Gluten – Not For All Gluttons!

In “Gluten – Not for All Gluttons,” Shrestha Chowdhury takes readers on an informative journey exploring the science, history, and health impacts of gluten. Readers are introduced to gluten’s role in food, and the fascinating yet complicated composition of this protein complex found in wheat. From Celiac disease to gluten ataxia, this article provides a clear overview of gluten’s potential health impacts, as well as alternative solutions for those with sensitivities. The article is an engaging resource for readers curious about gluten or seeking to better understand the growing demand for gluten-free diets and products.

Shreya and Shruti are two good friends. They always stay together and often share food. One day, Shreya brought sandwiches for lunch to school, and she shared them with Shruti. They ate happily, but suddenly Shruti started feeling nauseous, and her stomach became upset. She remembered experiencing similar symptoms when she had a piece of paratha at home, though this time it felt more intense. Shreya took her to the medical room, where their favorite Doctor Kaka was present. Doctor Kaka asked Shruti many questions about her food habits and suggested a blood test. When the blood test results came back, it revealed that Shruti has ‘Celiac Disease’ and is allergic to gluten. Since they were still in school, they were hearing this for the first time. Curiously, they asked, “Doctor Kaka, can you tell us more about this gluten?” Doctor Kaka replied, “Sure, why not? Let’s start the story of gluten.”

