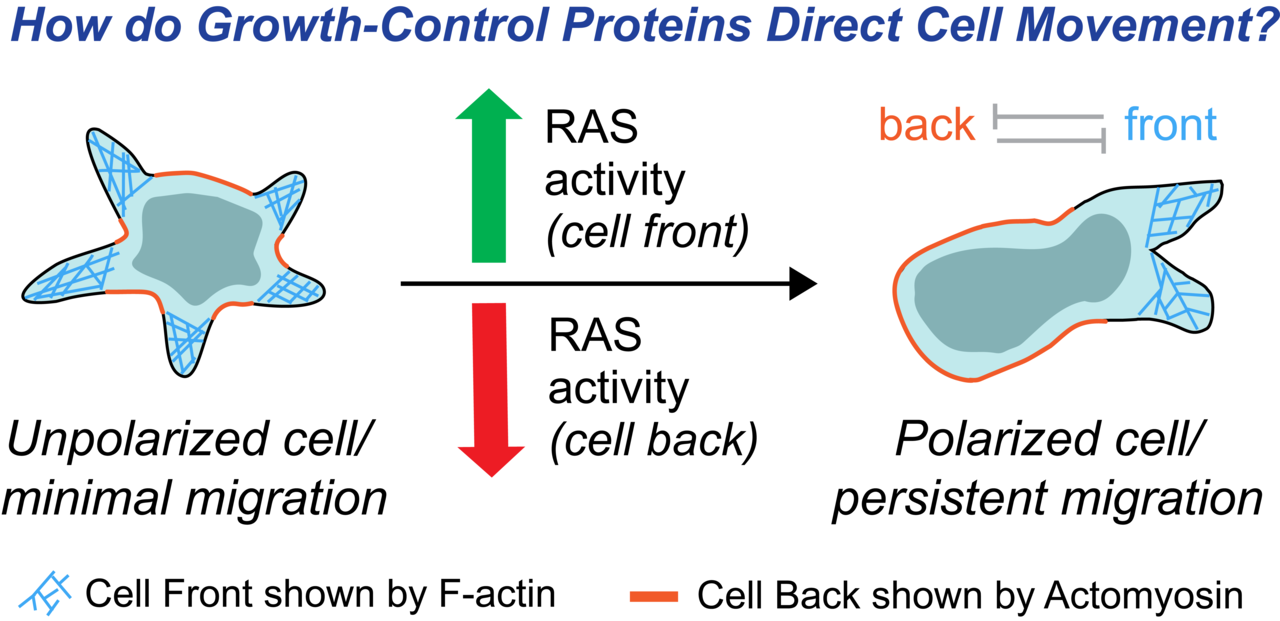

Pal, Dhiman Sankar et al. Developmental Cell, Volume 58, Issue 13, 1170 - 1188 (Department of Cell Biology and Center for Cell Dynamics, School of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA) Keywords: cancer, infection, optogenetics, signallingIn mammalian cells, directed migration is crucial for a multitude of physiological processes ranging from embryogenesis, cancer metastasis, to immune response. Although Ras and its downstream pathways are typically associated with longer-term growth control, our studies showed how the Ras-mTORC2-Akt growth-control axis steers leukocyte migration on a rapid timescale, independently of new gene or protein expression.

To this end, we designed blue-light controlled, cryptochrome-based dimerizers to abruptly and locally perturb Ras or Akt activity in human neutrophils and macrophages, bypassing the chemoattractant-sensing receptor/G-protein network. Within seconds of global recruitment of CAAX-deleted version of constitutively active Ras isoforms or a RasGEF, RasGRP4, initially quiescent cells spread and migrated rapidly. Thus, Ras proteins directly promote random motility. Furthermore, by activating Ras at the cell rear, new F-actin rich protrusions emerged locally, thereby reversing pre-existing polarity and steering sustained migration towards the light source. Interestingly, locally recruiting the crucial Ras-mTORC2 effector, Akt1 or Akt2, had similar effects.

Next, employing a RasGAP, RASAL3, we were interested to test the effects of reducing Ras in migrating cells. Globally or locally dampening Ras activity at cell fronts could extinguish protrusions and abolish polarity or migration, as expected. However, surprisingly, an acute reduction in Ras activity specifically at the cell back increased both polarity and random motility. Further experimentation showed that cell polarity can be achieved by suppressing Ras activity at the cell rear resulting in locally increased actomyosin contractility. These unexpected outcomes of attenuating Ras activity naturally had strong, context-dependent consequences for chemotaxis.

