Adaptation of Living Cells to Mechanical Forces

Mechanical forces play a crucial role in regulating cellular processes like growth, migration, and tissue repair. Cells actively sense their mechanical environment by forming dynamic adhesion sites called focal adhesions at the cell-matrix interface. These specialized structures act as mechanosensors, converting physical cues into biochemical signals that guide cellular behavior. This article explores how focal adhesions enable cells to probe their surroundings and respond to mechanical stimuli.

Cells are the building blocks of life, carrying out essential functions to keep organisms alive. To function properly, cells must constantly sense and respond to their environment. While biochemical signals like hormones and nutrients are well known for influencing cell behavior, mechanical forces also play a crucial role in regulating how cells grow, move, and function [1]. Cells experience various types of mechanical forces, including tension, compression, and shear stress. These forces come from their surroundings, such as the stiffness of the tissues they reside in or the physical pressure exerted by neighboring cells. Mechanical signals help shape tissues during development, guide wound healing, and even influence diseases like cancer and fibrosis. For example, changes in tissue stiffness can control how stem cells develop into different types of cells, determining whether they become bone, muscle, or fat [2]. Similarly, abnormal mechanical forces can drive cancer progression by altering cell signaling and promoting uncontrolled growth [3].

Understanding how cells respond to mechanical forces is critical for many fields, including regenerative medicine, bioengineering, and cancer research. By studying the mechanical aspects of cell behavior, scientists can design better biomaterials, develop new therapeutic approaches, and improve medical treatments. Integrating mechanics into cell biology provides a more complete picture of how cells function and adapt to their environment, leading to advancements in both basic research and clinical applications.

How Do Cells Sense Mechanical Signals?

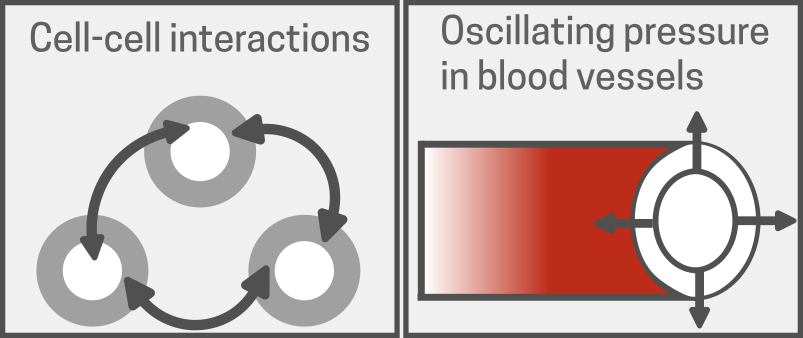

Cells are constantly sensing and interacting with their environment. They respond to a variety of external signals by adjusting their internal processes. One key way cells communicate with their surroundings is through specialized structures called focal adhesions (FAs). These adhesion sites connect the cell to the extracellular matrix (ECM), allowing mechanical and biochemical signals to be transmitted. Focal adhesions are protein structures that connect cells to the extracellular matrix. Cytoskeleton, the cell’s internal framework, is a structural network composed of actin filaments, microtubules, and intermediate filaments, which help maintain the cell’s shape and stability. Among these, actin stress fibers are particularly important for generating mechanical forces. These fibers interact with myosin motor proteins, which use chemical energy to produce contractile forces by causing actin filaments to slide past one another.

Focal adhesions play a crucial role in transmitting these contractile forces to the ECM, acting as mechanosensors. This allows cells to physically pull on the matrix and assess its stiffness, as well as detect external mechanical cues. In response, cells adjust their behavior by modifying internal signaling pathways, ultimately influencing functions such as migration, differentiation, and growth. By probing the rigidity of the ECM, cells can determine whether their environment is suitable for movement, division, or structural changes. This process is essential for many biological functions, including tissue development, wound healing, and disease progression.

