Melding Data with Science: A Perspective on the Recent Nobel Prizes

The advent of artificial intelligence (AI) is altering paradigms faster than ever. In hindsight, the 2024 Nobel Prizes in Physics and Chemistry were a recognition of this remarkable phase of human endeavour. This essay attempts to acquaint the general reader to underpinning developments that has led to such a surge. Creative harnesses that facilitated the Nobel recognitions are invoked, along with emergent opportunities and subtle caveats.

Prior to his death, Alfred Nobel, the Swedish scientist, inventor, and entrepreneur, instituted his namesake awards for those who “shall have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind.” Worldwide, the Nobel prizes count amongst the highest achievable recognitions; they elevate individuals for life and bring immense prestige to associated institutions (1). Historically, the Prizes in the natural sciences have been associated with ‘fundamental discoveries’ in sub-disciplines within Physics, Chemistry, and Physiology (or Medicine), typically arriving decades after the initial revelation. Speculative conjectures about the nature of the prizes run rife until their announcements in October each year.

By standard measure, the 2024 Nobel Prizes to John Hopfield and Geoffrey Hinton in Physics (“for foundational discoveries and inventions that enable machine learning with artificial neural networks”) to David Baker (“for computational protein design”), and to Demis Hassabis and John Jumper in Chemistry (“for protein structure prediction”), are unconventional. Not only do the citations defy disciplinary expectations, but part of the Chemistry award is for research reported about half a decade ago (2). Strikingly, John Jumper (born 1985) is the youngest Chemistry laureate in the last seven decades. Collectively, the prizes are an unequivocal nod to artificial intelligence (AI), a product of the human mind arguably poised to overtake human creativity (3).

This essay attempts to thread the inception and evolution of AI and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) in the context of the two 2024 Prizes and their culmination to sine qua non in science and life. While the writing does not engage in pedagogy, the references should adequately orient the reader for deeper appreciation.