Our experimental results upended existing models of cell polarity, and a new computational model in which Ras levels control separate front and back feedback loops was proposed. Taken together, our unanticipated findings on cell polarity and migration have crucial implications for cancer treatment. While a target of intense interest for cancer therapy, Ras inhibition may not always be beneficial i.e., attempts to abrogate cell proliferation could force cells into a more polarized migratory state, thereby promoting metastasis. Minimally, our study suggests that a deeper understanding of the different roles of Ras activity is needed for developing therapeutic strategies.

Recyclable Bio-based Polyethylene-like Materials from Acceptor-less Dehydrogenative Polymerization of Bio-derived Diols and Catalyst-enabled Closed-loop Recycling

Liu, X., Hu, Z., Rettner, E.M. et al. Nat. Chem. 17, 500–506 (2025) (19MS, IISER Kolkata) Keywords: Acceptor-less Dehydrogenative Polymerization,, Catalytic Closed-loop Recycling,, DepolymerizationThe widespread applications of petroleum-derived polyolefins can be attributed to their favorable physicochemical properties and economic viability. However, the environmental footprint of polyolefins is increasingly concerning, as their mass-production, single-use-nature, and slow decomposition contribute to long-term ecological pollution. Chemical recycling of polyolefins, conventionally involves processes-pyrolysis or steam cracking resulting in significantly lower yields of constituting monomers even under high temperatures(~800 °C) or harsh conditions.

Effective resolution of this issue is contingent upon the development of polyethylene-like polymers that are both chemically recyclable and capable of replicating the key attributes of traditional polyolefins. Inclusion of ester or amide functionalities can operate as predetermined breaking sites within the polymer chain, enabling depolymerization at milder condition and yielding monomers suitable for re-polymerization.

In the aforementioned paper, Miyake and co-workers had reported the synthesis of bio-based polyethylene-like polymer-materials from linear and branched diols via Acceptor-less Dehydrogenative Polymerization(ADP), which display efficient depolymerization too, catalyzed with earth-abundant Manganese complex and exhibit highly tunable material properties. The crystallizable saturated linear monomer and unsaturated monomer were derived from fatty acids (plant-based oils), contributing high melting temperature(Tm) and modulus with its long linear methylene chains. The thiol-ene reactions with thiols, yielding high efficiency, enables the synthesis of branched monomers influencing polymer morphologies and thermomechanical properties. The authors had highlighted the manganese-based complex [Mn] as the most efficient catalyst for this Acceptor-less Dehydrogenative Polymerization and also depolymerization too, attaining high conversion and turnover number with the low catalyst loading and addition of suitable base.

The synthesized thermoplastic polymers demonstrated thermal properties comparable to commercial polyethylenes, with decomposition temperature of 395 °C and melting point(Tm). Increasing the content of branched co-monomers reduced crystallinity and modulus, ultimately leading to elastomeric behavior, while all compositions maintained high tensile strength(σUTS=16–27 MPa) and toughness(UT=100-180 MJ m−3), outstripping that of commercial plastics. Additionally, these PE-like materials showed excellent environmental stability and incorporating thioether or sulfone groups in the copolymers exhibited excellent adhesion to various surfaces-including stainless steel, aluminum and so on.

To overcome the traditional plastic recycling challenges, the authors introduced efficient chemical depolymerization of synthesized bio-based-PE-like polymers driven by hydrogen gas in the presence of mixed commercial plastics using the Mn-based catalyst[Mn], achieving high monomer recovery(91-99%), leaving other plastics impurities unaltered. The recovered monomers were successfully repolymerized through multiple cycles without loss of efficiency and stability, confirming the robustness of the closed-loop process. Furthermore, high-yield monomer recovery was achieved even in the presence of post-consumer plastics and at larger scales, highlighting the system’s practical and scalable recycling potential and route to sustainability.

