Cracking the Ammonia Code: Balancing Global Food Security and Environmental Sustainability

Ammonia, a simple yet critical molecule, feeds half of the world’s population, thanks to the Haber-Bosch process. However, its energy-intensive production and environmental impacts raise urgent questions about sustainability. The rising demand for ammonia-based fertilisers fuels a global environmental dilemma, as nitrogen runoff creates dead zones and contributes to climate change. A promising solution lies in “green ammonia,” which could revolutionise the industry by replacing fossil fuels with renewable energy. While the costs remain high, breakthroughs in catalysts and new methods could unlock a sustainable future for ammonia production.

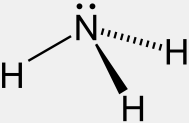

Ammonia, an invisible gas, sounds deceptive. It consists of one nitrogen atom bound to three hydrogen atoms in a trigonal pyramidal shape. That’s it! The Nitrogen we breathe daily, which makes up 78% of Earth’s atmosphere, is locked in a powerful triple bond (N≡N). The real challenge lies in breaking and activating this bond.

It feels like one of those unrequited scientific loves, with no perpetual remedy! From the vast cornfields of the Midwest to the rice paddies of Asia, this simple compound is essential for sustaining nearly half of the global population. Its silent yet immense contribution to global energy dynamics is paradoxical, demanding an urgent verdict in favour of nature. Yet, it remains the linchpin in the production of all nitrogenous fertilisers, without which global food production would collapse. Over 150 million metric tons of ammonia are produced each year—80% of which is used globally to make crops grow faster, healthier, and more robust, ultimately feeding the world.

The Haber-Bosch Process: A Century of Innovation and Beyond

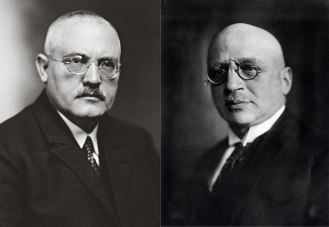

In the early 20th century, two German scientists—Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch—cracked the code and devised a method for the mass production of ammonia. Their process, known as the Haber-Bosch process, made history and transformed the world. Initially, it relied on a combination of iron-based (Fe) catalysts, nitrogen (N₂) from the air, and hydrogen (H₂) typically sourced from natural gas. These elements were subjected to extreme conditions: heat up to 400-500°C and pressure between 200-400 atmospheres. Later, a modified version of the process, incorporating a Palladium (Pd) promoter, was introduced, and was deemed promising for maximising ammonia output while minimising energy input.

On paper, the reaction seems straightforward:

However, this simple equation masks the massive energy cost involved. The Haber-Bosch process is an energy-intensive behemoth, consuming around 1-2% of the world’s total energy. This is because breaking the N≡N triple bond requires vast amounts of energy. Specifically, natural gas (methane, CH₄) is reacted with steam (H₂O) in the presence of a catalyst to produce hydrogen (H₂) and carbon monoxide (CO), followed by the water-gas shift reaction to convert CO to carbon dioxide (CO₂) and produce additional hydrogen. Hydrogen and nitrogen gases are then combined under high pressure and high temperature to form ammonia (NH₃). This entire process generates an estimated 420 million tons of CO₂ annually, making the fertiliser industry a key perpetrator of global greenhouse gas emissions.

Fig 2. Carl Bosch (left) and Fritz Haber (right). They made groundbreaking contributions to chemistry by developing the Haber-Bosch process, which synthesises ammonia from nitrogen and hydrogen gases under high pressure and temperature. Fritz Haber discovered the reaction in the early 20th century, creating a way to convert atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia. Bosch’s innovations enabled mass production of ammonia, leading to more abundant fertilizer supplies.

Fig 2. Carl Bosch (left) and Fritz Haber (right). They made groundbreaking contributions to chemistry by developing the Haber-Bosch process, which synthesises ammonia from nitrogen and hydrogen gases under high pressure and temperature. Fritz Haber discovered the reaction in the early 20th century, creating a way to convert atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia. Bosch’s innovations enabled mass production of ammonia, leading to more abundant fertilizer supplies.

The Ammoniated-Environmental Reckoning: Beyond CO₂ and towards sustainability

The environmental impact of ammonia production stretches far beyond its carbon footprint. Misusing ammonia-based fertilisers leads to eutrophication, while excess nitrogen runoff contaminates water bodies, triggering algal blooms. This effect depletes oxygen levels and creates dead zones—such as the one in the Gulf of Mexico. As the global population rapidly escalates, the demand for ammonia in agriculture grows exponentially, establishing a critical environmental reckoning. These ecological disruptions highlight the urgent need to address the hidden environmental costs and make us wonder whether true sustainability would require immediate action on these broader consequences.

Our reliance on ammonia, once hailed as a breakthrough, now presents a paradox: how do we sustain its benefits without compromising the environment? Reflecting on this, environmental scientist Dr. Sarah Patel states, “The challenge isn’t just making ammonia sustainable at the production stage. We also need to rethink how we use it to minimise its downstream environmental impact.”