Inception

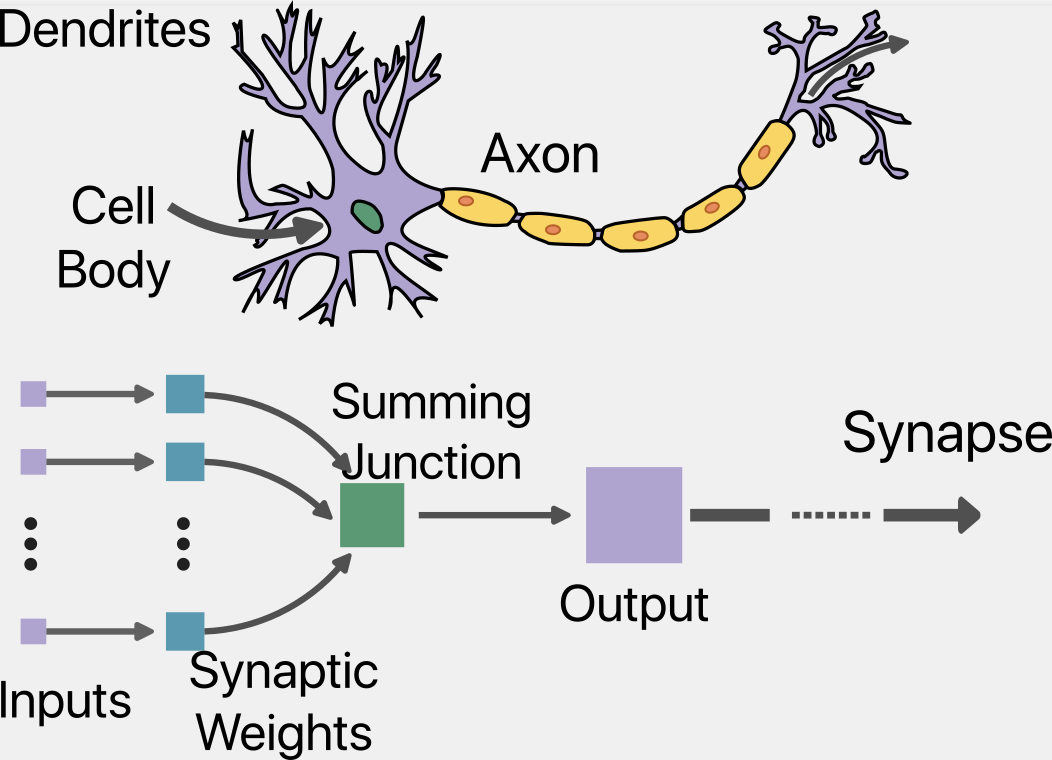

Artificial Intelligence (AI) represents a growing spectrum of data-based algorithmic technologies that aim to replicate decision-making and other nuances of the human mind. Mathematical recapitulation of the brain’s “nervous activity” is originally attributed to the fortuitous crossing of paths between a neuropsychologist, Warren McCulloch, and a self-taught logician, Walter Pitts. As early as 1943, McCulloch and Pitts suggested that the brain’s neural events manifest as calculable logic (4). Their analogy, schematically described in Fig 1, between synaptic activity and logic gates led to the concept of “neural nets” and marked the epoch of artificial neural networks (ANN). Close on the heels of McCulloch-Pitts, in 1949, psychologist Donald Hebb published “The Organization of Behaviour.” Hebb’s prescient text related the influence of the environment on behaviour and related synaptic organization to network dynamics (5, 6). Hebb evinced that learning and memories relate to the co-activation of multiple neurons.

Fig 1. Schematic depiction of McCulloch-Pitts Model, (adapted from (47)). The inputs (violet) bring in signals from neighbouring neurons, acting as the dendrites. The summing function mimics the cell body by generating impulses that are passed along the axon. The connection from the output to other artificial neurons represents the axon.

Fig 1. Schematic depiction of McCulloch-Pitts Model, (adapted from (47)). The inputs (violet) bring in signals from neighbouring neurons, acting as the dendrites. The summing function mimics the cell body by generating impulses that are passed along the axon. The connection from the output to other artificial neurons represents the axon.

The combined insights of McCulloch, Pitts, and Hebb were foundational to the development of AI. However, the next three decades observed ebbs and rises due to disinterested funding agencies. Luckily, more exciting developments in computational hardware helped sustain interest in ANNs. Notable work from this era includes Frank Rosenblatt’s implementable feedforward network for image interpretation (7). His introduction of the “perceptron” was a direct attempt to mimic the brain’s neural structures. While attractive in its simplicity, the original perceptron died a natural death owing to limitations enunciated by Marvin Minsky and Seymour Papert (8). The intermingling of various disciplines during these early endeavours is evident from the article curiously titled “What the Frog’s Eye Tells the Frog’s Brain,” published in 1959 in the Proceedings of the Institute of Radio Engineers (9).

The Hopfield Network and the Boltzmann Machine

John Hopfield began his career in solid-state physics. A science maverick, he meandered from physics to biochemistry and spectroscopy prior to attempts at replicating the brain’s workings. It is interesting that at the time of the 2024 Prize, he was (and still is) the Howard A. Prior Professor of Molecular Biology (Emeritus) at Princeton University. It is unsurprising to attribute the remark, “I didn’t really think of this as moving into biology, but rather as exploring another venue in which to do physics,” to this polymath (10).

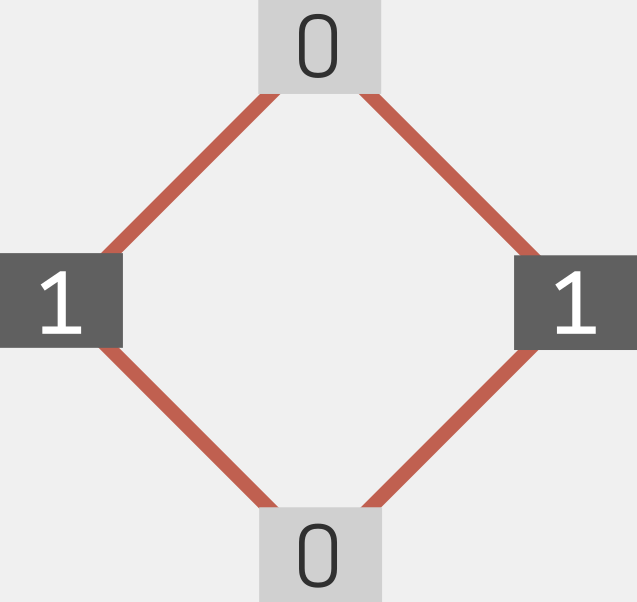

Hopfield was inspired by collective phenomena in physics commonly studied by the lattice-based Ising model. Noting that an array of magnetic spins respond collectively when exposed to a perturbation (such as a magnetic field), Hopfield reasoned that interconnected neurons would elicit similar responses when subjected to an impulse (such as an image or sound). The basic Hopfield network was thus born (11). The model assigned input layers (akin to dendrites), weights (akin to synapses), and nodes (akin to the neuronal centre) to an elementary ANN. The nodes were assigned a binary number (0 or 1), and their energy was deduced from a linear combination of the weights and values of other interconnected nodes; see Fig 2. The result was a dynamical recurrent network for associative memory. Hopfield then advanced his model for graded response incorporating continuous-time dynamics (12). Over the next few years, Hopfield consolidated and refined his model in association with other neuroscientists such as David Tank.