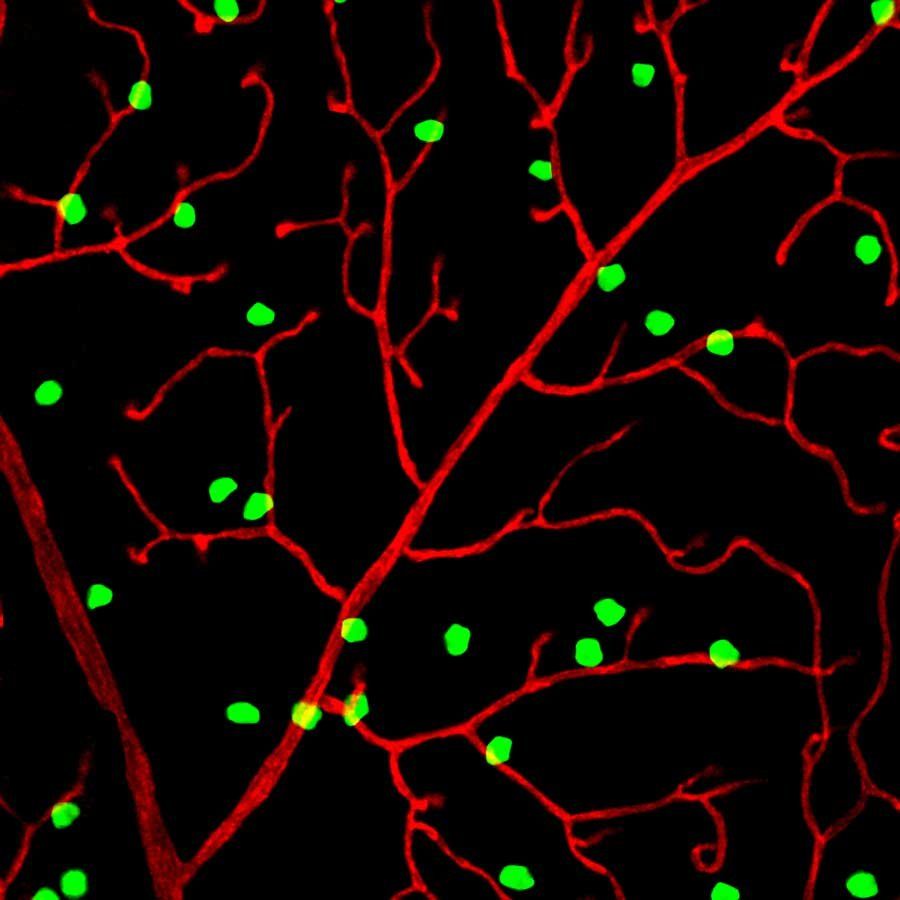

The Neuron With Its Own Brain

Toma K et al. Perivascular neurons instruct 3D vascular lattice formation via neurovascular contact. Cell. 2024 May 23. (23MS, IISER Kolkata) Keywords: Retinal-Neuron, contact-with-blood-vessels-3D latticeWe all know that the human brain is filled with neurons that direct our dreams and administer our body's organ functions effectively. But that's not all. Recent studies have found that a specific type of neuron in the eye plays a crucial role in vision—almost as if it has its own "eye and brain." Fascinating, right? For years, scientists have known that a network of blood vessels nourishes the retina (the posterior part of the eye), where light refracted from the lens forms an image. However, how this intricate structure develops remained a mystery. Now, researchers at UC San Francisco have discovered that a specific subset of retinal neurons, called perivascular neurons, directs the formation of the retina’s three-dimensional vascular lattice.

These researchers worked with newborn mice, whose eyes require several weeks to fully develop. Then they labeled the retinal neurons closest to blood vessels with a protein that glows bright green under ultraviolet light, allowing them to observe the lattice as it formed. These neurons establish direct contact with developing blood vessels through perisomatic endfeet(specialized neuronal structures that extend from the cell bodies of certain neurons) physically connect with surrounding blood vessels. This interaction guides the precise 3D lattice formation, which is essential for retinal health.

Perivascular neurons produce a mechanosensitive ion channel protein called PIEZO2, which enables them to sense contact with other cells. Now the absence of PIEZO2 disrupts these neurovascular interactions, leading to disorganized vascular structures, reduced capillary perfusion, and increased susceptibility to something called ischemic damage (tissue damage caused by lack of blood flow, eventually leading to cell death). In mice that could not produce PIEZO2, perivascular neurons failed to maintain contact with blood vessels, causing the vascular network to grow in a tangled, disorganized manner that disrupted blood flow. As a result, the surrounding nerve cells became oxygen-starved, deteriorated, and made the mice more vulnerable to stroke-like injuries.