Fig 3. Ammonia (NH₃) is a simple molecule composed of one

nitrogen atom and three hydrogen atoms, arranged in a trigonal pyramidal shape. This geometry is due to the lone pair of electrons on the nitrogen atom, which repels the hydrogen atoms downward, creating an angle of about 107.8° between the hydrogen atoms. The nitrogen atom has a partial negative charge, while the hydrogens have a partial positive charge, making ammonia a polar molecule.

Fig 3. Ammonia (NH₃) is a simple molecule composed of one

nitrogen atom and three hydrogen atoms, arranged in a trigonal pyramidal shape. This geometry is due to the lone pair of electrons on the nitrogen atom, which repels the hydrogen atoms downward, creating an angle of about 107.8° between the hydrogen atoms. The nitrogen atom has a partial negative charge, while the hydrogens have a partial positive charge, making ammonia a polar molecule.

“Green” Ammonia: A Vision for the Future?

So, is there a solution to this issue? Yes! The answer lies in the concept of green ammonia, a futuristic vision that offers hope to the entire scientific community. It seeks to replace fossil fuels with renewable energy sources in hydrogen production. Instead of deriving hydrogen from natural gas, water electrolysis can be used to produce hydrogen using solar, wind, or hydroelectric power, leading to zero carbon emissions from the hydrogen production stage.

As always, the catch is the cost. Today, producing green ammonia is significantly more expensive than the traditional method. But as renewable energy becomes more affordable, scientists hope that green ammonia will eventually compete with its fossil-fueled counterpart. In this regard, Dr. Maya Jensen, a sustainable chemistry expert, notes, “If we can crack the cost barrier, green ammonia could be the solution to feeding the world without cooking the planet.”

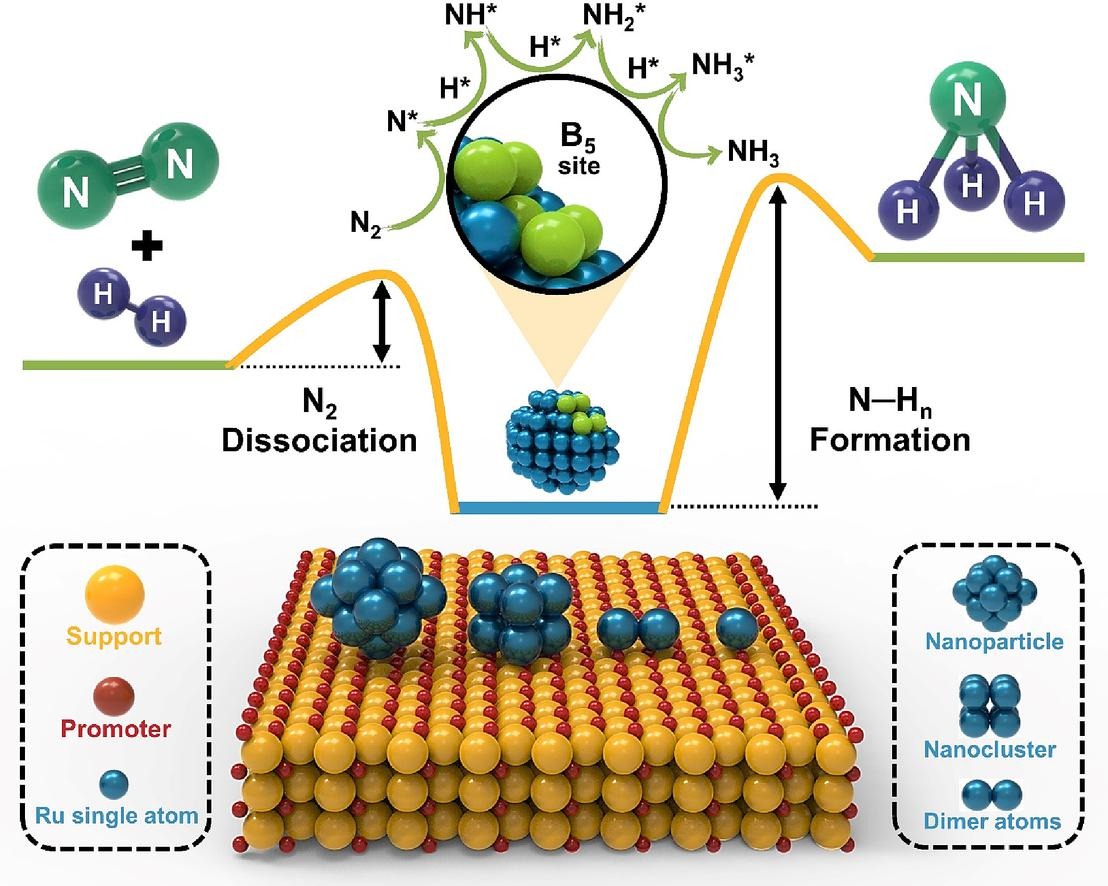

The Quest for Smarter Catalysts and Innovative Methods in Ammonia Production The bottleneck in sustainable ammonia production is discovering an effective catalyst for the nitrogen-hydrogen reaction. Traditional iron (Fe)-based catalysts require extreme heat and pressure, which leads to high energy demands in the Haber-Bosch process. Researchers are now exploring new materials, from ruthenium (Ru)-based catalysts to exotic compounds, in hopes of optimising temperature and pressure requirements to reduce energy costs.