Fig 2. A Hopfield network consists of a single layer of neurons (represented by black and gray nodes), with connectivities (red lines). The neurons adopt only two values. Adapted from (48).

Fig 2. A Hopfield network consists of a single layer of neurons (represented by black and gray nodes), with connectivities (red lines). The neurons adopt only two values. Adapted from (48).

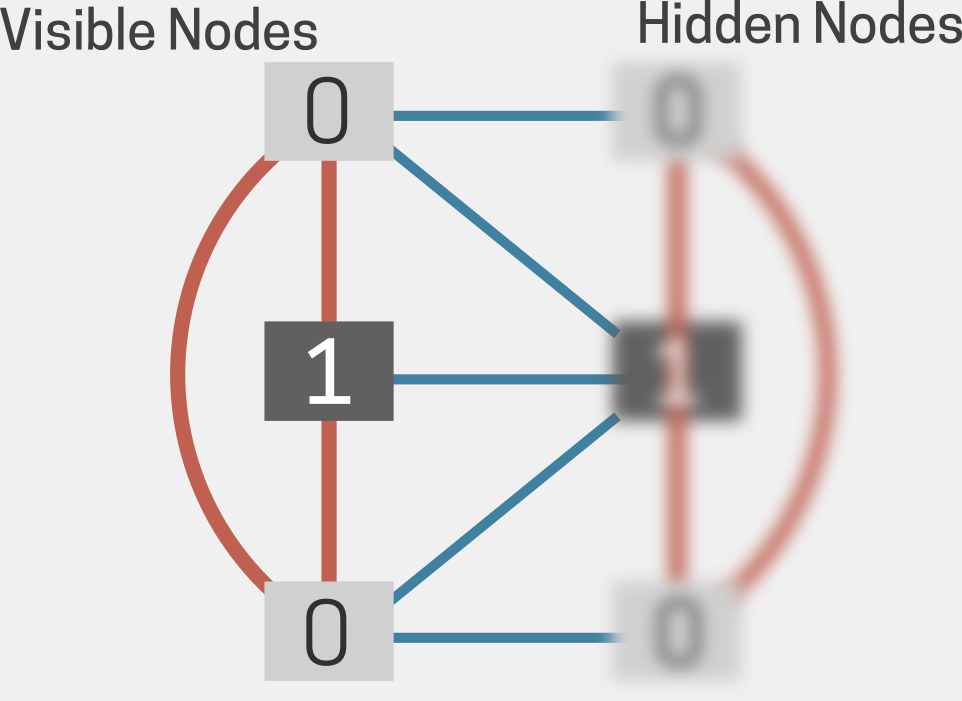

The early Hopfield model settled into energy valleys (or minima); this was partially addressed by the introduction of a fictive ‘temperature,’ T. Leveraging the idea of thermal stochasticity, another physicist, Geoffrey Hinton, introduced the concept of the Boltzmann machine (Fig 3), replacing Hopfield’s binary nodes with weights (13). Along with local biases, the modified network now represented statistical distributions of patterns, with an energy E and T-dependent Boltzmann-like probabilities of states. Large numbers of hidden units in the Boltzmann machine learned complex associations. Remarkably, this development marked neural network shifts to generative models capable of generating new data based on the training patterns. Hinton developed the idea of backpropagation, whereby hidden units not connected to the input or output help refine the network (14).

Deeper and Denser

The original breakthroughs saw successful applications in image recognition, language modelling, and clinical data. Important work in this era by LeCun, Benjio, and Fukushima (15, 16, 17) led to the development of deep convolutional networks. However, training efficient yet deep multilayered networks remained a recurring challenge. The next breakthrough, vis-a-vis Hinton again, arrived in the form of the Restricted Boltzmann Machine (RBM). The RBM (Fig 4) eliminated connectivities (weights) between nodes in the same layer and led to the emergence of the much faster contrastive divergence method (18). This marked the advent of deep neural networks with dense interconnectivity between millions of neurons that continue to develop for performing previously unimaginable tasks (19).