By collaborating with developmental biologists, researchers could confirm that perivascular neurons also exist in the human retina, suggesting their importance in human vascular health. This discovery paves the way for new therapeutic approaches aimed at repairing or reorganizing damaged blood vessel networks, offering potential treatments for glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, and stroke. By exploring how neurons regulate vascular development, scientists can develop targeted therapies to maintain healthy blood flow, prevent neurodegeneration, and restore vision.

Intraspecific competition for a nest and its implication for the fitness of relocating ant colonies

Halder, E., Annagiri, S. Insect. Soc. 71, 431–440 (2024) (DBS, IISER-K) Keywords: Intraspecific competition, Colony relocation, Colony size, Tandem running, Brood theftThe study by Eshika Halder and Dr. S. Annagiri from Indian Institute of Science Education and Research Kolkata explores intraspecific competition in Diacamma indicum during colony relocation, a cooperative yet challenging process triggered by environmental stressors like habitat destruction, resource depletion, or predation. Unlike the commonly studied contexts of foraging and mating, this work focuses on competition for limited nesting sites, providing new insights into ant behavioral ecology and colony fitness.

The authors investigate how colony size affects competitive success, the nature of aggression during relocation, and how these interactions impact colony fitness. The experiments used both comparable-sized (CS) and non-comparable-sized (NCS) colonies in a controlled lab setup, simulating natural relocation conditions with two old nests and a single new nest. Behavioral data such as aggression, brood theft, and recruitment via tandem running were observed and statistically analyzed. Control groups (colonies relocating without competition and non- relocating colonies) helped assess the baseline levels of mortality and relocation efficiency.

Results show that colony size significantly influences success. In CS trials, one colony successfully relocated in 13 of 17 cases. In NCS trials, larger colonies dominated in 11 of 14 instances due to their numerical advantage in both aggression and recruitment. Smaller colonies struggled to manage both tasks simultaneously. Interestingly, colony mergers occurred in about 25% of trials, facilitated by cross-colony tandem running. These often led to the death of one gamergate, typically from the smaller colony.

Aggression was concentrated around critical zones like old and new nests, especially during the recruitment phase. Winning colonies were more strategic, involving fewer individuals in aggressive acts and reserving more for relocation. Brood theft was a notable behavior, primarily by larger colonies in NCS setups, enabling workforce expansion without reproductive cost.

The study highlights the high fitness costs of competition during relocation. Losing colonies exhibited mortality rates three to five times higher than controls, while even winners experienced elevated losses. These findings underscore the ecological risks associated with relocation, particularly when multiple colonies compete for limited resources. Overall, this research offers valuable insights into how social insects respond to ecological stress and competition. It contributes to our understanding of behavioral strategies, colony dynamics and has implications for conservation, especially under increasing environmental pressures.

Unlocking the Origins of Animal Multicellularity: A Close Relative Shows the Way

Olivetta, M., Bhickta, C., Chiaruttini, N. et al. Nature 635, 382–389 (2024) (Department of Physical Sciences, IISER-K) Keywords: multicellularity, evolutionary biology, cell differentiation, ichthyosporea, developmental biologyThrough high-resolution imaging and transcriptomic analysis, the researchers reveal that C. perkinsii undergoes a structured, palintomic (cleavage-like) cell division cycle, forming multicellular colonies with distinct cell types. This process mirrors aspects of early animal development, including spatial cell differentiation and gene regulation patterns similar to those in embryonic stages of sponges, cnidarians, and ctenophores. However, unlike true animals, C. perkinsii does not exhibit coordinated function among its differentiated cells, making it a potential intermediary form in evolutionary history.

Comparative transcriptomic analysis suggests that some of the genetic regulatory mechanisms underlying C. perkinsii's development align with those found in early-diverging metazoans, implying that the genetic toolkit for multicellularity predates the emergence of animals. These findings challenge the assumption that coordinated, spatial differentiation only evolved with true animal multicellularity. Instead, they support the idea that early unicellular relatives of animals may have already experimented with complex developmental strategies, long before animals emerged.

This study provides an evolutionary snapshot of the transition from unicellular to multicellular life, demonstrating that fundamental aspects of cell differentiation and developmental regulation were present in the common ancestors of animals and their unicellular relatives. Understanding how and why these mechanisms evolved could offer new insights into the origins of animal life itself.