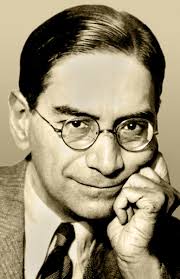

In Conversation with Prof. Probal Chaudhuri

“I believe science should be pursued out of passion, not for fame”, Manish and Swarnendu spent some time with Prof. Probal Chaudhuri, winner of Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar Award, as they revisited the pathways of the Indian Statistical Institute and the University of California, Berkeley, reflecting on his academic journey of last 40 years.

Manish Behera (MB): Good afternoon, Sir. Today, my friend, Swarnendu Saha, and I, Manish Behera, are here representing Team Inscight. We are truly honored to have the opportunity to engage with you.

To begin, we would like to ask you a question regarding your academic journey. As you know, the field of mathematics is vast and diverse. What specifically inspired you to pursue statistics as a career, and what was it about this discipline that appealed to you over other branches of mathematics?

Probal Chaudhuri (PC): Well, the specific reason I chose statistics actually goes back to after high school. Back then, for science students, the main options were engineering or medicine. And, in those days, a lot of my classmates who did well in high school ended up pursuing physics or chemistry honours, especially in places like Presidency College. A lot of them did really well later on.

I, on the other hand, had an interest in maths, and I was exposed to some basic probability problems early on, which really sparked my curiosity. Around that time, I found out that the Indian Statistical Institute (ISI) offered a course for undergraduates, and that was one of the few programs that offered scholarships. So, that caught my attention. It seemed like a great opportunity to pursue something I liked while also getting financial support.

Another reason was that, at the time, most engineering programmes were residential, meaning you had to stay on campus. But I preferred to stay at home while studying. So, the fact that ISI was a non-residential program was an added bonus for me.

In the end, it wasn’t just one thing that influenced my decision, it was a mix of factors. I didn’t have a super strong, singular passion for statistics at the time; it was more about the opportunities available and a series of practical considerations that led me down this path.

MB: I believe you did your bachelors and masters from ISI?

PC: Yeah.

MB: After completing your undergraduate studies, you went on to pursue a Ph.D. at UC Berkeley. Could you share how your time at Berkeley influenced the direction of your academic journey? Specifically, how did your experience there shape your research interests in statistics, and how did the environment at Berkeley contribute to the development of your ideas and academic goals?

PC: When I was completing my postgraduate studies, it was quite common at that time for students to apply for Ph.D. programs both in India and abroad, while also considering job opportunities in India. I applied to a few Ph.D. programs both within India and internationally, and the University of California, Berkeley, was one of the places I applied to.

Shyama Narendranath is a scientist at U R Rao Satellite Centre, ISRO. She is a part of Chandrayaan-2 and other Indian planetary programs. She has been awarded the Zubin Kembhavi award by the Astronomical Society of India.

Shyama Narendranath is a scientist at U R Rao Satellite Centre, ISRO. She is a part of Chandrayaan-2 and other Indian planetary programs. She has been awarded the Zubin Kembhavi award by the Astronomical Society of India.

The reason I chose UC Berkeley was because, at the time, they were doing significant work in areas like non-parametric statistics and robust statistics, which really caught my interest. I had been introduced to some of these topics during my postgraduate years, and they seemed like a fascinating direction to explore further. However, I’ll admit that, even then, I wasn’t entirely sure why I specifically wanted to go to Berkeley. It was more of a feeling that this was the right opportunity for me.

Once I arrived there, I was exposed to a lot of cutting edge research, particularly in function estimation and non-parametric statistics, which were among the most exciting areas of statistical research in those days. These areas had applications across various fields like chemistry, biology, and physics, and I quickly became involved in this vibrant research community.

Interestingly, at that time, getting a visa to travel to the U.S. was quite a challenge, which is not something students face today. In fact, there was a period when I even considered giving up on the idea of going to the U.S. and doing my Ph.D. in India instead. However, many of my professors and mentors advised me to take the opportunity for the exposure that studying abroad could offer. They encouraged me to consider the broader experience, not just the academic part, but the exposure to a different culture, society, and a broader set of ideas.

At Berkeley, the environment was so different from what I had experienced in India. While I was in a very academic focused institution, Berkeley had a much wider range of cultural and social activities that I could engage with. I remember being part of the film club, where I had the chance to watch a lot of films, something I didn’t have the same access to in India.

Berkeley was also politically active during those years, especially with movements against apartheid in South Africa. I vividly recall seeing protests and demonstrations outside the administrative building, where students were passionately advocating for change. These experiences, both academically and socially, had a profound influence on me, shaping not just my research interests but also my broader perspective on society and the world around me.

I spent three years at UC Berkeley, from 1985 to 1988, and those years were pivotal in both my academic and personal growth.

Fig 2. Prof. Chaudhuri did his Ph.D. in Statistics at University of California, Berkeley.

Fig 2. Prof. Chaudhuri did his Ph.D. in Statistics at University of California, Berkeley.

Swarnendu Saha(SS): And what was the political scenario in Bengal?