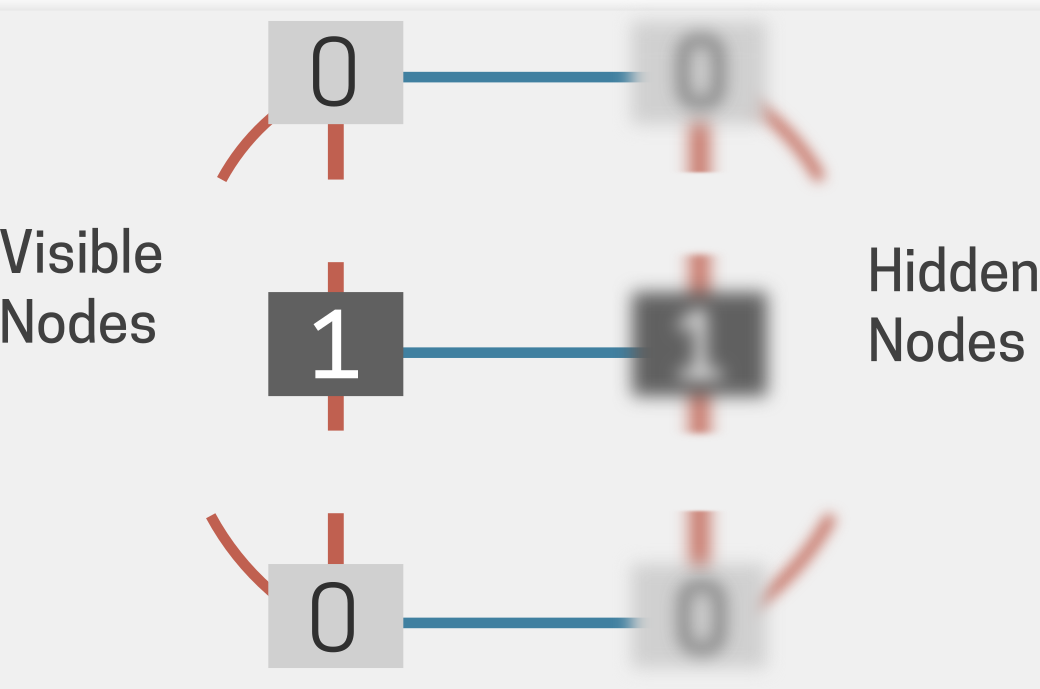

Fig 3. Schematic of a Boltzmann machine as a grid of interconnected nodes, with the clear nodes representing visible nodes and the blurred ones representing hidden nodes. The visible nodes are linked to the hidden nodes (illustrated by additional blue lines between the layers), indicating their influence on the network’s function. Adapted from (48).

Fig 3. Schematic of a Boltzmann machine as a grid of interconnected nodes, with the clear nodes representing visible nodes and the blurred ones representing hidden nodes. The visible nodes are linked to the hidden nodes (illustrated by additional blue lines between the layers), indicating their influence on the network’s function. Adapted from (48).

Today, AI methods with underlying DNNs are indispensable in large segments of human endeavour. Within the parent category of one of the 2024 prizes, AI has aided discoveries in plasma physics and biological physics (20). More easily recognizable applications today include image and voice recognition, language processing and translation, market recommendations, customer-relationship management, health data management, and human health and drug discovery (21). The last aspect bears upon the other focal point of this essay, namely the 2024 Prize in Chemistry.

Folding the Machineries of Life

Life is underwritten by molecules obeying physical laws. Some of these molecules are information templates, while others synchronize and execute the underwritten rules. Key participants in this complex machinery are proteins, chains of twenty naturally occurring units (amino acids) that perform myriad duties that range from facilitating chemical reactions to acting as scaffolds and signal transmitters to offering defences and preventing organismal damage. To carry out their mandate, the vast majority of these voracious workers must acquire very specific three-dimensional shapes or structures within a very short time. In the mid-twentieth century, Christian Anfinsen demonstrated, with a series of innovative experiments, how the acquisition of specific structures was a direct result of the sequence of the amino acids (22). Anfinsen was awarded the Chemistry Nobel Prize in 1972.

Over seven odd decades, the protein folding problem has intrigued, attracted, and flummoxed communities of science practitioners (23). Cyrus Levinthal’s thought experiment, ca. 1968, highlighted how, if random sampling of all possible conformations were allowed, the folding time would likely exceed the age of the universe. Levinthal’s paradox inspired crucial physical explanations (24) alongside vast experimental efforts (25). Yet, a solution to the protein folding problem remained elusive, limiting advancement not just in medicine and therapeutics but in fundamental progress as well.

Though aided in part by the advent of computational techniques, capturing the precisely folded protein state has predominantly been deemed an experimental prerogative. Traditionally, the gold standard was X-ray crystallography, which reported the relative positions (coordinates) of individual protein atoms. Additionally, complementary techniques such as nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and low-temperature cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) have offered crucial biological insight (26). Collectively, experimental advances underlie the rapid rise in the number of reported entries in the protein structural database (PDB), reaching 0.23 million entries in about three decades (27). It is worth noting that this milestone was achieved with tremendous investment in laboratory resources and human effort. It was realized that sole reliance on experimental methods would not break barriers or induce paradigm shifts in protein structural elucidation.