Definition, origin, and whereabouts

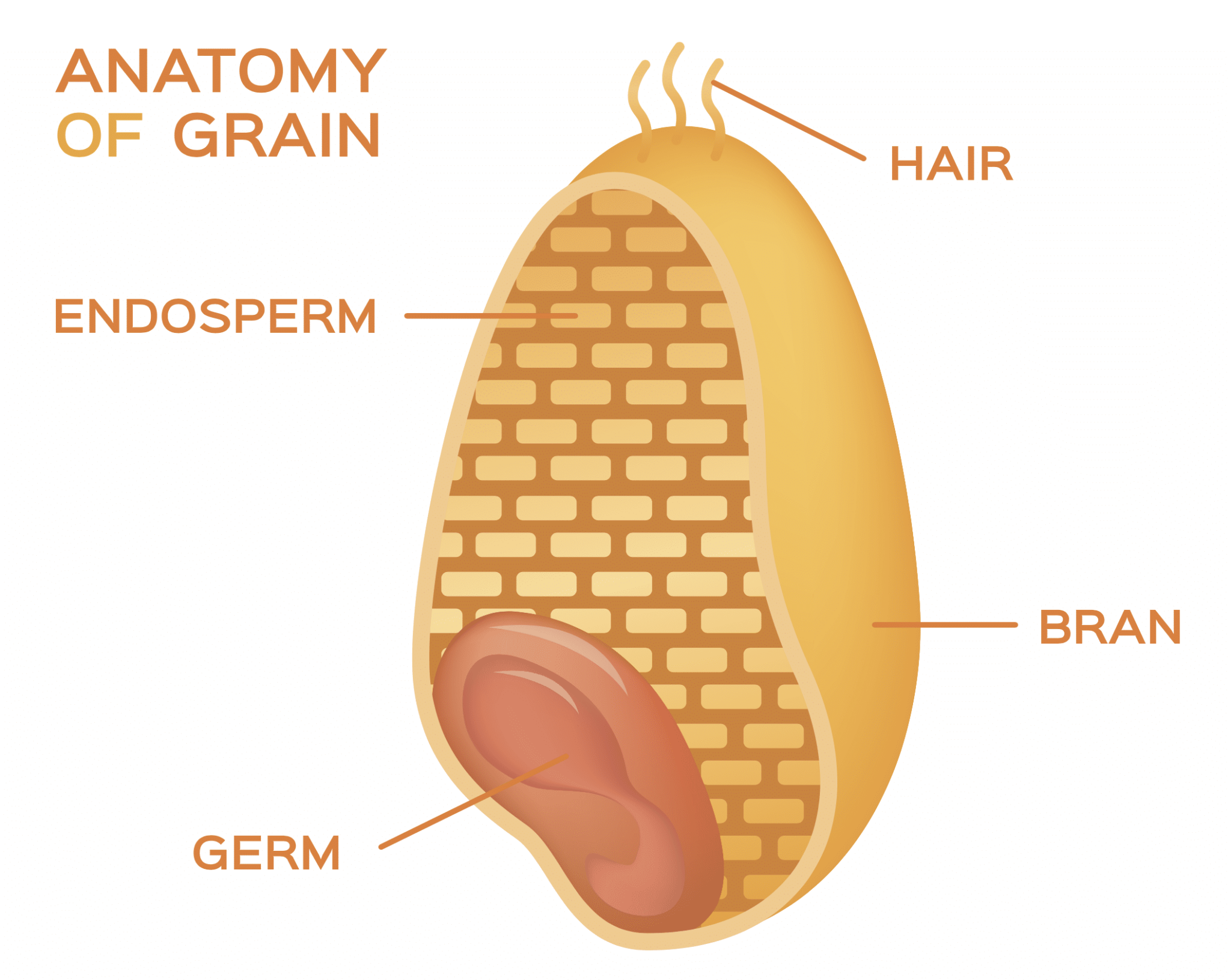

In simple terms, gluten is the rubbery substance that remains in wheat dough after the starch has been removed by washing it with water or a brine solution. Technically, gluten is a complex mix of hundreds of different proteins found in wheat and similar grains, like rye, barley, and oats. More specifically, these storage proteins are located in the endosperm of wheat kernels, where they help with future seed germination. Additionally, factors such as the type of wheat, the time of harvest, and the growing location all influence the amount of gluten present in the grain.

Fig 1. MYCIN: An early AI system that assists doctors in diagnosing infectious diseases and suggesting treatments by using a set of rules and logical reasoning (inference engine).

Fig 1. MYCIN: An early AI system that assists doctors in diagnosing infectious diseases and suggesting treatments by using a set of rules and logical reasoning (inference engine).

Discovery of glutens

One of the first proteins to be investigated scientifically was wheat gluten. Jacopo Beccari, a chemical professor at the University of Bologna, carried out the first such investigation in 1745. Prior to the 1970s, when gel electrophoresis was invented, Dr. T. B. Osborne, a plant protein chemist from Connecticut, was able to successfully extract proteins from a range of seeds in several solvents with different polarities between 1886 and 1928. His method, which is being used today, is called the Osborne fractionation.

The four protein fractions identified by this method are albumins, which are soluble in water, globulins, which are soluble in diluted saline, prolamins, which are soluble in 60–70% alcohol, and glutenins, which are insoluble in other solvents but can be extracted in alkali. During the extraction procedure, Dr. T.B. Osborne discovered a high concentration of amino acids, such as proline, in a particular class of protein, which he named Prolamins. He also went on to identify the different prolamin subclasses according to the grains’ origins. Gliadin in wheat, hordein in barley, secalin in rye, zein in maize, and so on are other examples.