PC: Well, it was the left front government which was in power.

SS: You mentioned that the region you’re from has always been politically active, and there’s a certain sense of unrest that has persisted over time. I can imagine that growing up in such an environment, where political movements and activism are a constant presence, shaped your perspective.

When you went to UC Berkeley, the environment was, of course, very different. The culture, the people, even the physical space, everything would have felt new and unfamiliar. But at the same time, there were certain parallels, like the political activism on campus, the energy of the student movements, and the way people came together for causes they believed in.

Given that background, how did you make sense of these similarities and differences between your experience in India and what you saw at Berkeley? Was there a sense of connection between the political energy in both places, or did it feel like a stark contrast to what you were used to?

PC: The student community at Berkeley had a strong left-wing inclination, which reminded me of the political activism I’d witnessed in Bengal. However, there were key differences. The Berkeley student body was much more diverse, with students from a wide range of cultural backgrounds, which brought a unique blend of perspectives and ideas. This diversity fostered a sense of tolerance and adaptability, as we learned to coexist with people from different cultures.

Personally, I chose to stay in a student dorm during my first year at Berkeley, partly because I wasn’t familiar with the place and wanted a supportive environment. The dorm was an “international house”, and I ended up staying there throughout my time at Berkeley, as I enjoyed the community and the chance to interact with people from various countries and backgrounds.

SS: Were the dorms similar to the hostels that we have here?

PC: The hostels here are similar, but it is called the International House there because half of the residents were American and half were foreigners. It was always run on a sharing system. The prevalent practice was to keep two people in a room, and if it is two people in a room, it was the policy of the International house that one will be an American and one would be a non-American.

SS: So people could interact with other people from various cultures.

PC: Yes ! That was the case. See, at Berkeley, the dorms worked a bit differently. If you opted for a single room, it was more expensive. To keep costs manageable, I chose to stay in a shared room with a roommate who was often from a different country, not typically an American, since most American students lived off-campus. I remember having roommates from various countries, which exposed me to a wide range of cultures.

The international house where I lived had communal lunch and dinner tables, which created a unique environment for cultural exchange. We would often engage in political discussions over meals. At the time, there were significant events happening in the Middle East, and the political atmosphere was charged. Ronald Reagan was the president of the United States, and his administration was involved in several high-profile incidents. One of the most talked about events was the bombing of Libya, where Muammar Gaddafi was the leader. Another was the Iran-Contra affair, where leaked documents revealed illegal arms deals. Reagan’s approval dropped for a while, and he was almost viewed in the same light as Nixon. However, unlike Nixon, Reagan managed to survive politically, largely due to military officer Oliver North taking responsibility for the actions, which helped exonerate him.

In the evenings, we’d often gather in the lounge to watch the news on a large TV screen, discussing the latest developments. There were also weekly movie nights where we’d watch free films together. These experiences, especially dining and discussing politics with students from diverse backgrounds, gave me a broader perspective. I spent a lot of time with Palestinian students, and through conversations with them, I learned a great deal about the history of Palestine and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. It’s like you see the history in front of you. You know I mean they are having dinner with you. They are having lunch with you and you see and talk to these people.

SS: You have been a student as well as a teacher at ISI. You have spent a considerable amount of time here.

MB: Did you see Prof. Mahalanobis?

PC: No, he was not alive when I was a student.

SS: And how has ISI transformed in front of you?

PC: The field of statistics has evolved in many ways over the years. When we were students, our classes were small, with only 10 or 11 students, whereas now, class sizes have in-creased to 40 or 50 students. The curriculum has changed as well. Back then, the focus was primarily on mathematical statistics, and we had occasional assignments that involved computer work. But computing in those days was very different. We didn’t have personal computers or laptops. Instead, there was a mainframe system, and we used punch cards to input data. We would write out programs, hand them over to an operator who would type them into the system, and then the program would run on the computer. The next day, we’d get our output. Any errors would have to be corrected, and the cycle would continue. Students today likely can’t imagine working like that.

Now, of course, everyone has a computer or laptop in their office, and some even use tablets to perform computations. This has completely transformed the way we work. When I was at Berkeley, I encountered terminals for the first time and was introduced to email, although it was limited to internal communication within the U.S. At the time, communicating internationally wasn’t as easy as it is today, and things like printing were much more expensive. We had to get special permission to print our theses, and back then, the typesetting system called TEX (the precursor to LaTeX) was in use. I typed my thesis using TEX, which was quite the experience.

In terms of technology, I also saw the advent of workstations like the Sun workstation, which introduced the concept of multiple windows on a single screen. Before that, there was only one screen, and you couldn’t split it into multiple windows. The introduction of this new technology was a big shift in how we worked.

In terms of curriculum, statistics has evolved with the times. While our training focused more on theoretical and mathematical statistics, today’s courses incorporate a lot more data analysis. Students now spend significant time working with real data, using computers to run analyses, which wasn’t part of our training at the time.

