Secret of the Wings: Nanostructures on a Dragonfly

It was the summer of 2017 when we visited Puri, a coastal city, in eastern India. On the fall of evening, the beach side road was bustling with tourists as my parents hopped from one shop to another, testing their price negotiation skills with the local shopkeepers. While my parents were busy in their shopping spree, I was having a fun time clicking pictures of some beautiful handcrafts in a souvenir shop, with my camera. While clicking one of those pictures, something interesting caught my attention. I found out that some of the items hanging near a bright light bulb outside the shop had become a playground for stray dragonflies. This species of dragonfly is also known as the globe skimmer (Pantala flavescens) due to its long migratory flights [1]. Around a hundred of them swirled in a chaotic yet mesmerizing dance, basking in the warmth of the incandescent bulb. It was quite serendipitous to discover such a gathering of one of my favorite insects, the dragonfly, while I had a camera in my hand. Before continuing with the story, I cannot resist a brief digression to explain why dragonflies are my favorites as an insect species.

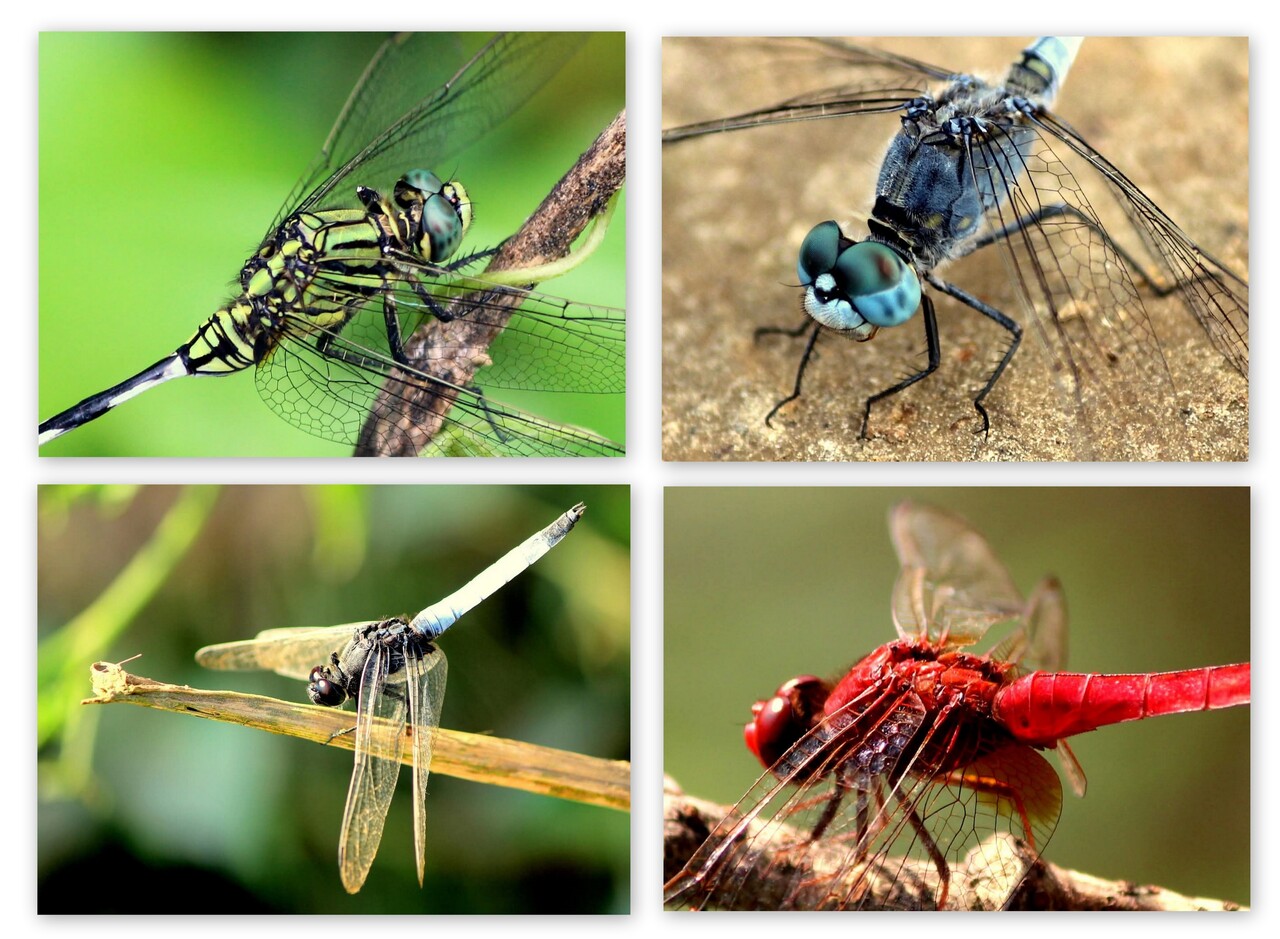

First of all, dragonflies are beautiful, with their large colorful compound eyes and their aerodynamic bodies, perfectly designed for flight (see some of my shots in Fig. 1). Additionally, dragonflies can control the flapping of their four wings independently, allowing them to take off vertically, fly in any direction—including forward, backward, right, left—and hover with unmatched precision. Moreover, while hunting, they