Revolutionising Biology with Artificial Intelligence

Suryadip and Tathagata offer an engaging exploration of how AI is transforming biological sciences. From the early days of rule-based AI to cutting-edge deep learning applications like AlphaFold, this article traces the evolution of AI’s role in biology. It highlights AI’s power in solving complex problems such as protein folding, drug discovery, and genomics. With groundbreaking examples like DeepVariant and DrugGPT, readers will gain insight into AI’s monumental impact on research and healthcare. Dive into the future of biology where data meets innovation!

Artificial Intelligence (AI), the talk of the town right now, has revolutionised various fields and the life sciences is no exception. Before we go further into how exactly AI is changing the course of life as we speak, let us get up to speed with a few concepts.

Marvin Minsky defined artificial intelligence as “the science of making machines do things that would require intelligence if done by men”. Ideally one would apply AI for problems where it is impossible to define consolidated rules. A very simple example could be the spam filters in our emails. It is virtually impossible for programmers to identify a set of rules to identify all types of spam. This is because these messages constantly keep evolving with newer wordings and patterns. Therefore AI models are trained using examples of both spam and legitimate emails to help identify subtle patterns and adapt to the new spam techniques over time. This is exactly why biology is such a beautiful candidate for AI applications, owing to its inherent complexity.

Machine Learning (ML) is a subset of AI that focuses on the development of algorithms that allow computers to learn from and make predictions based on data. Deep Learning (DL) is a further subset of ML that utilises neural networks (inspired from, but in no way similar to biological neurons) with many layers (hence “deep”) to analyse various factors of data (especially non-linearity). These two branches of AI are the most prevalently used in biology to date.

Early Days: From Symbolic AI to ML and DL

It all dates back to the 1950s, when Alan Turing proposed the concept of machines being able to simulate any form of human reasoning through algorithmic approaches [1] . As a result, during the early years, AI was largely rule-based (aka Symbolic AI) which was based on logical representations of the world. This led to the birth of expert systems, which used knowledge bases of rules to solve specific problems. One such expert system was called MYCIN (1978) (Fig 1) [2] . It was developed by Edward Shortliffe as part of his doctoral dissertation, under the guidance of Bruce G. Buchanan, Stanley N. Cohen, and others at Stanford University. MYCIN was used to identify the bacteria causing severe bacterial infections like meningitis and bacteremia and to subsequently recommend appropriate antibiotics and their dosages according to the patient’s body weights.

The advent of the internet and a substantial increase in computational power led to the growth of enormous volumes of data. This led to the next big break in the early 2000s in the form of Machine Learning algorithms. These algorithms were able to learn from data and perform tasks such as predicting outcomes, classifying objects or clustering them based on similarity, as opposed to following predefined rules. Further, the introduction of DL opened even more avenues and a whole new range of applications in tasks such as image processing, signal processing, natural language processing etc. Nowadays, AI has extended its branches into any and all fields of human endeavour with an especially serial impact on healthcare, medicine, and biological research.

AI and the era of Structural Biology

Applications of AI for solving complex problems in the life sciences can be dated back to the late 1990s. This was the era of structural biology. Proteins are the molecular machines that carry out all biological processes in a cell, and their structure dictates their function [3] Therefore, scientists were devoted to finding solutions to identify and manipulate said protein structures.

