Why We Follow Trends, Even When They’re Bad for Us

In a world where trends shape our decisions, we often find ourselves following them even when they’re harmful. Why do we conform? The answer lies in our brain chemistry, where dopamine creates a reward loop that makes trend- following irresistible. Our psychological need to belong, a trait from our evolutionary past, further drives us to fit in with the crowd. By understanding these biochemical and social influences, we can break free from harmful trends and make decisions that align with our values.

Have you ever wondered why it has become so hard to resist buying things in this age of online transactions? In a world driven by social media, trends emerge rapidly, often influencing our actions in ways we don’t fully understand. Whether it’s a viral challenge, a new fashion, or a lifestyle choice, the urge to join in can be overwhelming. But why do we follow trends, even when they’re bad for us? The answer lies in a combination of psychological and biochemical factors that drive our behaviour.

Our tendency to follow trends is rooted in an evolutionary need for social connection, which has always been essential for human survival. Psychologist Pamela B. Rutledge emphasises that this behaviour isn’t a flaw but a natural drive to belong to a group. This need for social connection, considered as crucial as food and shelter, has been crucial since early humans collaborated to survive. While following trends today may not be as vital as escaping predators, our brains remain attuned to social signals, compelling us to align with others.

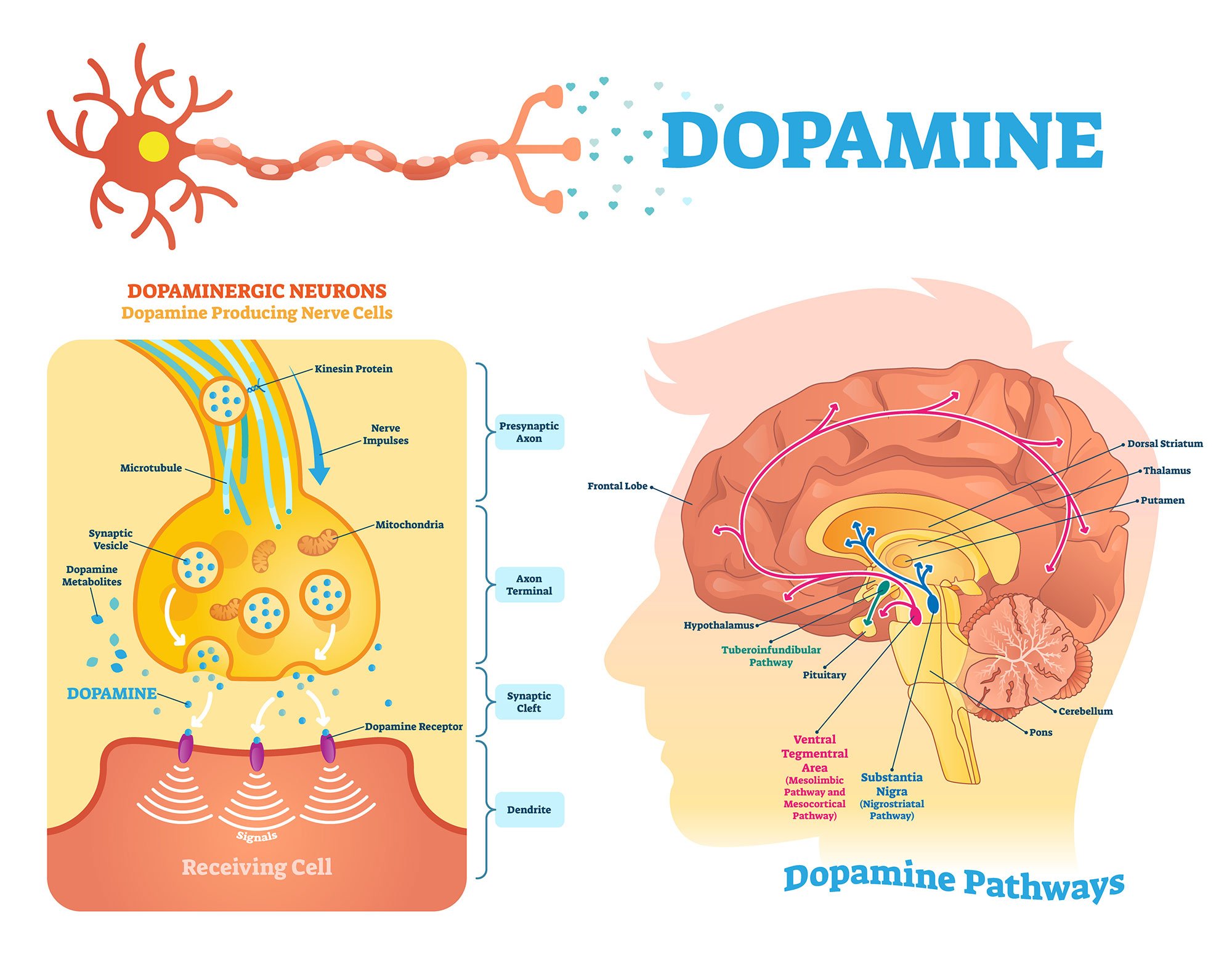

The Brain’s Chemistry: Dopamine and the Reward System

One of the key players in our tendency to follow trends is dopamine, a neurotransmitter in the brain. This chemical plays a crucial role in transmitting signals within the brain and other critical areas. Dopamine is associated with pleasure, reward, and motivation. When we participate in a popular trend, especially one that’s exciting or socially rewarding, our brain releases dopamine. This creates a sense of satisfaction and reinforces the behaviour, making us more likely to continue following the trend. The problem arises when this reinforcement happens regardless of the trend’s value or potential harm. The rush of dopamine can cloud one’s judgement, leading them to ignore risks in favour of immediate pleasure.

Fig 1. A survey conducted in the US among various age group and regions of residence have shown that most Americans overspend and overpay for leisure and luxury items when other cheaper items serve the same purpose. They also overspend in order to upgrade to the “latest and greatest” product. See [7]