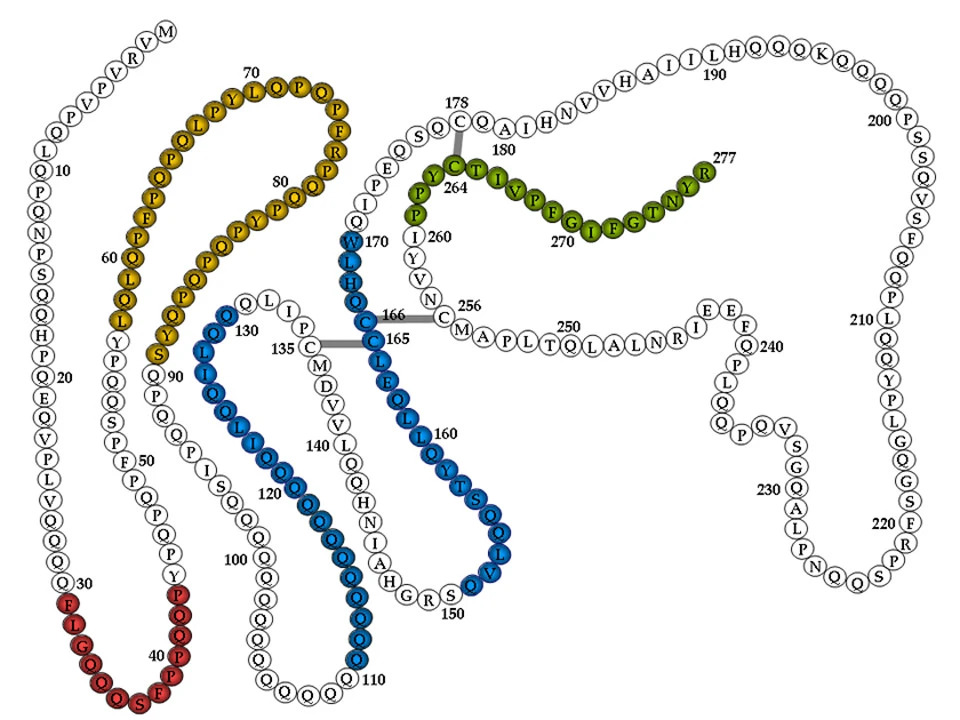

Components of gluten: gliadins and glutenins

In simple terms, gluten is primarily made up of two proteins: gliadins and glutenins, collectively known as prolamins. But how are these proteins produced inside a wheat grain? The genes responsible for synthesizing gluten proteins in developing wheat grains include the Gli-1 and Gli-2 loci, which code for gliadin proteins, and the Glu-1 and Glu-3 loci, which code for glutenin polypeptides. To understand how glutenins are synthesized and developed, we need to explore the underlying chemistry of their polypeptide production.

Fig 1. MYCIN: An early AI system that assists doctors in diagnosing infectious diseases and suggesting treatments by using a set of rules and logical reasoning (inference engine).

Fig 1. MYCIN: An early AI system that assists doctors in diagnosing infectious diseases and suggesting treatments by using a set of rules and logical reasoning (inference engine).

On a molecular level, gliadins are monomeric proteins with molecular weights (MW) ranging from approximately 28,000 to 55,000. In contrast, glutenins are polymers, particularly composed of high molecular weight (HMW) subunits, with weights varying from about 67,000 to over 88,000. Gliadins are further classified into three main types: α/β-, γ-, and ω-gliadins. The distribution of these types varies based on wheat genotype and environmental factors like climate, soil, and fertilization. Typically, α/β- and γ-gliadins are more abundant than ω-gliadins in the wheat grain.

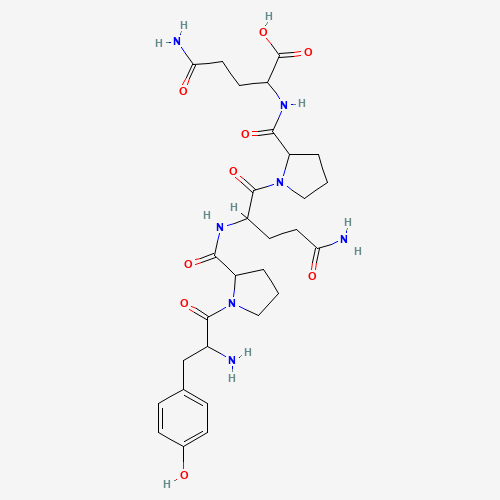

Closer examination reveals that gliadin proteins are composed almost entirely of repetitive sequences rich in glutamine and proline (such as PQQPFPQQ [2] ). Among the gliadins, α/β- and γ-gliadins share similar molecular weights and have lower amounts of glutamine and proline compared to ω-gliadins. In contrast, glutenins consist of both high molecular weight (HMW) and low molecular weight (LMW) subunits, with the LMW glutenin subunits (LMW-GS) being truncated forms of their HMW counterparts. LMW-GS account for approximately 20% of the total gluten proteins. These LMW subunits are similar to α/β- and γ-gliadins in both molecular weight and amino acid composition.

Fig 1. MYCIN: An early AI system that assists doctors in diagnosing infectious diseases and suggesting treatments by using a set of rules and logical reasoning (inference engine).