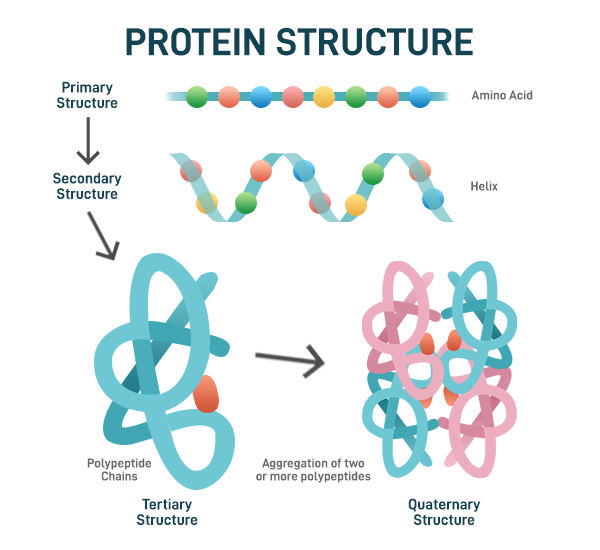

Proteins are unbranched polymers constructed from 22 standard amino acids. They have four levels of structural organisation (primary, secondary, tertiary and quaternary). Primary structure refers to the amino acid sequence that is specified by the genetic information contained within the DNA. As the polypeptide folds, it forms certain localised arrangements of adjacent amino acids that constitute of the secondary structures (mainly in the form of ɑ-helices and 𝛃-sheets). Tertiary structure refers to the three-dimensional shape of a protein formed by the overall folding of the polypeptide chain onto itself. It results from interactions among the various R groups (side chains) of the amino acids, including hydrogen bonds, ionic bonds, van der Waals forces, and disulfide bridges. A protein quaternary structure arises when two or more polypeptide chains (subunits) come together to form a larger functional protein complex. The arrangement and interaction of these subunits are crucial for the protein’s function. Together, these levels of structure are essential for a protein’s biological activity and functionality (Fig 2) [4] .

Fig 2. Protein Structure Hierarchy

Fig 2. Protein Structure Hierarchy

During this time, X-Ray Crystallography and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (NMR-Spec) were heavily being used to determine the complicated 3D structures of proteins. Due to the complexity of the protocols associated with these techniques coupled with low success rate, scientists started to look for more feasible solutions. In 1990, the labs of Ross King (Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden) and Michael Sternberg (Imperial College London) came up with an ML program called PROMIS (PROtein Machine Induction System) that could generalise rules to characterise the relationship between primary and secondary structures of globular proteins. These rules could further be used to predict unknown secondary structures from a known primary structure of a protein [5] . Quantitative Structure Activity Relationship Modeling (QSAR) is an extensively used approach in drug design and discovery that devises mathematical models connecting the biological activity of these drugs to their complex chemical features [6] . In 1994, the pair of King and Sternberg modelled the QSAR of a series of drugs using a technique called Inductive Logic Programming (ILP) [7] . ILP is a machine learning technique that uses a combination of logic programming and data driven decision making [8] . With the application of ILP, they were able to elucidate complex and interpretable patterns within the data that might have originally been overlooked while investigating using traditional statistical approaches.