Fig 1. A survey conducted in the US among various age group and regions of residence have shown that most Americans overspend and overpay for leisure and luxury items when other cheaper items serve the same purpose. They also overspend in order to upgrade to the “latest and greatest” product. See [7]

The Psychological Need to Belong

Our desire to fit in with others is another powerful force behind trend-following. Humans are inherently social beings, and our survival historically depended on being part of a group. This evolutionary trait still influences us today, as we instinctively seek approval from our peers. When everyone around us is adopting a new trend, we feel a psychological pull to do the same, fearing exclusion or judgement if we don’t. This need for belonging can be so strong that it overrides our logical thinking, pushing us to engage in trends even when they conflict with our values or well-being.

This psychological phenomenon, where we look to others to determine what’s right or acceptable, is termed social proof. If many people do something, we assume it must be the correct choice. This is amplified by cognitive biases like the bandwagon effect, where the popularity of an idea or behaviour makes it seem more credible. As a trend gains momentum, more people join in, creating a feedback loop that’s hard to resist. Confirmation bias further compounds this by leading us to seek out information that supports our decision to follow the trend, ignoring evidence that it might be harmful.

Our brains are wired to prefer familiar, easy-to-process information—a concept known as cognitive ease. Trends often become familiar quickly through repetition and widespread adoption, making them feel safe and desirable. This ease of processing reduces the mental effort required to evaluate the trend critically, leading us to follow it without questioning its merits or consequences.

Another factor that drives trend-following is the illusion of control. People often believe they can engage in a trend without suffering negative consequences, thinking they’re different or smarter than others who have been harmed. This sense of invulnerability, combined with the excitement of trying something new, can lead to risky behaviour, all in the name of keeping up with what’s popular.

Fig 2. Dopamine is transferred between neurons in the brain through a process called synaptic transmission, where dopamine molecules are released from the presynaptic neuron into the synaptic gap and bind to dopamine receptors on the postsynaptic neuron, thereby transmitting signals between neurons. See [5].

Fig 2. Dopamine is transferred between neurons in the brain through a process called synaptic transmission, where dopamine molecules are released from the presynaptic neuron into the synaptic gap and bind to dopamine receptors on the postsynaptic neuron, thereby transmitting signals between neurons. See [5].