Fig 4. Schematic of a Restricted Boltzmann Machine is similar to a Boltzmann machine but lacks connections within the same layer. RBMs are foundational in deep learning, often used as building blocks for deep belief networks. Adapted from (48).

Fig 4. Schematic of a Restricted Boltzmann Machine is similar to a Boltzmann machine but lacks connections within the same layer. RBMs are foundational in deep learning, often used as building blocks for deep belief networks. Adapted from (48).

AlphaFold: Can we Replace the Lab?

Founded as a start-up in 2010, DeepMind aimed to transform the field of AI. Led by Demis Hassabis, it achieved early success in Deep Reinforced Learning. Taken over by the technology giant Google a few years later, DeepMind’s modules were defeating world champions in games such as Go, a Japanese game akin to Chess. Powered by other successes such as the AlphaStar and the Wavenet, DeepMind segued to protein structure prediction in 2020.

Freshly armed with a PhD in theoretical chemistry from the University of Chicago, John Jumper joined DeepMind in 2017. Prior to graduate school, Jumper had spent a few years at D.E. Shaw Research, a computational drug development company based in New York. At DeepMind, Hassabis and Jumper assembled a diversely trained team of mathematicians, physicists, chemists, and computer scientists. This team would go on to create an AI tool that could predict protein structure with only the amino acid sequence as input (29). At the Critical Assessment of Protein Structure (or CASP) biennial competition in 2018, this tool was able to best the next entry (from academia) by a long measure. Emboldened, the team then redesigned their neural network architecture to emerge with their now famous tool, AlphaFold. The new AI technology not only topped CASP in 2020 but yielded structures virtually identical to those reported via actual experiments. The algorithm, published in 2021 (30), unveiled the era of AI as a potential replacement for human effort in an actual wet lab (31). Later versions of AlphaFold have been empowered for the deduction of protein structures complexed with other molecules of biological significance (32), hugely impacting fields such as drug discovery and therapeutics. Despite some reasonable scepticism (see concluding section), AlphaFold’s value stands ratified not just by the Nobel recognition but also by a citation surge at nascency.

Large segments of the human proteome had awaited inspiration, resources, and experimental structural resolution. Soon after the publication of their algorithm, the AlphaFold team quickly moved to deduce a previously unimagined number (exceeding 200 million) of structures based on their known sequence. As of today, this technology has helped fill vast structural gaps within extant genomes, giving rise to an ‘AlphaFold database’ (33). Such a leap in structural information is emerging as an important crucible for protein-based therapeutic discovery (34, 35)

Extra-Genomic Design

Protein function is, in large part, enabled by the intricate details of structure. The backbone fold alignment and orientations of the sidechain cooperate to execute precise roles, such as priming molecules and ligands for chemical reactions. De novo protein design is, in some sense, the reverse of the folding problem - the function informs the fold, which in turn dictates the sequence. Importantly, this approach is not limited to sequences found in nature and does not demur from extra-genomic design.

The first artificial sequences were inspired by folds prevalent in natural proteins (36, 37). Early efforts culminated in the design of the first artificial protein, ‘Top7’, whose predicted structure was subsequently validated by experiment (38). The main architect, David Baker, owed this success to his own computational program, Rosetta, released a few years earlier in 1999 (39). While this program did not leverage any machine learning methods, it synchronized available structural data with physics-based methods. In the years following, Baker assembled large teams to progressively predict, design, and validate ranked structural folds capable of executing functions outside those dictated by nature. Unlike the AlphaFold team, the team includes scientists trained in experimental techniques. Today, Baker’s Institute for Protein Design iterates between targeting new functions to AI-based algorithm development to design proteins that are not the natural products of evolution (40). Emergent developments through this pipeline include anti-toxins (such as those against snake venom), synthetic receptors, protein-based nanomaterials, and customized vaccines. Baker is also credited with popularizing the protein folding problem via the crowdsourced online tool Foldit (41). Based on the original Rosetta, this publicly available computer game offers one the chance to leverage their ingenuity and create unique protein configuration structures with novel functions (42).