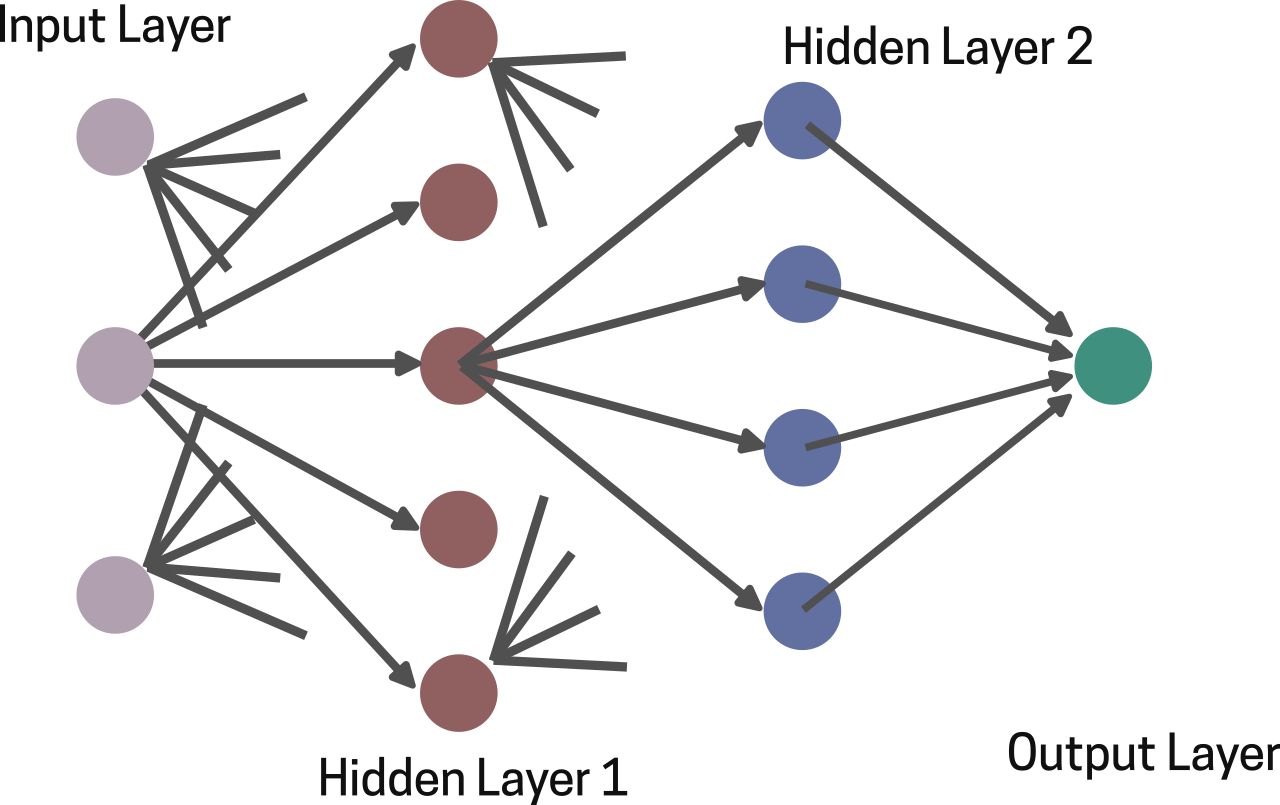

Further, in the year 2000, the lab of R. Casadio used a class of artificial neural networks known as a Feed Forward Network (FFN), to predict protein folding and structure from only their corresponding amino acid sequence [9] . A feed forward network is basically composed of several layers of interconnected computational units called neurons (inspired from biological neurons) (Fig 3). Each neuron in a layer has a weight factor (think of it as a scalar value that denotes the neuron’s contribution to the output) associated with it and receives numerical inputs from other neurons in the previous layer, processes them by applying a weighted sum and an activation function, and passes the result to the neurons in the next layer. This allows the network to model complex, non-linear patterns [10] . Therefore, hypothetically speaking, the non-linear relationship between a protein’s primary amino acid sequence and its folded 3D structure can be modelled efficiently using this FFN. By capturing these subtle relationships, FFNs provided insights into how specific sequence motifs correspond to structural motifs underscoring the massive applications of AI in the field of structural biology.