There has been a recent surge in innovative strategies that aim to revolutionise ammonia (NH₃) synthesis by activating molecular nitrogen (N₂) under ambient conditions. Pioneering research is being carried out along diverse approaches—from photochemical and electrochemical methods to advanced metallic and organometallic pathways.

Electrochemical methods, powered by renewable electricity, aim to reduce nitrogen to ammonia in low-energy setups, although current systems struggle with low yields and high energy demands. Meanwhile, photocatalysis harnesses sunlight to drive ammonia synthesis, with hopes of creating a solar-powered process in the future. Other studies have demonstrated the potential of organometallic compounds, metallic clusters, frustrated Lewis pairs (FLPs), and carbenes to activate N₂ and facilitate NH₃ fixation.

These cutting-edge discoveries and novel inventions bring hope for transforming the traditional Haber-Bosch process. Yet, despite their promising results in the lab, upscaling these methods to industrial applications remains a formidable challenge.

Fig 5. New advancements in ammonia synthesis include the use of single-atom ruthenium (Ru) catalysts, which significantly increase catalytic efficiency by maximising active site exposure and enhancing structural sensitivity. These Ru catalysts enable efficient ammonia production through thermocatalysis, photocatalysis, and electrocatalysis while reducing reaction energy requirements.

Fig 5. New advancements in ammonia synthesis include the use of single-atom ruthenium (Ru) catalysts, which significantly increase catalytic efficiency by maximising active site exposure and enhancing structural sensitivity. These Ru catalysts enable efficient ammonia production through thermocatalysis, photocatalysis, and electrocatalysis while reducing reaction energy requirements.

Where We Stand

Ammonia’s journey is a unique one—marked by scientific promise and significant challenges. It has sustained billions and now stands at a critical juncture, with scientists working to secure its future in a greener, more sustainable way. Whether through advanced catalysis, renewable hydrogen, or innovative synthesis methods, ammonia’s future promises to be one of the most pivotal developments in modern chemistry.

Efforts to develop green ammonia and cutting-edge catalytic technologies are transforming the ammonia-production process into a more sustainable endeavour. As Dr. Patel notes, “The future of ammonia will help decide the future of our planet. With stakes this high, it’s not just about chemistry—it’s about survival.” The story of ammonia extends beyond chemistry, reflecting past and present constraints while offering hope for sustainability and innovation in one of the world’s most energy-intensive industries.

References

- Haber, F., & Bosch, C. (1913). The synthesis of ammonia from its elements. Zeitschrift für Elektrochemie und angewandte physikalische Chemie, 19, 53-56.

- Appl, M. (1999). Ammonia: Principles and Industrial Practice. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH.

- Smil, V. (2001). Enriching the Earth: Fritz Haber, Carl Bosch, and the Transformation of World Food Production. MIT Press.

- Schlögl, R. (2015). Ammonia Synthesis: The Most Important Scientific and Technological Advance of the 20th Century? Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 54(11), 3465-3491.

- Patel, M. R. (2022). Advancements in Catalytic Processes for Ammonia Synthesis: Challenges and Innovations. Journal of Catalysis, 410, 108-125.

- Chen, J. G., Crooks, R. M., Kim, K. S., & Sun, Y. (2021). Renewable Energy and Sustainable Ammonia Production. Nature Reviews Chemistry, 5, 567-582.

- Rees, N. V., & Compton, R. G. (2011). Sustainable Approaches to Ammonia Synthesis. Energy & Environmental Science, 4(4), 1255-1260.

- Rouwenhorst, K. H., van der Ham, C. J. M., Mul, G., & Kersten, S. R. A. (2019). Power-to-Ammonia: An Overview of the Technical and Economic Feasibility. Journal of Energy Storage, 26, 100836.

- Ribeiro, F. H., & Somorjai, G. A. (2020). The Role of Catalysis in Sustainable Ammonia Production. Chemical Reviews, 120(15), 7917-7990.

- Giddey, S., Badwal, S. P. S., & Munnings, C. (2013). Ammonia Production: Recent Advances in Electrochemical Synthesis and Catalysis. Frontiers in Energy Research, 1, 19.

- Sen, S.; Bag, A.; & Pal, S. (2023) Activation and Conversion of Molecular Nitrogen to the Precursor of Ammonia on Silicon Substituted Cyclo[18]Carbon: A DFT Design, ChemPhysChem 24, e202200627.

- Sen, S.; Bag, A.; & Pal, S. (2024) Mechanistic Inquisition on the Reduction of C17Si-(NH2)2 to NH3: A DFT Study, ChemPhysChem, e202300723.