can predict their prey’s trajectory and make fine adjustments to their own, in real-time all while airborne. The secrets of their flight dynamics, mate selection, predation, and visual information processing are all awe inspiring, making me feel the true ingenuity of Mother Nature.

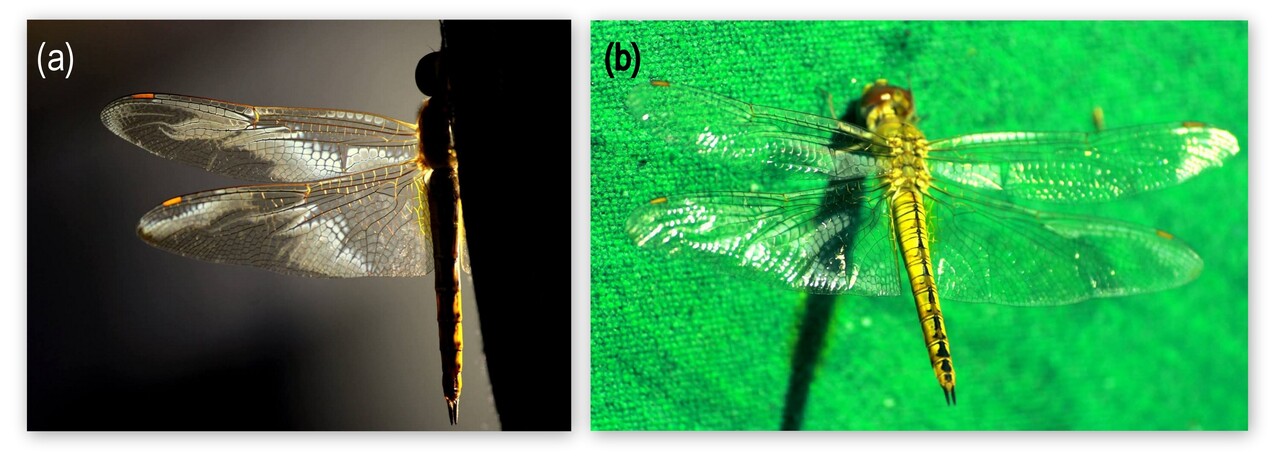

That evening, instantly I found myself capturing hundreds of close-up shots of these incredible insects. While taking these shots, I observed something very striking. In one of the shots, when I looked closely on the wings on the display screen of my camera, I noticed the insect’s wings had a faint opaque blueish pattern (see Fig. 2 (a)). It was quite surprising for me, because I always thought dragonflies had transparent wings. Then I had a look with my bare eyes at those insects. Yes, their wings were transparent to my naked eye. What, then, was that bluish pattern that my camera was displaying on the wings? Trying to answer this question I came across one of those feelings where I realized scientific research is no short of being in the shoes of a detective, trying to solve a case where the answer is apparently omnipresent, yet invisible to the common eye (pun intended). After thinking for a while on this, I had a closer look at some of the other images of dragonflies I captured the same day. I found out that in some of those images, the blue pattern was visible, while it was not present in the rest. For example, in the shot shown in Fig. 2 (b), we do not see the characteristic pattern clearly as seen in Fig 2 (a). In fact, the lower right wing in Fig. 2 (b) seems completely transparent. So, what was going on?