Fig 3. A 4 layer FFN with 1 input layer, 2 hidden layers and 1 output layer

Fig 3. A 4 layer FFN with 1 input layer, 2 hidden layers and 1 output layer

Genomics and the Rise of AI

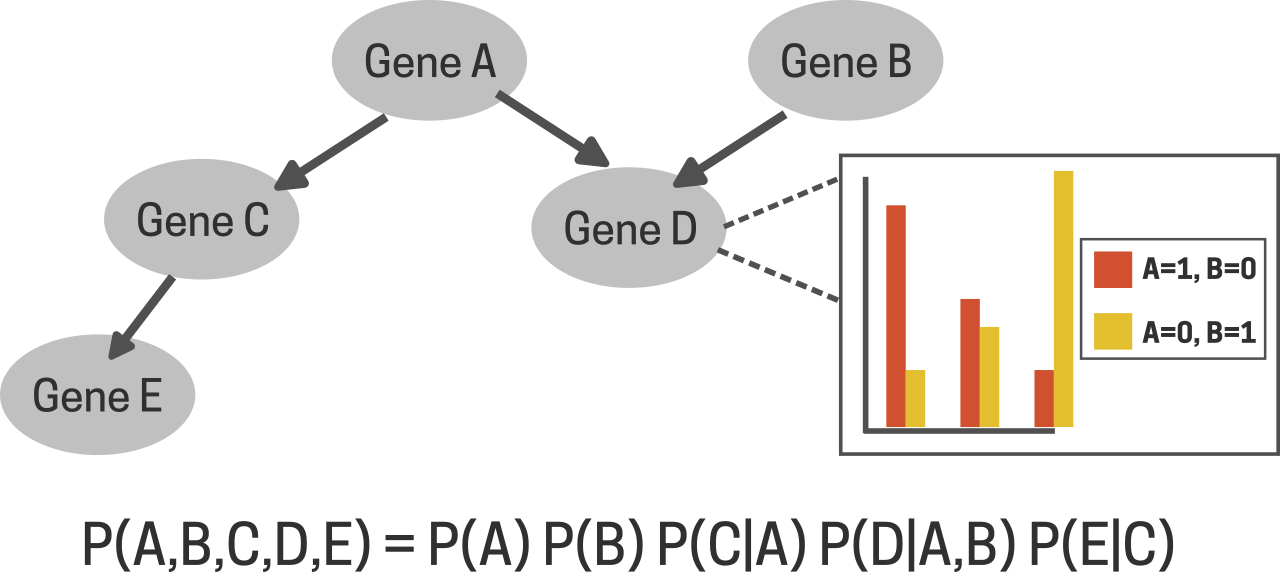

The Human Genome Project (HGP) was an international research initiative with the goal of sequencing the entire human genome. Launched in 1990, the HGP was completed in 2003 with the submission of the 1st draftt of the human genome. Its goals included identifying all human genes, determining their sequences, and exploring the functions of these genes. The project has had profound implications for medicine, genetics, and our understanding of human biology. Following that, in the early 2000s, vast amounts of genomic data were generated which warranted the need for advanced analytical methods. Michael Schatz and his colleagues applied ML techniques to genome assembly, enhancing the efficiency of sequence alignment [11] . In 2004, David Heckerman demonstrated the use of Bayesian Networks, a type of probabilistic graphical model, to predict gene functions from microarray data [12] . Bayesian networks as the name suggests were based on the concept of Bayesian statistics that provides a way to update the probability of a hypothesis as new evidence becomes available, forming the foundation of Bayesian inference [13] . Heckerman used microarray data that contains information about the activity level (how active or inactive the gene is) of thousands of genes across specific conditions. In his approach, variables such as the genes were represented as nodes and the probabilistic dependencies between them as edges, making them particularly effective for capturing complex, uncertain relationships (Fig 4). This enabled Heckerman to identify the complex crosstalks between genes and their functional relationships to each other based on expression patterns.

Fig 4. Bayesian Network for gene interaction studies. Each node is a random variable (gene) indicating the mRNA level expression of that gene. The arrows indicate direct probabilistic relationships. See [28].

Fig 4. Bayesian Network for gene interaction studies. Each node is a random variable (gene) indicating the mRNA level expression of that gene. The arrows indicate direct probabilistic relationships. See [28].

Through these networks, it became possible to model how changes in the expression of one gene influence others, uncovering hidden dependencies and regulatory mechanisms [12] . In 2016, Angermueller’s lab utilised Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), which were traditionally used to process image data, on DNA sequences to predict gene expression, with accuracies comparable to traditional methods [14] . CNNs are comprised of layers of neurons that utilise convolutional filters to capture local patterns and hierarchical features. A convolutional filter is a matrix of weights that is slid along the entire sequence effectively learning hidden patterns and features from them, much like detecting edges or textures within an image which is nothing but a sequence of pixel values. Moreover, since the same filter is being slid along the entire sequence, it can capture both local and global dependencies among these sequences potentially identifying important motifs such as transcription factor binding sites [15] .

Fig 5. CNN for gene prediction. An ORF is first one-hot encoded and then fed into a CNN-MGP model chosen based on its GC content. The model has 6 layers: a convolutional layer with 64 filters (window size of 21), followed by a max-pooling layer (pool size of 2), another convolutional layer with 200 filters (window size of 21), and another max-pooling layer (pool size of 2). The output is flattened into a 1D vector, which is passed through a fully connected layer with 128 neurons. Finally, the output layer produces a probability indicating whether the sequence represents a gene.

Fig 5. CNN for gene prediction. An ORF is first one-hot encoded and then fed into a CNN-MGP model chosen based on its GC content. The model has 6 layers: a convolutional layer with 64 filters (window size of 21), followed by a max-pooling layer (pool size of 2), another convolutional layer with 200 filters (window size of 21), and another max-pooling layer (pool size of 2). The output is flattened into a 1D vector, which is passed through a fully connected layer with 128 neurons. Finally, the output layer produces a probability indicating whether the sequence represents a gene.