Fig 1. MYCIN: An early AI system that assists doctors in diagnosing infectious diseases and suggesting treatments by using a set of rules and logical reasoning (inference engine).

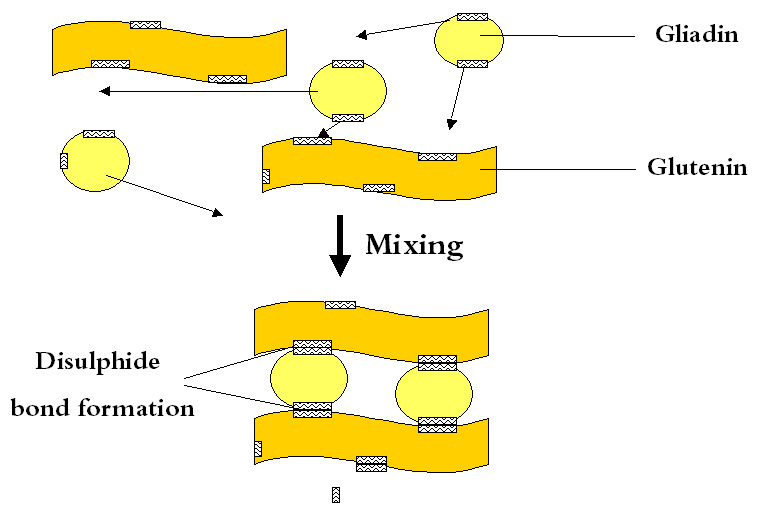

As HMW-GS does not occur in flour and dough as monomers, it is generally assumed that they form interchain disulfide bonds. Fun fact, the largest polymers termed ‘glutenin macropolymer (GMP) make the greatest contribution to dough properties and their amount in wheat flour (E20–40 mg/g) is strongly correlated with dough strength and loaf volume.

Polymer chemistry in glutens

The study of gluten polymers is especially important in bread making, as bread is a staple food in many cultures worldwide. Gluten proteins are highly hydrophobic, meaning they tend to bond more readily with lipids than with water. In dough, hydrated gliadins and glutenins behave differently: gliadins are less elastic and less cohesive, contributing mainly to the dough’s viscosity and extensibility. In contrast, hydrated glutenins are both cohesive and elastic, providing dough with its strength and elasticity. In simple terms, gluten acts as a two-part adhesive, where gliadins function as a “solvent” for the glutenins, supporting the formation of the dough’s structure.

Fig 1. MYCIN: An early AI system that assists doctors in diagnosing infectious diseases and suggesting treatments by using a set of rules and logical reasoning (inference engine).

Fig 1. MYCIN: An early AI system that assists doctors in diagnosing infectious diseases and suggesting treatments by using a set of rules and logical reasoning (inference engine).

Glutenin subunits through hydrogen bonds, form large three-dimensional networks via inter-chain disulfide bonds. These bonds interact with gliadins and with other glutenin networks. Throughout the processing of bread, the condition of large glutenin polymers is characterized by three competitive redox reactions

- the oxidation of free SH groups (thiol) in the peptide chains which support polymerization

- the presence of ‘terminators’ that stop polymerization and,

- SH/SS interchange reactions between glutenins and thiol compounds such as glutathione that depolymerize polymers.

Notably, the overriding importance of disulfide bonds can be demonstrated by the addition of reducing agents weakening dough and of thiol-blocking or oxidizing agents strengthening dough.

Fig 1. MYCIN: An early AI system that assists doctors in diagnosing infectious diseases and suggesting treatments by using a set of rules and logical reasoning (inference engine).

Fig 1. MYCIN: An early AI system that assists doctors in diagnosing infectious diseases and suggesting treatments by using a set of rules and logical reasoning (inference engine).

On the other hand, oxygen is found to be crucial for the formation of large glutenin polymers during the mixing of the dough. Oxidizing agents such as potassium bromate, potassium iodate, and L-ascorbic acid exhibit the same effect as atmospheric oxygen. Finally, the baking process leads to dramatic changes in the glutenin structure and functionality. For example, extractability in the urea or SDS is strongly reduced and most cysteine-containing α, β- and γ-gliadins are covalently bound to glutenin polymers after baking. Disulphide interchange reactions between gliadins and glutenins have been also postulated to be involved in the heat-induced effects.