Fig 3. Prof. Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis, Founded the Indian Statistical Institute (ISI) from a single laboratory at Presidency College.

Fig 3. Prof. Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis, Founded the Indian Statistical Institute (ISI) from a single laboratory at Presidency College.

SS: ISI started its journey right after the Independence, within a few years. And since then, we have also had the implementation of a good number of IITs; they have made a brand out of themselves. But even today, almost 20 years since the start of the IISERs, most people don’t know what the IISERs are. What is your take on this?

PC: The origins of ISI were quite different from its current form. As I mentioned in my lecture, ISI began in a small room at Presidency College, initially called the Statistical Laboratory. Prasanta Mahalanobis, its founder, was addressing statistical problems arising from various sectors, including government needs, in collaboration with others. As the work expanded, the need for trained statisticians grew, leading to the establishment of formal training programs.

In 1941, ISI introduced India’s first Master’s program in Statistics, initiated at University of Calcutta. This was the first formal academic program in statistics in the country, marking the beginning of structured education in the field. Over time, more programs were launched in different parts of the country.

It’s important to understand that ISI’s primary focus has always been on statistics, unlike the broader range of disciplines found in engineering or medical colleges. If we were to compare ISI to another institution, it might be more apt to compare it with medical colleges rather than IITs. While medical colleges produce doctors and IITs train engineers who contribute to society in specific ways, ISI produces statisticians who provide a different kind of service, more about supporting other fields rather than directly impacting daily life. Statisticians at ISI are educated in science, and the institution serves as a hub for science education, not as a traditional engineering or medical institution.

ISI’s contribution lies in creating high-quality scientific professionals. It offers an alternative path to those who wish to pursue science rather than engineering or medicine. While the latter fields are crucial for immediate societal needs, science provides long-term contributions that sustain technology and innovation. This is why science education is important, as it creates the foundation for future advancements. At ISI, you can also later diverge into technology, as many former students have done.

SS: What do you make of the National Education Policy (NEP)?

PC: Regarding the changes proposed in the National Education Policy (NEP), these decisions are often driven by administrative considerations rather than purely academic reasons. For example, the shift from a four-year to a three-year undergraduate program was made in 1978 to align with other science programs. NEP’s proposed changes, such as introducing four-year undergraduate programs, may have both positive and negative consequences. However, the real challenge lies in the implementation and the transition from the old system. Without proper planning, such transitions could lead to issues. The NEP doesn’t provide specific guidance on how it will affect the teaching process or curriculum at the grass-roots level, and that is where the concern lies.

SS: How do you see the differences between the students at ISI and those in other institutes?

PC: The key difference lies in the quality of students that ISI attracts, which is largely due to its brand name and reputation. ISI draws highly motivated students who are deeply interested in statistics, and this naturally leads to a more advanced level of coursework. This higher level of entry ensures that the courses are pitched at a more advanced level, leading to a certain inequality between top institutions like ISI and other universities. While this inequality helps in maintaining high standards, it can sometimes widen the gap between different types of institutions.

SS: What’s your take on the idea of celebrity status for scientists, similar to that enjoyed by people in the world of technology like Sundar Pichai or Bill Gates?

PC: I believe science should be pursued out of passion, not for fame. A scientist’s goal is to understand the natural world and contribute to the betterment of society through that knowledge. The pursuit of answers to unknown questions should be the primary motivation. While there are famous scientists whose work we learn from, they should not be seen as celebrities. The work itself is more important than the recognition or status that comes with it. Science is about curiosity and exploration, not about satisfying others’ expectations or seeking external validation.

The general public may not understand the nuances of a scientific career, especially in a society where engineering and medicine are seen as more immediately rewarding. But for those who choose science, the reward lies in the pursuit of knowledge, not in material gains or recognition.

MB: Could you share some insights on what you’re currently working on? Do you have any advice for young students who are considering a career in statistics?

Fig 4. The statistical laboratory set up by Prof.Mahalanobis at Presidency College, in 1931 which later became the ISI that is today.

Fig 4. The statistical laboratory set up by Prof.Mahalanobis at Presidency College, in 1931 which later became the ISI that is today.

PC: Statistics is a versatile field used across virtually every discipline both social sciences and natural sciences. If you’re considering a career in statistics, I’d recommend getting solid training from a good program. Beyond that, it’s important to stay open-minded and read widely beyond just statistics. You need to understand the broader role of science in society, why science exists and how it impacts the world.

Take, for example, the COVID-19 pandemic. Many studies came out, some of which were later retracted due to faulty data analysis. This highlights the importance of being cautious with data and rigorous in analysis. Statistics is about making sense of data to draw conclusions, and that requires not just technical expertise but also curiosity and critical thinking.

To be successful in statistics, you must focus on finding meaningful solutions to real world problems, not just following trends or trying to satisfy external pressures. Ultimately, science, like any field, should be pursued out of passion. It’s about solving mysteries and contributing knowledge, regardless of the external rewards.

MB: Thank you very much, sir, for your valuable insights. It has been a pleasure for us to host you this afternoon.