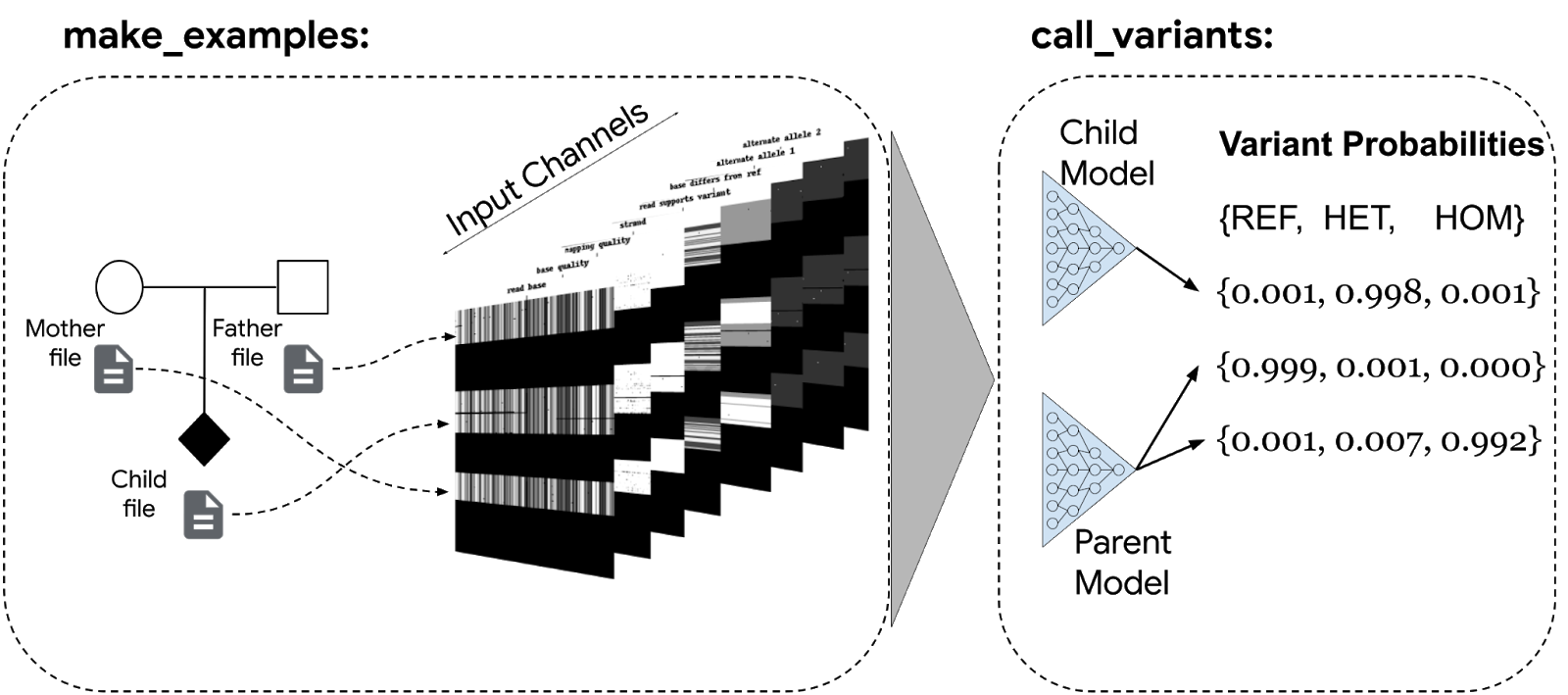

Most recently in 2018, Google developed a DL based tool called the DeepVariant that employs a deep CNN architecture to identify variants in DNA sequences, outperforming traditional state of the art tools and pipelines such as GATK and Augustus [17] (Fig 6).

