Prof. Somnath Dasgupta: Four decades of studying the earth

Interview

Abhinav Thakur

In a career spanning over more than 40 years and still going strong, Prof Somnath Dasgupta takes us on an unforgettable journey about how he stepped into the field of Earth Sciences and eventually into academia. He shares anecdotes from his many adventures around the world and also shares his experiences as one of the first faculty members at IISER Kolkata.

Tweet

1. You took up Geosciences as major during your undergraduate days. Was it a random choice or was there more to that decision? What kind of a seeker, according to you, should step into this avenue of science?

I graduated in 1968 from a modest high school located in the suburbs of Kolkata and was not exposed to the company of real academic stars of those days. My reply needs to be viewed in this context (also that there was no internet). At that time, all science students aimed at higher studies in science subjects, and not engineering. I qualified for engineering, which I discarded promptly. I had initially enrolled for a Chemistry major, but did not join.

When I was in Std VIII, I went on a vacation with my parents to Darjeeling, where we happened to stay at the same hotel with two other families. Both were headed by two professors from the Department of Geological Sciences, Jadavpur University, and I learned something about the subject from them. What appealed to me especially was fieldwork- chances to visit many remote and beautiful places and study rocks, minerals, and fossils to understand how the Earth works. So I ditched Chemistry for Geology.

There was another less important factor. A senior student from my school went to study Geology, and I heard some stories from him too. I knew very little, but I was intrigued by the challenge. So my decision wasn’t completely random, but chance events did have a role to play.

I chose to study at Jadavpur University. It will not be out of place to mention here that my excitement with Earth Sciences in the initial period was due to two fortuitous events - Plate Tectonics, which came up in 1970 when I was a second-year undergraduate and the Apollo mission to the Moon in 1969 and results of a study of the samples from the Moon. Both opened up a new vista in Earth Sciences.

Now, who would seek to study this subject? Basically, someone who is intrigued by natural processes, physical, chemical, and biological, viewed in totality and wants to learn about them. Someone, who cares for the environment or climate change or disasters or even economic growth of the nation, and wants to learn about them. In short, anyone who wishes to see a sustainable planet. In my opinion, it is this 360 degree vision that makes Earth Sciences a challenging discipline. In advanced stages of career, one may wish to specialize in any one of the natural processes (physical, chemical or biological) of choice.

2. During the early days of your research career, you spent considerable time working for the Geological Survey of India. What made you choose academia over a well-reputed government scientific agency?

Taken in 1990 with one batch of students from Jadavpur University

Taken in 1990 with one batch of students from Jadavpur University

I completed the work component of my Ph.D. before joining the Geological Survey of India (GSI). There was simply no job opportunity in academia at that time, and I could not wait long due to family constraints. So I appeared for UPSC, got selected and joined GSI. I was greatly benefited by the training and unparalleled exposure I received there, particularly learning about the geology of practically every part of our country. I, however, nurtured my academic ambition all through, and once I got an opportunity, I joined Jadavpur University. The switchover, which came with a significant reduction in salary, was primarily driven by two factors: my ardent desire to teach and my wish to pursue a research career that is decided by my choice only, not by any bureaucracy. I strongly believe that these reasons are common to all, who choose a teaching-cum-research career. I never considered a research position in different national scientific laboratories because of my inclination to teach, particularly to undergraduate students.

3. To an uninitiated, how would you explain your area of expertise and its relevance to the world around us?

Over the last 40 years, I have moved quite a lot in terms of research interest - , working on several branches of Earth Sciences, with the central theme of application of chemical principles like thermodynamics and kinetics, in a solid state system - the Earth. In these years I have worked on concentration of copper and manganese to form large natural deposits, the geological configuration of the Indian subcontinent through several cycles of assembly and dispersion, mountain building processes - particularly the Himalayas, quantification of compositional change in sea-water over the geological time-scale alongside many other natural phenomena. Results from all these investigations are used to understand the processes that shaped the evolution of the Earth and our habitat not only in deep time, but also in the recent past and, therefore, are directly relevant to the society at large. Past trends can be extended to the near future, hence these results can be used to predict how the economic resources will evolve and how can we sustain these, how the Earth’s climate system is controlled by the movement of large landmass chunks below the earth's surface - plate tectonics, , how can we mitigate natural disasters and others. These findings have revolutionized concepts and phenomena that control our future to a large extent.