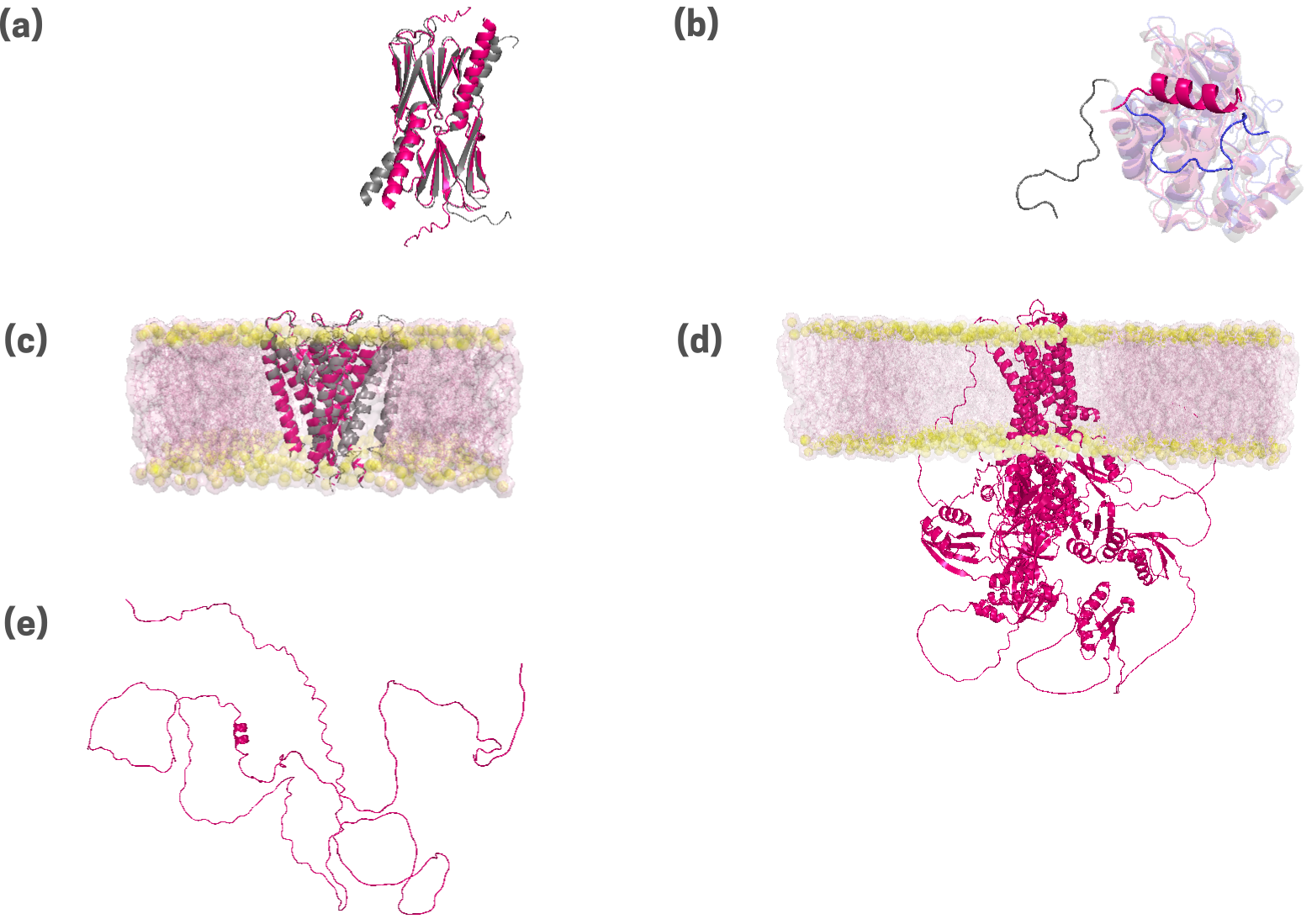

Fig 5. Protein structures predicted by the AlphaFold2 algorithm are presented for a diverse set of proteins. These include a chaperone, HSP14 (a); an enzyme, Abselson tyrosine kinase, or Abl (b); a transmembrane potassium channel, KcSA (c);a transmembrane copper transporter, ATP7B (d); and an intrinsically disordered protein, DISC1 (e). Experimental structures, where available in the protein data bank database, are superimposed in grey. Backbone root mean squared deviations (RMSD, in Å units) are provided. For the transporters, the surrounding cellular membrane bilayer is putatively modeled, and depicted in yellow (lipid headgroups) and pink (aliphatic tails). The inability of AlphaFold2 to predict alternate (polymorphic) structures is demonstrated by the omission of the segment corresponding to the inactive state of Abl (see b; in blue).

Fig 5. Protein structures predicted by the AlphaFold2 algorithm are presented for a diverse set of proteins. These include a chaperone, HSP14 (a); an enzyme, Abselson tyrosine kinase, or Abl (b); a transmembrane potassium channel, KcSA (c);a transmembrane copper transporter, ATP7B (d); and an intrinsically disordered protein, DISC1 (e). Experimental structures, where available in the protein data bank database, are superimposed in grey. Backbone root mean squared deviations (RMSD, in Å units) are provided. For the transporters, the surrounding cellular membrane bilayer is putatively modeled, and depicted in yellow (lipid headgroups) and pink (aliphatic tails). The inability of AlphaFold2 to predict alternate (polymorphic) structures is demonstrated by the omission of the segment corresponding to the inactive state of Abl (see b; in blue).