How Do Focal Adhesions React to External Mechanical Forces? Focal adhesions (FAs) are complex, multi-protein structures that connect the cell’s cytoskeleton to the extracellular matrix (ECM), allowing cells to sense and respond to mechanical forces. Unlike physical adhesion, which is a passive process, biological focal adhesions are highly dynamic. Cells actively remodel and reorganize their focal adhesions in response to external mechanical cues. This ability to adapt is crucial for cellular processes such as migration, differentiation, and survival [8].

Fig 1. Cells experience different physical forces in their environment, which affect how they behave and function. As an example, this two figures show two types of forces — forces from nearby cells and changing pressure inside blood vessels. These forces help guide cell movement, attachment, and overall response. Adapted from [17].

Fig 1. Cells experience different physical forces in their environment, which affect how they behave and function. As an example, this two figures show two types of forces — forces from nearby cells and changing pressure inside blood vessels. These forces help guide cell movement, attachment, and overall response. Adapted from [17].

Focal Adhesion Adaptation to Mechanical Forces

Cells are exposed to various mechanical forces, including stretching, compression, and shear stress. To maintain stability and function, focal adhesions must adjust their size, composition, and activity in response to these forces. Research shows that FAs grow, stabilize, or disassemble depending on the mechanical environment. For instance, when subjected to sustained mechanical forces, FAs enlarge and become more stable, reinforcing the connection between the ECM and the cytoskeleton [4].

Focal adhesions are especially sensitive to time-dependent forces. Their orientation and dynamics change in response to cyclic stretching, which is critical for cells in mechanically active tissues like the heart. Studies indicate that under slow, static, or quasi-static stretch, FAs align along the stretch direction. However, under fast cyclic stretch, they reorient perpendicularly to the applied force [5]. This behavior helps cells maintain structural integrity in tissues experiencing rhythmic mechanical forces, such as the cardiac and lung tissues.

Molecular Composition and Force Sensitivity

Focal adhesions are composed of multiple proteins, including integrins, talin, vinculin, and paxillin, which link the ECM to the actin cytoskeleton. These proteins work together to translate mechanical forces into biochemical signals—a process known as mechanotransduction [10]. Experimental studies have demonstrated that FA components are highly force-sensitive, and their assembly and disassembly are influenced by ECM rigidity and external mechanical forces [9].

When force is applied to FA-associated proteins, it can alter the energy landscape of molecular interactions, effectively switching binding states on or off. This process regulates FA stability, influencing cell migration and adhesion strength. For example, when the ECM is stiff, focal adhesions become larger and more stable, reinforcing the cell’s attachment to its environment. Conversely, on soft matrices, FAs remain small and transient, allowing greater cellular movement [2].

The Role of Catch Bonds in Force-Dependent Adhesion

One of the most intriguing aspects of focal adhesion mechanics is the presence of catch bonds—molecular interactions that become stronger under moderate force but weaken at very high forces. Recent studies have shown that focal adhesions grow in the direction of tensile force, and their stability increases up to a certain force threshold before decreasing [6].

Catch bonds can be intuitively understood by imagining two interlocked hooks. If the hooks are loosely connected, they can easily detach. However, when a pulling force is applied, the hooks interlock more tightly, making them harder to separate. Similarly, mechanical forces induce conformational changes in FA proteins, strengthening their binding interactions. This force-dependent stabilization allows cells to maintain robust adhesion under physiological conditions while still being able to detach when necessary for processes like migration [10].

Fig 2. An illustration showing a cell attached to the extracellular matrix (ECM) through two focal adhesions (FAs). A zoomed-in inset (dotted box) highlights the FAs as a collection of ligand-receptor molecular bonds, demonstrating how the cell anchors itself to the ECM. Adapted from [17].

Fig 2. An illustration showing a cell attached to the extracellular matrix (ECM) through two focal adhesions (FAs). A zoomed-in inset (dotted box) highlights the FAs as a collection of ligand-receptor molecular bonds, demonstrating how the cell anchors itself to the ECM. Adapted from [17].

A theoretical model of Focal adhesion

There is a straightforward theoretical model to explain how focal adhesions (FA) grow, remain stable, and align themselves under both constant (static) and changing (cyclic) stretches. The model combines a novel approach of understanding how stretch influences the formation and breakage of molecular bonds with the elasticity of the cell-substrate system.