That evening, instantly I found myself capturing hundreds of close-up shots of these incredible insects. While taking these shots, I observed something very striking. In one of the shots, when I looked closely on the wings on the display screen of my camera, I noticed the insect’s wings had a faint opaque blueish pattern (see Fig. 2 (a)). It was quite surprising for me, because I always thought dragonflies had transparent wings. Then I had a look with my bare eyes at those insects. Yes, their wings were transparent to my naked eye. What, then, was that bluish pattern that my camera was displaying on the wings? Trying to answer this question I came across one of those feelings where I realized scientific research is no short of being in the shoes of a detective, trying to solve a case where the answer is apparently omnipresent, yet invisible to the common eye (pun intended). After thinking for a while on this, I had a closer look at some of the other images of dragonflies I captured the same day. I found out that in some of those images, the blue pattern was visible, while it was not present in the rest. For example, in the shot shown in Fig. 2 (b), we do not see the characteristic pattern clearly as seen in Fig 2 (a). In fact, the lower right wing in Fig. 2 (b) seems completely transparent. So, what was going on?

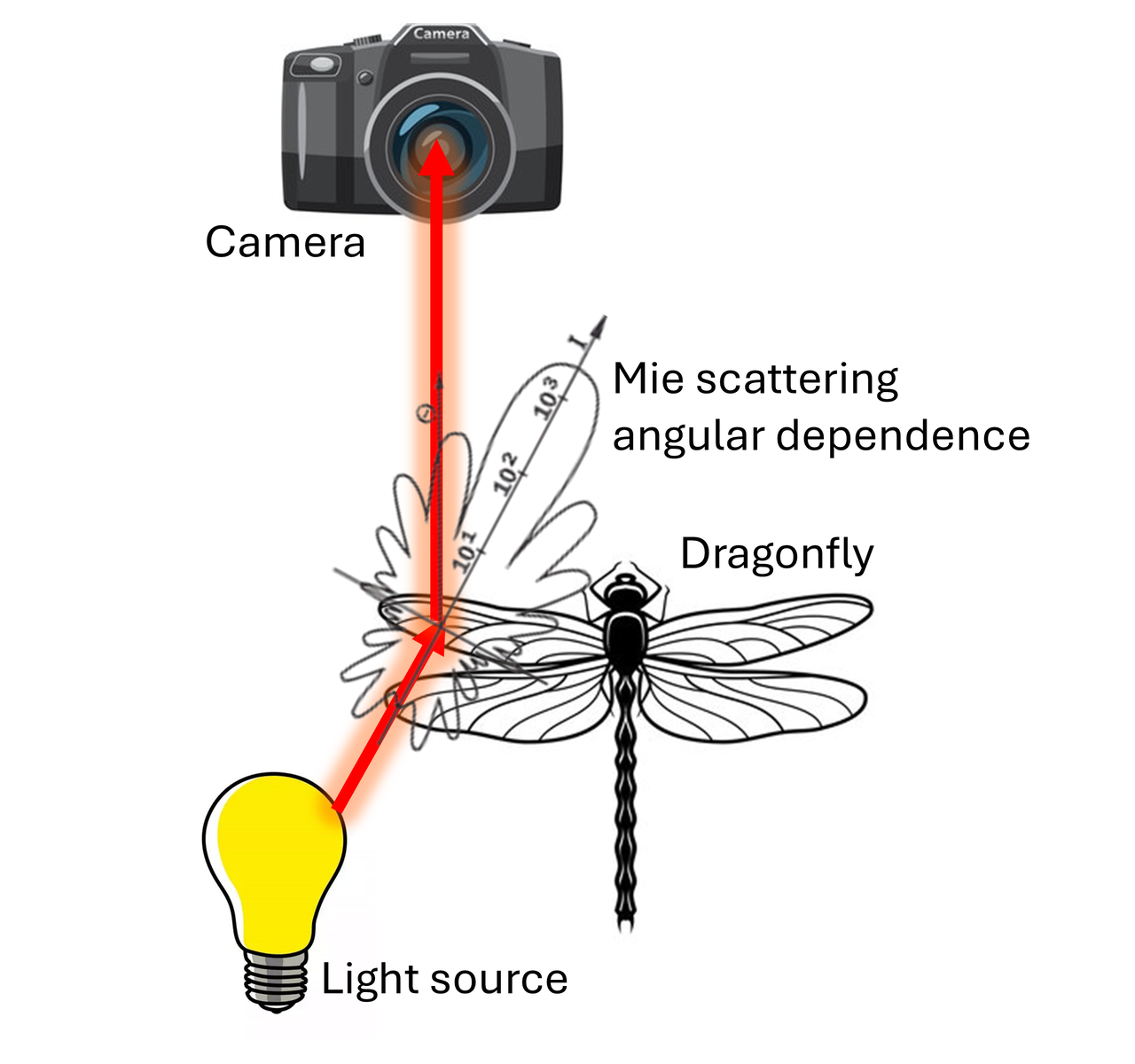

The first clue came when I noticed that the blueish pattern appeared when the line joining the light source and dragonfly’s wing was at certain angles to the line joining the wing and the camera lens (see Fig. 3). Does it ring a bell? The first thing that came to my mind was Mie scattering. Mie scattering describes how a small particle (typically dielectric) scatters incident light in different directions. The amount of scattering depends on the angle by which it is being scattered. In other words,when a small dielectric particle is illuminated by a beam of light, it scatters varying amounts of light at different angles. Also, an important aspect of Mie scattering is that it is efficient when the wavelength of the light is of the same order of magnitude as the size of the illuminated particle. Thus, if this blueish pattern on the dragonfly’s wing was due to some small structures present on the wings of the dragonfly, those structures must have been similar in size to the wavelength of the incoming light (visible spectrum : 400 nm to 700 nm). In this case, the incoming light was in the visible spectrum, with wavelength ranging from 400 nm to 700 nm. I immediately remembered, a professor at IISER Kolkata once told us in our classes about nanostructures found in the feathers of a peacock. He said that a peacock’s blue color does not come from pigment but instead results from light scattering by nanostructures. The same principle applies to some species of blue butterflies. Could the dragonfly’s wings be exhibiting a similar phenomenon? It was time to find out!