Into the Future

In the last decade, artificial intelligence-based technologies have permeated human lives at previously inconceivable levels. The average individual, rural or urban, is exposed to, and at the same time, unknowingly contributes to, ever-expanding data that inform further development. Everyday interfaces include search engines, voice assistants, social media, and guided choices in digital shopping. Somewhat less routinely, people may use AI-assisted genealogy services or rely on AI-assisted diagnostics for acute diseases. Generative AI methods, such as ChatGPT that replicate human responses have generated further excitement.

While the horizons expand, it may be prudent to tread with caution, at least for the time being. While AI aids both knowledge acquisition and application, it appears that the effects may culminate non-uniformly (43). Effects on early exposure and over-usage may modulate the natural receptivity and intelligence of young brains; potential evolutionary consequences may be indeterminable. Blurred lines between reality and artificially generated scenarios may affect finely balanced societal, political, and legal environments. For those in proteomic work, it is important to keep in mind the limitations of tools such as AlphaFold. While quick and efficient and undoubtedly a boon for structural biology and structure-based drug design, AlphaFold is primarily a prediction algorithm that does not inform about the physico-chemical drivers of protein folding (43, 44, 45). Emergent work describes the limitations of this tool for effectively predicting protein folds associated with chemical staples or those with high disorder (see Fig 5).

Despite purported warnings, the era of artificial intelligence has arrived to thrive. One hopes this era will manifest as an ode to those “who confer the greatest benefit” to humanity.”

Postscript.

As of this writing in late January 2025, the large language model-based AI tool, DeepSeek, was sending ripples with its seemingly insurmountable capabilities. Operable at far lower computational cost, DeepSeek significantly supersedes its closest competitors (46). DeepSeek’s unveiling led to major market upheavals and catapulted AI into yet another paradigm shift.

References

- M. von Zedtwitz, T. Gutmann, and P. Engelmann, Research Policy, vol. 54, no. 1, p. 105150, Nov. 2024.

- J. Jumper et al., Nature, vol. 596, no. 7873, pp. 583–589, Jul. 2021

- W. D. Heaven, “Geoffrey Hinton tells us why he’s now scared of the tech he helped build,” MIT Technology Review, May 02, 2023

- W. S. McCulloch and W. Pitts, “A logical calculus of the ideas immanent in nervous activity,” The Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 115–133, Dec. 1943

- D.O. Hebb, The organization of behavior (Wiley & Sons, 1949)

- D. O. Hebb, “The Organization of Behavior,” Apr. 2005

- F. Rosenblatt, Principles of neurodynamics: Perceptrons and theory of brain mechanisms (Spartan Book, Washington D.C., 1962)

- M.L. Minsky and S.A. Papert, Perceptrons: An introduction to computational geometry (MIT Press, Cambridge, 1969)

- J. Lettvin, H. Maturana, W. McCulloch, and W. Pitts, “What the Frog’s Eye Tells the Frog’s Brain,” Proceedings of the IRE, vol. 47, no. 11, pp. 1940–1951, Nov. 1959

- J. J. Hopfield, “Two cultures? Experiences at the physics-biology interface,” Physical Biology, vol. 11, no. 5, pp. 053002–053002, Oct. 2014

- J. J. Hopfield, “Neural networks and physical systems with emergent collective computational abilities.,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 79, no. 8, pp. 2554–2558, Apr. 1982

- J. J. Hopfield, “Neurons with graded response have collective computational properties like those of two-state neurons,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 81, no. 10, pp. 3088–3092, May 1984

- S.E. Fahlman, G.E. Hinton and T.J. Sejnowski. In Proceedings of the AAAI-83 conference, pp. 109-113 (1983)

- D. E. Rumelhart, G. E. Hinton, and R. J. Williams, “Learning representations by back-propagating errors,” Nature, vol. 323, no. 6088, pp. 533–536, Oct. 1986

- Y. LeCun, B. Boer, J.S. Denker, D. Henderson, R.E. Howard, W. Hubbard and L.D. Jackel, Neural Comput. 1, 541 (1989)

- Y. LeCun, L. Bottou, Y. Bengio and P. Haffner, Proc. IEEE 86, 2278 (1998).