To put it succinctly, gluten proteins are one of the most complicated protein networks seen in nature because of their many distinct parts, varying sizes, and unpredictability brought on by technologies, growing environments, and genetics. They are crucial in establishing wheat’s distinct rheological dough characteristics and baking quality.

Fig 1. MYCIN: An early AI system that assists doctors in diagnosing infectious diseases and suggesting treatments by using a set of rules and logical reasoning (inference engine).

Fig 1. MYCIN: An early AI system that assists doctors in diagnosing infectious diseases and suggesting treatments by using a set of rules and logical reasoning (inference engine).

As their curiosity grew, Shreya and Shruti questioned, “But Kaka, why are only some of us gluten intolerant?” Doctor Kaka continued with this story.

Harmful effects

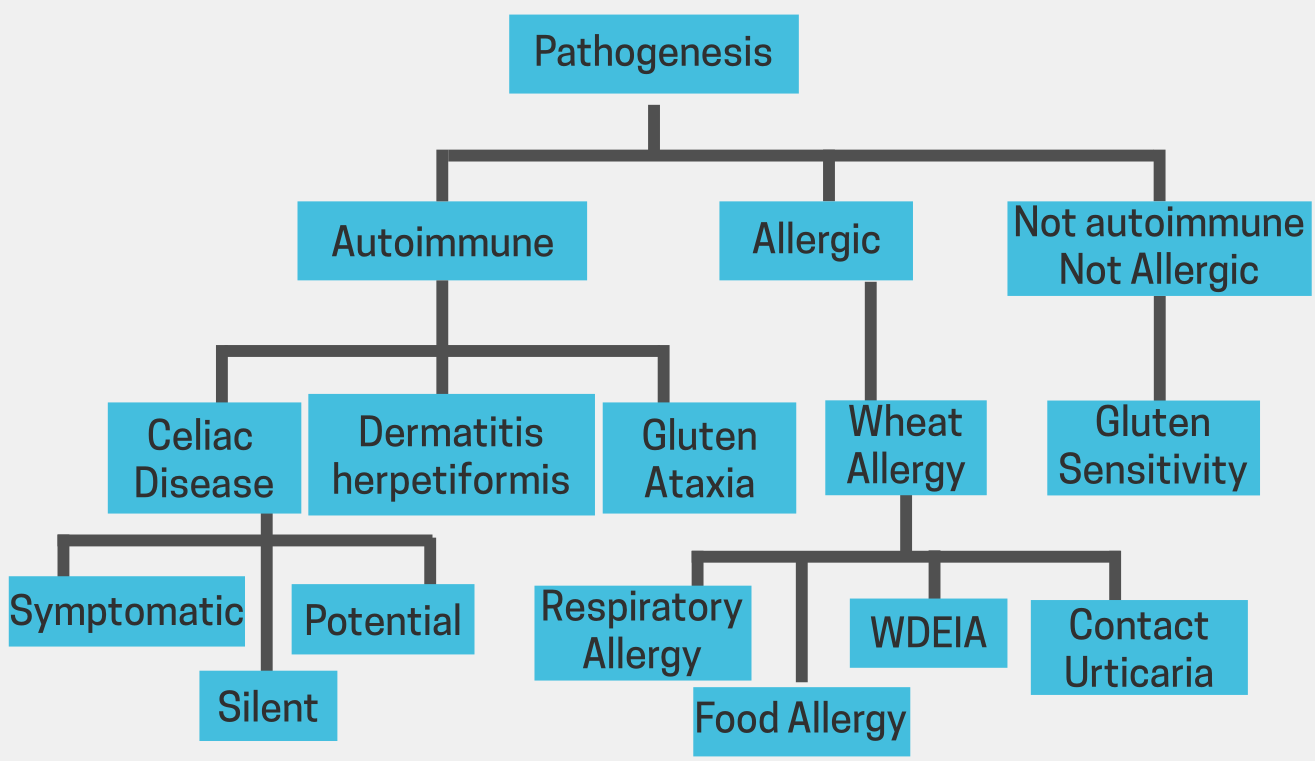

It is unfortunate that some individuals are unable to consume gluten-based products due to various health conditions. Gluten can trigger adverse reactions in susceptible people.