AI in Biomedical Imaging, Diagnostics and Drug Discovery

CNNs being at the forefront of computer vision at the time also inspired biologists to actually use them for biomedical image analysis and predictive modelling based on biomedical image data. In 2017, Andre Esteva and his colleagues developed a CNN model that could diagnose and differentiate skin cancer from other standard skin lesions with accuracy comparable to dermatologists by analysing dermoscopic images [18] . U-Net, a CNN architecture developed by Olaf Ronneberger, is widely used nowadays for segmenting biological images, especially in the field of histopathology which is the study of tissue changes and diseases at the microscopic level, often involving the examination of biopsies to diagnose conditions (see Fig. 5). It has shown remarkable performance in analysing histological slides accurately diagnosing cancerous tissues, thereby improving patient outcomes [19] .

Fig 6. Google DeepVariant Workflow. Input data, such as genomic reads, are processed to extract features like base quality, mapping quality, and strand information. These features are transformed into tensors (format compatible with neural networks) and fed into deep neural networks, enabling accurate identification of genomic variants.

Fig 6. Google DeepVariant Workflow. Input data, such as genomic reads, are processed to extract features like base quality, mapping quality, and strand information. These features are transformed into tensors (format compatible with neural networks) and fed into deep neural networks, enabling accurate identification of genomic variants.

ML has contributed significantly towards the drug discovery space as well, including applications in drug target identification, biomarker discovery, QSAR modelling and predicting efficacy of drug candidates, thereby accelerating the drug development process. Biomarker discovery—the identification of measurable indicators such as genes, proteins, or metabolites linked to specific diseases—has benefited from ML’s ability to analyze complex datasets and uncover subtle patterns, aiding in personalized medicine and early diagnosis [20] . Yuesen Li and his colleagues in 2023 developed DrugGPT focusing on chemical space exploration of protein ligand complexes, which refers to navigating the enormously complex universe of chemical compounds to identify potential drug molecules targeting specific proteins [21] .