Everyone is Susceptible

Rutledge says that everyone must follow trends, observe fads, and show their membership in social groups, without exception. However, Rutledge states that tweens, teenagers, and young adults are especially likely to embrace trends, including risky ones.

As children begin their journey towards independence as adults, they seek out ways to show their individuality. Ironically, this leads to desperate efforts to demonstrate belonging to socially accepted groups - and can fuel the urge to distinguish oneself through popular trends.

Rutledge suggests that you need to find a way to navigate through life successfully - “To achieve that, you must identify your true self”. She goes on to explain that because we are social beings, our development occurs within a social setting, and as we become more attuned to social cues, our interest in following (or disregarding) trends also increases. Popularity doesn’t hold much significance, even though it may seem important. However, from a biological standpoint, it is important for finding a partner.

Fig 3. Social proof suggests that our actions are shaped by observing those around us; we often seek validation from others to confirm our decisions. For example, a line outside a restaurant or a celebrity endorsing a brand of coffee can imply a sense of quality or desirability. Similarly, in the bio- pharmaceutical field, acknowledgment by peers or influential figures can be pivotal, potentially determining whether a new drug, vaccine, or technology secures investment. See [6].

Fig 3. Social proof suggests that our actions are shaped by observing those around us; we often seek validation from others to confirm our decisions. For example, a line outside a restaurant or a celebrity endorsing a brand of coffee can imply a sense of quality or desirability. Similarly, in the bio- pharmaceutical field, acknowledgment by peers or influential figures can be pivotal, potentially determining whether a new drug, vaccine, or technology secures investment. See [6].

Thus, the adolescent brain experiences quick growth in the crucial regions for social cognition. Research shows that adolescents reach their peak in facial recognition and reading abilities, leading to heightened awareness of their peers. At the same time, the prefrontal cortex, which is linked to reasoning and making choices, is the final part of the brain to mature completely (see fig 2), which explains why teenagers may resort to consuming Tide pods or snorting cinnamon to show off to their peers.

In the same way, Rutledge states that older individuals usually feel more confident in who they are, which can shield them from being easily influenced by current trends. Research indicates that social attention levels differ among age groups, as older individuals tend to pay less attention to social cues compared to younger individuals.

Understanding and Resisting Harmful Trends

Avoiding trends, though challenging, requires a nuanced understanding of how our biology, psychology, and evolutionary history shape our behaviour. Biochemically, trends stimulate dopamine release, the brain’s reward signal, making conformity feel gratifying. Physiologically, this dopamine-driven reward loop reinforces the behaviour, locking us into cycles of trend-following. Psychologically, we are programmed to seek social approval—a legacy of our evolutionary need for belonging. Behavioural biology further shows that our ancestors survived by adhering to group norms, a trait still embedded in us. However, by cultivating self-awareness and critical thinking, we can consciously override these deep-seated impulses.

Recognizing the biochemical and psychological factors that drive us to follow trends is the first step toward making better decisions. By understanding how all of these factors influence our behaviour, we can start to question trends more critically. Asking ourselves why we want to join a trend and considering its long-term impact can help us resist the pull of harmful behaviours and make choices that align with our true values. By seeking fulfilment in personal values rather than societal approval, we reduce our dependence on external validation. This helps foster individuality in a world that often prizes conformity.

In conclusion, while trends can be fun and socially rewarding, it’s important to approach them with a critical mind. By being aware of the psychological and biochemical forces at play, we can make more informed decisions and avoid blindly following trends that may not be in our best interest.

References

- Erin Blakemore, "Why do we blindly follow trends—even when they’re bad for us?" National Geographic, (2024).

- Badcock, P., "Explaining how the mind works A new theory," Research OUTREACH (110) (2019)

- Shruti Mandal, "Highlights on Asymmetric Human Brain", The Qrius Rhino (2021)

- Xiang Li et al., "Human torque is not present in the chimpanzee's brain", NeuroImage, 165, 285–293 (2018)

- Olivia Guy-Evans, "Dopamine Function in the Brain", Simply Psychology (2024)

- Masha Sibinovic and Eyram Adjogatse, "Demonstrating social proof", Probacure (2022)

- Motley, "Study: The Most Wasteful Spending Habits Among Americans," The Motley Fool, Mar. 22, 2019