Celiac Disease is a serious autoimmune disorder where gluten consumption triggers an immune response that damages the small intestine. This damage can lead to malabsorption of nutrients, leading to symptoms such as diarrhea, abdominal pain, fatigue, and weight loss.

Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity (NCGS) is a condition where individuals experience symptoms similar to celiac disease, but without the intestinal damage. These symptoms may include digestive issues, fatigue, headaches, and skin problems.

Gluten Ataxia is a neurological disorder caused by gluten exposure. It affects the cerebellum, a part of the brain responsible for coordination and balance. Symptoms can include clumsiness, difficulty walking, and slurred speech.

Dermatitis Herpetiformis is a skin condition characterized by itchy, blistering skin rashes. It is often associated with celiac disease and improves with a gluten-free diet.

Fig 1. MYCIN: An early AI system that assists doctors in diagnosing infectious diseases and suggesting treatments by using a set of rules and logical reasoning (inference engine).

Fig 1. MYCIN: An early AI system that assists doctors in diagnosing infectious diseases and suggesting treatments by using a set of rules and logical reasoning (inference engine).

While the exact mechanisms by which gluten triggers these conditions are not fully understood, genetic factors and immune system responses play significant roles. In individuals with celiac disease, for example, specific genes increase the likelihood of developing the condition. When these individuals consume gluten, their immune system mistakenly identifies it as a harmful substance, triggering an immune response that damages the small intestine. In non-celiac gluten sensitivity, the immune response is different but can still cause symptoms like digestive discomfort, fatigue, and headaches. These immune-mediated responses lead to inflammation and tissue damage, which can impact nutrient absorption and overall health. For individuals with these conditions, a strict gluten-free diet is the only effective treatment.

Fig 1. MYCIN: An early AI system that assists doctors in diagnosing infectious diseases and suggesting treatments by using a set of rules and logical reasoning (inference engine).

Fig 1. MYCIN: An early AI system that assists doctors in diagnosing infectious diseases and suggesting treatments by using a set of rules and logical reasoning (inference engine).

What makes bread so tasty? Are there healthier alternatives?

Since the dawn of human civilization over 10,000 years ago, wheat has been a staple food. Bread, its primary form of consumption, is beloved for its texture and crunch, thanks to the unique viscoelastic properties of dough. However, gluten, a protein complex in wheat, can cause serious health issues for many. A gluten-free diet is often the preferred choice for these individuals. According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, gluten-free foods must contain less than 20 parts per million of gluten.

While a variety of gluten-free alternatives exist, they often fall short in terms of taste and texture. Gluten-free bread, for instance, can be dense, dry, and lacking in flavor. This is largely due to the absence of gluten, which provides elasticity and structure to dough. To compensate, manufacturers often use a combination of starches, fibers, and hydrocolloids, but these ingredients can impact the bread’s overall quality.

To improve the quality of gluten-free bread, researchers are exploring several strategies:

-

Mimicking Gluten’s Function: By carefully selecting and combining different ingredients, such as hydrocolloids, starches, and proteins, manufacturers can create doughs that mimic the properties of gluten-containing dough.

-

Enhancing Flavor and Aroma: The Maillard reaction, a chemical process that occurs during baking, contributes to the flavor and aroma of bread. By manipulating the ingredients and baking process, researchers can enhance the Maillard reaction in gluten-free bread.

-

Improving Texture: Enzymes, such as transglutaminase and proteases, can be used to modify the protein structure and improve the texture of gluten-free bread.

-

Leveraging Fermentation: Sourdough fermentation can enhance the flavor, aroma, and texture of gluten-free bread by introducing beneficial bacteria and yeast.

While gluten-free bread may not yet match the taste and texture of traditional wheat bread, ongoing research and innovation are bringing us closer to this goal. As scientists continue to delve deeper into the science of breadmaking, we can expect to see significant improvements in the quality of gluten-free products.