Focal adhesions are often modeled as clusters of ligand-receptor bonds, behaving like Hookean elastic springs. Bell’s pioneering work applied kinetic theory to describe the stability of these adhesion clusters [11]. In this model, receptors (R) on the cell surface interact with extracellular matrix (ECM) ligands (L) to form ligand-receptor complexes (RL). The chemical kinetics is described as:

where \(K_\text{on}\) and \(K_\text{off}\) denote the total association and total dissociation rate of ligand-receptor bonds.

In Bell’s model, slip bonds exhibit an exponential increase in dissociation rate with applied mechanical force, meaning they become weaker as force is applied. This behavior is described by:

where \(k_0\) is the natural dissociation rate without force, \(f_b\) is the applied bond force, and \(f_0\) is a characteristic force scale (typically in the piconewton range for focal adhesions).

On the other hand, the dissociation rate for catch bonds which get strengthened under force has been proposed as [12, 13]

where \(k_\text{slip}\) and \(k_\text{catch}\) denote the rate constants for dissociation of the ligand-receptor pair via a slip pathway promoted by the force and a catch pathway opposed by the force respectively.

The dynamics of FAs are subjected to fluctuations in the surrounding micro-environment. Thus, bonds can also undergo stochastic breaking or rebinding. To study the time evolution of the FA cluster, a master equation has been written by coupling the elasticity of the cell-matrix system with the statistical behavior of bond association and dissociation processes

where \(P_n(t)\) is the probability that \(n\) bonds are formed at time \(t\). The first two terms on the right-hand side represent the gain term, i.e., the tendency for the number of bonds in state n to increase due to the formation of new bonds in state (n − 1) and the dissociation of bonds in state (n + 1), respectively. The last term represents the loss of bonds in state n, whereas \(K_\text{on}\) and \(K_\text{off}\) denote the total association and total dissociation rate of bonds at the respective state, n, at any instant of time t.

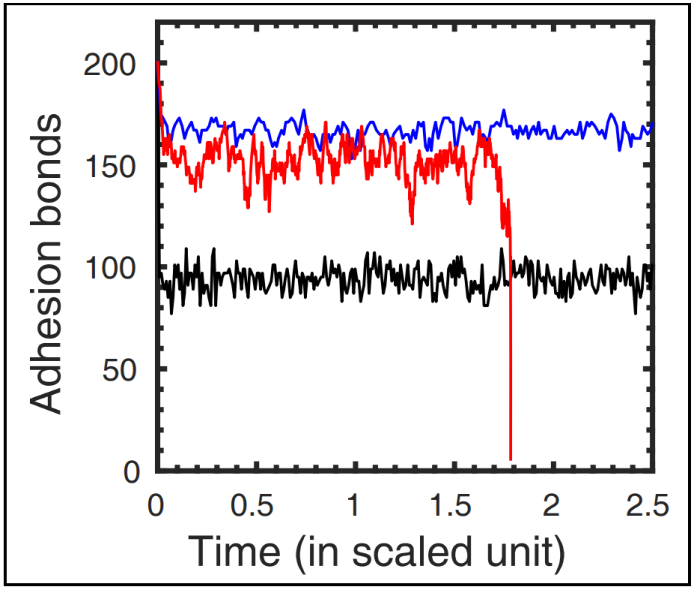

Master equation is often solved numerically using the Monte Carlo method. One of the most widely used approaches for this is Gillespie’s algorithm [14,15], which efficiently simulates the stochastic dynamics of chemical and biological systems. This method is particularly useful for studying the time-dependent behavior of bond clusters, capturing their formation and dissociation events under fluctuating conditions. By generating statistically accurate trajectories, Gillespie’s algorithm provides critical insights into the evolution of bond populations and their response to external forces.

Fig 3. Time evolution of the number of closed bonds in an adhesion cluster under applied force. Stochastic trajectories are generated by simulating the Master equation using representative force values and corresponding reaction rates. Black and blue trajectories indicate stable adhesion clusters, while the red trajectory represents an unstable cluster where all bonds eventually dissociate. Adapted from [17].