A Leap Forward with AlphaFold

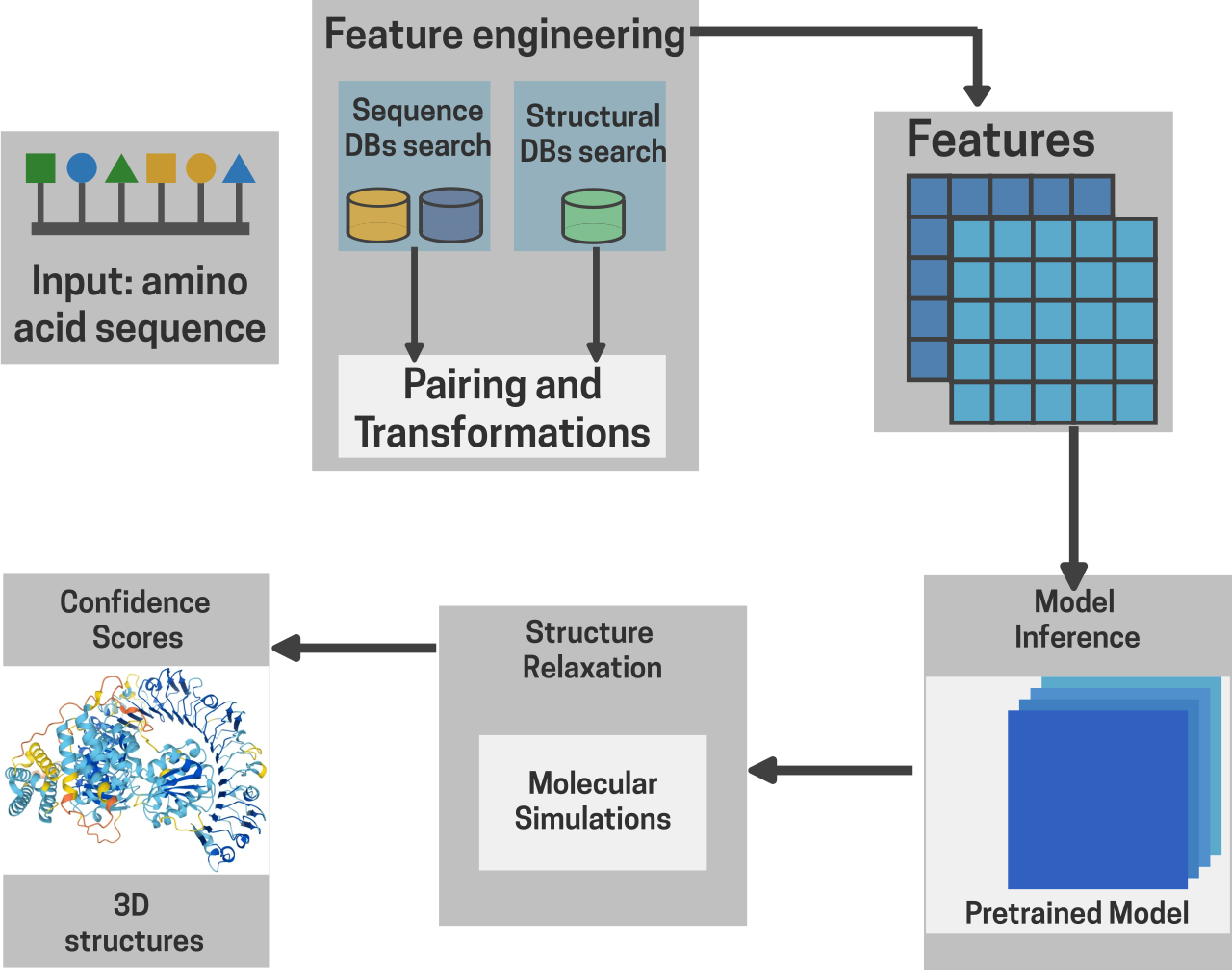

In the realm of structural biology, we have come a long way as well. In the year 2021, John Jumper and his team at Google Deepmind rocked the world of biology with their groundbreaking model called AlphaFold. AlphaFold redefined the age-old problem of predicting protein 3D structures from just their amino acid sequence information. It uses a pseudo-bayesian genetic algorithm based deep neural network to model the physical and geometric properties of proteins from just their amino acid sequence and gives highly accurate 3D structures of proteins solving the bottleneck of time, complexity and low success rate associated with methods like X-ray crystallography, NMR-spec and Cryo Electron microscopy (Cryo-EM) [22] . In 2024, Jumper was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for AlphaFold emphasizing the importance and relevance of AI in biology even further.

Fig 7. AlphaFold Inference Workflow

Fig 7. AlphaFold Inference Workflow

Biology Inspiring AI models

Interestingly enough, the relationship between AI and biology has been quite symbiotic. It is not only biology that has gained from AI models, biology has also inspired AI models on more than one occasion. The most prevalent of them all is actually that of the neural networks (the building blocks of DL). In 1943, Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts built a mathematical model of the functioning of a single neuron [23] . Taking inspiration from human perception, Frank Rosenbahlt modelled the first neural network in 1957 that was able to recognize some handwritten symbols effectively and could model basic logical operations such as AND and OR gates. This was known as the Perceptron and it would lay the foundation for further development of DL and neural network architectures [24] .

Our immune system only allows lymphocytes, that recognize certain antigens, to be cloned and proliferated with such identical antigenic receptors. This phenomenon known as clonal selection presents itself as a learning problem driven by context (antigen) and an appropriate response. This led to the invention of the Artificial Immune System, a class of computationally intelligent, rule-based machine learning systems, inspired by the intricacies of the immune system of vertebrates [25] . Akin to their living counterparts these models excel in recognizing something presented to it as an “antigen” and take the most appropriate response making them ideal for applications such as antiviruses and anti-spams.

Towards the Future

The synergy between AI and biology has set the stage for groundbreaking discoveries and innovations. From protein structure prediction with AlphaFold to the use of neural networks in genomics and drug discovery, biology has been transformed into a data-driven, predictive and multi-disciplinary branch of science. Whether it’s predicting disease, designing drugs, or deciphering the mysteries of life at the molecular level, AI is now an indispensable tool in every biologist’s toolkit. So, if you’re curious, now’s the time to dive into this captivating intersection of science and technology—where the future of biology is being driven by AI.

References

- Akman, V., & Blackburn, P. (2000). Alan Turing and artificial intelligence. Journal of Logic, Language, and Information, 391-395.

- Shortliffe E. H. (1977). Mycin: A Knowledge-Based Computer Program Applied to Infectious Diseases. Proceedings of the Annual Symposium on Computer Application in Medical Care, 66–69.

- Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, et al. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 4th edition. New York: Garland Science; 2002. Analyzing Protein Structure and Function

- The Protein Folding Problem: A Structural Perspective, S. J. Baker et al. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2006

- King, R. D., & Sternberg, M. J. (1990). Machine learning approach for the prediction of protein secondary structure. Journal of molecular biology, 216(2), 441–457.

- Tandon, H., Chakraborty, T., & Suhag, V. (2019). A concise review on the significance of QSAR in drug design. Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, 4(4), 45-51.

- Sternberg, M. J., King, R. D., Lewis, R. A., & Muggleton, S. (1994). Application of machine learning to structural molecular biology. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 344(1310), 365-371.

- Cropper, A., & Dumančić, S. (2022). Inductive logic programming at 30: a new introduction. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research, 74, 765-850.

- Casadio, R., Compiani, M., Fariselli, P., Jacoboni, I., & Martelli, P. L. (2000). Neural networks predict protein folding and structure: artificial intelligence faces biomolecular complexity. SAR and QSAR in environmental research, 11(2), 149–182.

- Svozil, D., Kvasnicka, V., & Pospichal, J. (1997). Introduction to multi-layer feed-forward neural networks. Chemometrics and intelligent laboratory systems, 39(1), 43-62.

- Initial Sequencing and Analysis of the Human Genome Authors: International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium :Nature 2001

- Schatz, M. C., Delcher, A. L., & Salzberg, S. L. (2010). Assembly of large genomes using second-generation sequencing. Genome research, 20(9), 1165–1173.

- Heckerman, D. (1998). A Tutorial on Learning with Bayesian Networks. In: Jordan, M.I. (eds) Learning in Graphical Models. NATO ASI Series, vol 89. Springer, Dordrecht.

- Stephenson, Todd Andrew. An introduction to Bayesian network theory and usage. (2000).

- Angermueller, C., Pärnamaa, T., Parts, L., & Stegle, O. (2016). Deep learning for computational biology. Molecular systems biology, 12(7), 878.

- MICCAI 2015: 18th international conference, Munich, Germany, October 5-9, 2015, proceedings, part III 18 (pp. 234-241). Springer International Publishing.

- Li, Z., Liu, F., Yang, W., Peng, S., & Zhou, J. (2021). A survey of convolutional neural networks: analysis, applications, and prospects. IEEE transactions on neural networks and learning systems, 33(12), 6999-7019

- Poplin, R., Chang, P. C., Alexander, D., Schwartz, S., Colthurst, T., Ku, A., ... & DePristo, M. A. (2018). A universal SNP and small-indel variant caller using deep neural networks. Nature biotechnology, 36(10), 983-987.

- Esteva, A., Kuprel, B., Novoa, R. A., Ko, J., Swetter, S. M., Blau, H. M., & Thrun, S. (2017). Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. nature, 542(7639), 115-118.

- Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P., & Brox, T. (2015). U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention

- Vamathevan, J., Clark, D., Czodrowski, P., Dunham, I., Ferran, E., Lee, G., ... & Zhao, S. (2019). Applications of machine learning in drug discovery and development. Nature reviews Drug discovery, 18(6), 463-477.

- Li, Y., Gao, C., Song, X., Wang, X., Xu, Y., & Han, S. (2023). DrugGPT: A GPT-based strategy for designing potential ligands targeting specific proteins. bioRxiv, 2023-06.

- Jumper, J., Evans, R., Pritzel, A., Green, T., Figurnov, M., Ronneberger, O., ... & Hassabis, D. (2021). Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. nature, 596(7873), 583-589

- McCulloch, W. S., & Pitts, W. (1943). A logical calculus of the ideas immanent in nervous activity. The bulletin of mathematical biophysics, 5, 115-133.

- Rosenblatt, F. (1957). The perceptron, a perceiving and recognizing automaton Project Para. Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory.

- Nicosia, G., Cutello, V., Bentley, P. J., & Timmis, J. (2004, September). Artificial immune systems. In Third International Conference, ICARIS (Vol. 3239).

- Eisenhaber F, Persson B, Argos P. Protein structure prediction: recognition of primary, secondary, and tertiary structural features from amino acid sequence. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1995;30(1):1-94. doi: 10.3109/10409239509085139. PMID: 7587278