4. You were one of the earliest faculty who joined the newly formed IISER Kolkata's Department of Earth Sciences in 2007. Many alumni of the first batch are now successfully working in various academic and industrial positions. How do you think the institute has grown from the seed that you had sown 13 years ago to the present? Where do you see the department in say, next 10 years?

Prof. Somnath Dasgupta with the students of the first batch of Earth Science Major in 2010

Prof. Somnath Dasgupta with the students of the first batch of Earth Science Major in 2010

When I heard about the plan to establish IISERs, I started to nurture a hope that Earth Sciences will be included as one of the major subjects. I was supported by many senior scientists from other branches, and in a meeting held in 2005, it was decided to start experimenting with an introductory course in Earth Sciences at IISER Kolkata. So, after IISER Kolkata was established in 2006, I moved over as the first faculty in this discipline. For the first two years, I just taught the introductory course. Subsequently, we started offering a major from 2009, as other colleagues joined. But the Department of Earth Sciences faced a tough time as the other colleagues who had joined eventually left and I remained as the sole faculty member for about a year and we managed with the help of a few visiting faculty. I received full support from the then Director to develop the Department afresh. The present faculty members joined subsequently. The first batch of ES majors graduated in 2012, and I feel very happy to see them well established in life in their chosen fields.

From the beginning we had planned to develop the department in a non-traditional way to provide multidisciplinary training interfacing with all other branches. As you can see, faculty members in this department come from a wide variety of backgrounds. It is not for me to say how far we have succeeded. Students graduating over the last 8 years should be the judge. We have now reached a mature stage with the right combination of traditional and non-traditional courses. Since the number of students has increased over time, we have to consider various career options for them, not just in research.

We need feedback from students and the department would like some concrete points from the outgoing batch. The only suggestion that I have for the students is that they should compete more seriously in national level examinations, such as NET or GATE. Even if you want to go abroad to pursue higher studies, why don't you just appear to check where you stand in the national level? Any success is a morale booster. We have many sophisticated instruments and I would like to see ALL the students get properly trained. This will be an important addition to their resume as well.

With my departure, it is a youthful Department, so I have great hopes. But I have also seen the rise and fall of great Departments / Institutions in the last 40 years, so I shall keep my fingers crossed, but with the highest expectations. I shall urge the Department to keep in constant touch with alumni and seek their help and suggestions for improvement.

5. While unravelling the mysteries of the earth, you must have travelled a lot around the world for field investigations. Can you share some stories from your most memorable expeditions?

This is the most difficult part because of space constraints. I have done extensive field studies in all the continents, other than Antarctica. I got an opportunity to visit Antarctica quite early in my career but declined because at that particular stage I could not afford a 6-month visit. I shall mention about only three expeditions under very different and unique settings- ocean, mountain, and desert.

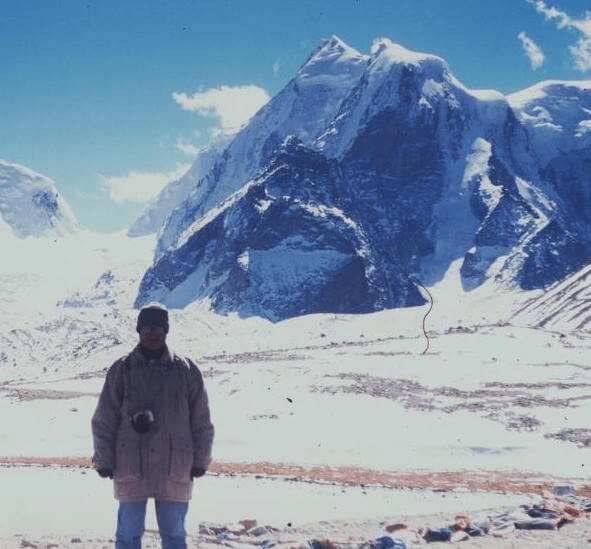

At a glacier in Sikkim Himalaya at an altitude of 6100 metres

At a glacier in Sikkim Himalaya at an altitude of 6100 metres

I was part of an Indian oceanographic team in June-July 1985, when we travelled from Goa to Mauritius and back. It took us 48 days, but it was a huge experience for me to learn the technique of sampling deep sea rocks from a depth of 5 km in the equatorial Indian ocean, study them, and even analyze them on board. From there, we also monitored the progress of the monsoon, sent weather balloons and analyzed the data acquired, all while sailing through the mesmerizing Indian ocean. Life on the ship was quite memorable and it taught me about things I did not know anything about. When a ship crosses the equator, it stops there for a day and all of us participated in a funny ritual to please King Neptune- it was kind of ragging. With the help of an echo sounder equipment, we mapped the ocean floor, and it was amazing to see the suboceanic topography from the images. One interesting, but frightening, experience was that I was hit by a flying fish from behind while working on the deck.