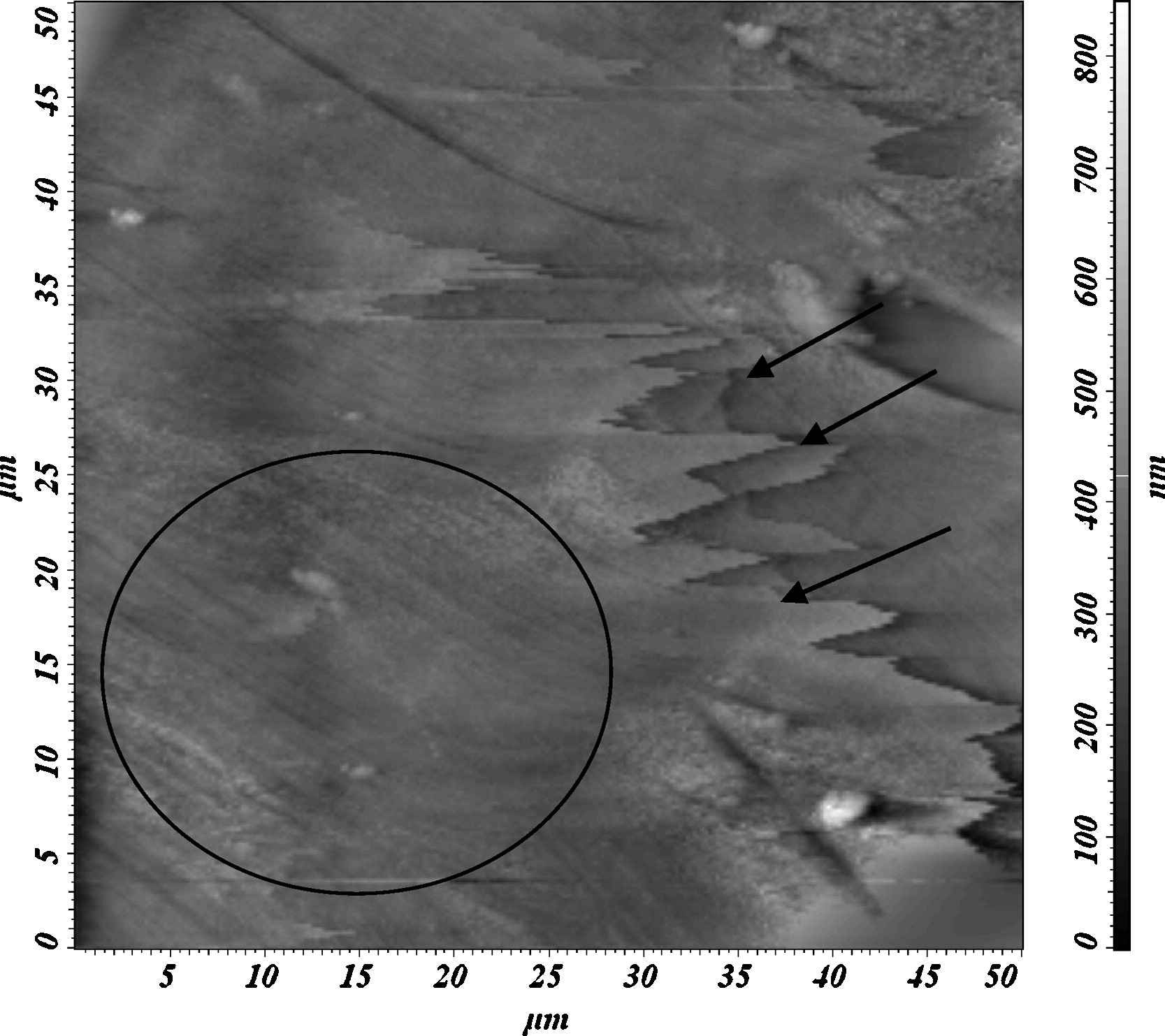

To investigate further, I turned to Google Scholar. I found a few papers that studied the structure of dragonfly wings and to my surprise I found ample evidence of the presence of nanostructures on their wings [2,3]! In fact, dragonfly wings contain nanoscale pillars, ridges, and pores composed of chitin, often combined with a thin wax coating. An example is shown in Fig. 4, where an atomic force microscopy image from [3] is shown, indicating multiple nanoscale layers (see arrows) and a “ripple wave morphology” (see circular region).

But then shouldn’t the dragonfly wings look blue all the time, like peacocks, rather than only from a particular angle? Maybe not. Here I remembered that those faint blue colors on the dragonfly’s wings were not conspicuously visible to my bare eyes. I could only see them through the camera. This might suggests that these colors were outside the visible range of my eyes but detectable by my camera.The Canon EOS 1200D camera I used has a CMOS sensor which is capable of detecting wavelengths from approximately 350 nm to 1000 nm, though infrared wavelengths are often filtered out optically. As a result, the camera can detect wavelengths slightly beyond the blue end of the visible spectrum. This suggests that the scattered light had a spectral signature just outside the visible range but still within the CMOS sensor’s detection band. Interestingly, a paper suggested that non-iridescent, angle-dependent color formation can occur at wavelengths between 350 nm and 500 nm due to electromagnetic resonances caused by the random aggregation of silica nanostructures [10]. However, whether this is the same mechanism for the dragonfly wings, needs to be verified through a detailed scientific investigation.

Another interesting question that came to my mind was about the visibility of these patterns to other dragonflies. It is true that humans cannot see shorter than 400 nm wavelength on the blue side, but what about the visible range of dragonflies? It turns out that dragonflies have a particularly sensitive vision in the wavelength range of 300 nm to 500 nm [4,5], and body and wing colours carry important visual cues influencing their behaviour [5]. Which means one dragonfly should be able to see the patterns on another one. Perhaps this is why they were hovering around the bright light source, where they can see those structures in its aesthetic eminence. Or maybe those nanostructures play a role in their mate selection?

In fact, research on the structural properties of the wings of a dragonfly witnessed a boom in the past decade. The wings’ nanostructures revealed anti-bacterial properties [6,7], opening potential application avenues in biofilm design for medical implants [8] or even in the food processing industry [9]. In a world of emerging technologies, I strongly believe in the potential of the dragonflies to inspire the next generation of biomimetic innovations.