- K. Fukushima, Biol. Cybern. 36, 193 (1980)

- G. E. Hinton, “Training Products of Experts by Minimizing Contrastive Divergence,” Neural Computation, vol. 14, no. 8, pp. 1771–1800, Aug. 2002

- P. Sharma and A. Singh, “Era of deep neural networks: A review,” 2017 8th International Conference on Computing, Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT), Jul. 2017

- B. K. Spears et al., “Deep learning: A guide for practitioners in the physical sciences,” Physics of Plasmas, vol. 25, no. 8, p. 080901, Aug. 2018

- J. V. Stone, “James V Stone - Books,” Sheffield.ac.uk, 2022

- C. B. Anfinsen, “Principles that Govern the Folding of Protein Chains,” Science, vol. 181, no. 4096, pp. 223–230, Jul. 1973

- P. B. Moore, W. A. Hendrickson, R. Henderson, and A. T. Brunger, “The protein-folding problem: Not yet solved,” Science, vol. 375, no. 6580, pp. 507–507, Feb. 2022

- R. Zwanzig, A. Szabo, and B. Bagchi, “Levinthal’s paradox.,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 89, no. 1, pp. 20–22, Jan. 1992

- B. Honig, “Protein folding: from the levinthal paradox to structure prediction,” Journal of Molecular Biology, vol. 293, no. 2, pp. 283–293, Oct. 1999

- J. T. Seffernick and S. Lindert, “Hybrid methods for combined experimental and computational determination of protein structure,” The Journal of Chemical Physics, vol. 153, no. 24, Dec. 2020

- “RCSB PDB: Homepage,” Rcsb.org. https://www.rcsb.org/

- Google DeepMind, “About Google DeepMind,” Google DeepMind. https://deepmind.google/about/

- A. W. Senior et al., “Improved Protein Structure Prediction Using Potentials from Deep Learning,” Nature, vol. 577, no. 7792, pp. 706–710, Jan. 2020

- J. Jumper et al., “Highly Accurate Protein Structure Prediction with Alphafold,” Nature, vol. 596, no. 7873, pp. 583–589, Jul. 2021

- C. Metz, “London A.I. Lab Claims Breakthrough That Could Accelerate Drug Discovery,” The New York Times, Nov. 30, 2020

- J. Abramson et al., “Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3,” Nature, vol. 630, no. 630, pp. 493–500, May 2024

- AlphaFold, “AlphaFold Protein Structure Database,” alphafold.ebi.ac.uk, 2022. https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/

- M. L. Hekkelman, I. de Vries, R. P. Joosten, and A. Perrakis, “AlphaFill: enriching AlphaFold models with ligands and cofactors,” Nature Methods, Nov. 2022

- F. Ren et al., “AlphaFold accelerates artificial intelligence powered drug discovery: efficient discovery of a novel CDK20 small molecule inhibitor,” Chemical Science, vol. 14, no. 6, 2023

- M. Struthers, R. P. Cheng, and B. Imperiali, “Design of a Monomeric 23-Residue Polypeptide with Defined Tertiary Structure,” Science, vol. 271, no. 5247, pp. 342–345, Jan. 1996

- B. I. Dahiyat and S. L. Mayo, “De Novo Protein Design: Fully Automated Sequence Selection,” Science, vol. 278, no. 5335, pp. 82–87, Oct. 1997

- B. Kuhlman, G. Dantas, G. C. Ireton, G. Varani, B. L. Stoddard, and D. Baker, “Design of a Novel Globular Protein Fold with Atomic-Level Accuracy,” Science, vol. 302, no. 5649, pp. 1364–1368, Nov. 2003

- Simons, K.T., Bonneau, R., Ruczinski, I. and Baker, D. "Ab initio protein structure prediction of CASP III targets using ROSETTA". Proteins, 37: 171-176, 1999

- https://www.ipd.uw.edu/

- “Solve Puzzles for Science | Foldit,” fold.it. https://fold.it/

- Horowitz, S., Koepnick, B., Martin, R. et al. Determining crystal structures through crowdsourcing and coursework. Nat Commun 7, 12549 (2016)

- H. Jo and D.-H. Park, “Effects of ChatGPT’s AI capabilities and human-like traits on spreading information in work environments,” Scientific Reports, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 7806, Apr. 2024

- S.-J. Chen et al., “Protein folds vs. protein folding: Differing questions, different challenges,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 120, no. 1, Dec. 2022

- V. Agarwal and A. C. McShan, “The power and pitfalls of AlphaFold2 for structure prediction beyond rigid globular proteins,” Nature Chemical Biology, Jun. 2024

- G. Conroy and S. Mallapaty, “How China created AI model DeepSeek and shocked the world,” Nature.com, Jan. 2025

- S. S. Haykin, Neural networks and learning machines. New York: Prentice Hall/Pearson, 2009

- Popular information. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Prize Outreach 2025. Sun. 23 Feb 2025. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/2024/popular-information