Fig 3. Time evolution of the number of closed bonds in an adhesion cluster under applied force. Stochastic trajectories are generated by simulating the Master equation using representative force values and corresponding reaction rates. Black and blue trajectories indicate stable adhesion clusters, while the red trajectory represents an unstable cluster where all bonds eventually dissociate. Adapted from [17].

Why this study is important

Cell mechanosensing is essential for detecting and responding to mechanical stimuli in the environment, enabling cells to regulate critical functions such as migration, adhesion, differentiation, and proliferation. This process is vital in tissue development, wound healing, and immune responses, where cells must adapt to varying mechanical forces. Mechanosensing allows cells to interpret physical cues from the extracellular matrix and neighboring cells, influencing gene expression and signaling pathways. Dysregulation of mechanosensing can lead to diseases such as cancer and fibrosis. Understanding how cells sense and respond to forces provides insights into tissue engineering, regenerative medicine, and targeted therapeutic strategies.

References

- Discher, D. E., Janmey, P., & Wang, Y. (2005). Tissue cells feel and respond to the stiffness of their substrate. Science, 310(5751), 1139-1143.

- Engler, A. J., Sen, S., Sweeney, H. L., & Discher, D. E. (2006). Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell, 126(4), 677-689.

- Butcher, D. T., Alliston, T., & Weaver, V. M. (2009). A tense situation: forcing tumour progression. Nature Reviews Cancer, 9(2), 108-122.

- Balaban, N. Q., Schwarz, U. S., Riveline, D., Goichberg, P., Tzur, G., Sabanay, I., ... & Geiger, B. (2001). Force and focal adhesion assembly: a close relationship studied using elastic micropatterned substrates. Nature Cell Biology, 3(5), 466-472.

- Cui, Y., Hameed, F. M., Yang, B., Lee, K., Pan, C. Q., Park, S., & Sheetz, M. (2015). Cyclic stretching of soft substrates induces spreading and growth. Nature Communications, 6, 6333.

- Elosegui-Artola, A., Oria, R., Chen, Y., Kosmalska, A., Pérez-González, C., Castro, N., ... & Roca-Cusachs, P. (2016). Mechanical regulation of a molecular clutch defines force transmission and transduction in response to matrix rigidity. Nature Cell Biology, 18(5), 540-548.

- Geiger, B., Spatz, J. P., & Bershadsky, A. D. (2009). Environmental sensing through focal adhesions. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 10(1), 21-33.

- Parsons, J. T., Horwitz, A. R., & Schwartz, M. A. (2010). Cell adhesion: integrating cytoskeletal dynamics and cellular tension. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 11(9), 633-643.

- Sun, Z., Guo, S. S., & Fässler, R. (2016). Integrin-mediated mechanotransduction. Journal of Cell Biology, 215(4), 445-456.

- Thomas, W. E., Vogel, V., & Sokurenko, E. (2008). Biophysics of catch bonds. Annual Review of Biophysics, 37, 399-416.

- G I Bell, Models for the Specific Adhesion of Cells to Cells, Science, Vol.200, pp.618–627, 1978.

- R De, A General Model of Focal Adhesion Orientation Dynamics in Response to Static and Cyclic Stretch, Communications Biology, Vol.1, Article No. 81, 2018.

- Y Pereverzev, O V Prezhdo, M Forero, E Sokurenko and W Thomas, The Two-pathway Model for the Catch-slip Transition in Biological Adhesion, Biophys. J., Vol.89, pp.1446–1454, 2005.

- Gillespie, D. T. (1976). A General Method for Numerically Simulating the Stochastic Time Evolution of Coupled Chemical Reactions. Journal of Computational Physics, 22(4), 403-434.

- Gillespie, D. T. (1977). Exact Stochastic Simulation of Coupled Chemical Reactions. The Journal of Physical Chemistry, 81(25), 2340-2361.

- De, R. A general model of focal adhesion orientation dynamics in response to static and cyclic stretch. Commun Biol 1, 81 (2018).

- De, R. Cell Mechanosensing. Reson 24, 289–296 (2019).