Fig 1. MYCIN: An early AI system that assists doctors in diagnosing infectious diseases and suggesting treatments by using a set of rules and logical reasoning (inference engine).

Fig 1. MYCIN: An early AI system that assists doctors in diagnosing infectious diseases and suggesting treatments by using a set of rules and logical reasoning (inference engine).

Is there a silver lining?

Overall, gluten-free bread is more expensive than traditional bread. However, the market for gluten-free products is steadily growing. Beyond human consumption, gluten finds applications in pet food. Additionally, it has non-edible uses, such as removing ink from waste paper, creating pressure-sensitive medical bandages and adhesives, solidifying waste oils, and forming biodegradable resins. Gluten films also protect food from moisture and bacteria. Therefore, contrary to some media portrayals, gluten is not inherently harmful.

Gluten, though discovered three hundred years ago, has only recently become a focal point of attention due to the growing awareness of various gluten-related disorders. Fortunately, we no longer live in a time devoid of gluten-free alternatives. Today, the market offers a plethora of such options, although there’s still room for improvement in their taste. Nevertheless, the demand for gluten-free alternatives has opened up new business opportunities. So, cheer up your gluten-sensitive friends! It’s not far-fetched to imagine a future where new wheat cultivars are developed, free from the toxic polypeptides found in gluten. Of course, achieving this milestone requires a deep understanding of protein folding, both experimentally and theoretically.

References

- J. R. Biesiekierski, “What Is gluten?,” Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, vol. 32, no. S1, pp. 78–81 (2017)

- P. Shewry, "What Is Gluten—Why Is It Special?", Frontiers in Nutrition, vol. 6, no. 101 (2019)

- Pubchem, National Library of Medicine

- F. Rasheed et al., “Structural architecture and solubility of native and modified gliadin and glutenin proteins: non-crystalline molecular and atomic organization,” RSC Adv., vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 2051–2060 (2014)

- H. Wieser, “Chemistry of gluten proteins,” Food microbiology, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 115–9 (2007)

- Preichardt, Leidi & Gularte, M., “Gluten formation: Its Sources, composition and health effects”, Gluten: Sources, Composition and Health Effects. 55-70 (2013)

- M. Wang, T. van Vliet, and R. J. Hamer, “How gluten properties are affected by pentosans,”

- Journal of Cereal Science, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 395–402, (2004)

- Arch Gen Psychiatry Vol 39 March 1982

- L. Day, M. A. Augustin, I. L. Batey, and C. W. Wrigley, “Wheat-gluten uses and industry needs,” Trends in Food Science & Technology, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 82–90, (2006)

- F. Naqash, A. Gani, A. Gani, and F. A. Masoodi, “Gluten-free baking: Combating the challenges - A review,” Trends in Food Science & Technology, vol. 66, pp. 98–107 (2017)

- Vol. 79, Nr. 6, 2014 Journal of Food Science R1067

- Journal of Cereal Science 29, 103–107 (1999)

- Biotechnology 13, (1995)

- A. Sapone et al., “Spectrum of gluten-related disorders: consensus on new nomenclature and classification,” BMC Medicine, vol. 10, no. 1 (2012)

- Volta, U., De Giorgio, “R. New understanding of gluten sensitivity”, Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 9, 295–299 (2012)

- Miranda, J., Lasa, A., Bustamante, M.A. et al. “Nutritional Differences Between a Gluten-free Diet and a Diet Containing Equivalent Products with Gluten”, Plant Foods Hum Nutr 69, 182–187 (2014)

- The Cerebellum, Clinical Neuroanatomy: A Neurobehavioral Approach, Springer Science + Business Media (2008)

- Hadjivassiliou M et al., “Gluten sensitivity: from gut to brain”. Lancet Neurol (2010)

- LWT - Food Science and Technology 63 (2015) 706-713

- Amy, “Guide to Wheat Flour”, (2020)

- V. D. Capriles, F. G. dos Santos, and J. A. G. Arêas, “Gluten-free breadmaking: Improving nutritional and bioactive compounds,” Journal of Cereal Science, vol. 67, pp. 83–91, (2016)