The Himalayas always fascinated me not only for its geological significance but also for the majestic beauty. I have visited the entire stretch from Ladakh to Arunachal Pradesh, went up to an altitude of 6000 meters, spent months in alpine tents and in army camps, mapped unknown territories, looked at the contact between the Indian and Eurasian plate and a part of the Tethyan ocean floor that has been thrust over the Eurasian plate and saw how melting of glaciers produce the big rivers. This is only a part of the list. Above all, I enjoyed the magnificent scenery, which only a geologist or a mountaineer can see.

Lastly, the desert. I traveled across the Kalahari Desert in 1993 over a distance of 2000 kilometers and studied desert landforms and the largest manganese deposits of the world. Nights in the desert are so beautiful and I have not seen so many stars ever again. Unfortunately, we did not have telescopes for closer inspection. The experience of tolerating a temperature difference of 44 degrees Celsius between the day and the night was quite difficult. But the limitless sandy and gritty soil and the savannah with practically no life form, other than scorpions (we did not come across any of the famous big cats, foxes or bears) and the strong winds are all scary, but mind-boggling at the same time.

Standing on the ship in the middle of the Indian ocean or at the top of a peak in Lahaul-Spiti or amidst the sandy soil of the Kalahari and gazing at the starlit sky, I always realized how insignificant I am!

6. You were awarded the Teachers Award in 2014 by the Indian National Science Academy. In your career as a professor spanning over four decades, you have taught generations of students in classrooms, laboratories and the field. What are the challenges in earth science pedagogy, which involves an interplay of these three places of learning? Which, amongst these three, is your favourite part?

My motivation in teaching has always been the queries and challenges posed by the students and research scholars. All the three aspects (classroom teaching, laboratory training and field work) are important and one compliments the other. Field work is vital in any sub-discipline of Earth Sciences, basically because it is a Natural Science. These days students can do lots of “virtual” fieldwork through the internet, but this can never substitute actual field observations. For 30 years I have taken student batches to the field and have seen (in addition to scientific knowledge, which is the most important one) how that positively affected the development of their social skills. Even those carrying out absolutely theoretical research need questions supplied by natural phenomena. Therefore, the role of field work cannot be underplayed.

Laboratory investigations or training are primarily aimed at solving questions that nature poses. While students should be trained in instrumentation, they should not be held captive there. Instruments are there to solve your research questions quantitatively, but your mind dictates what should be the research question. I have seen many cases where scientists became slaves to instruments, which is a huge problem. One can take the route of theoretical modelling or computation to solve questions, avoiding analytical instruments, but one has to define a proper question first. Since nature offers us many unsolved mysteries, study of nature is the easiest way to formulate a question.

As for classroom teaching, there is no substitute.

It is extremely unfortunate that for the first time in my career, I am compelled to take the route of virtual teaching, due to the ongoing pandemic. It does not have the same excitement or sense of fulfilment. By definition, Earth Sciences is multidisciplinary as we travel from the space to the core of the earth, via the surface of the earth where we deal with life forms, and we know that every component of Earth System Science interacts with each other. Therefore, we need the right combination of field work (where applicable), laboratory investigations and theoretical analysis to arrive at a conclusion. Being a field geologist, my favourite is clearly defined. But I am aware that this is just one side of the coin and I need other avenues to solve questions.

7. Many renowned academicians have written extensively about mainstream scientists having poor opinions of geologists as scientists and geology as a ‘real science’. For example, Indian geologist KS Valdiya wrote in one of his articles, “The geologists, who toil hard for finding minerals for scientific research and industrial development, sources of water for multifarious needs, make sustained efforts to make India self-sufficient in energy and help select appropriate sites for dams, power plants, alignments of roads and tunnels, suggesting ways of overcoming problems of stability and natural hazards, go ‘unwept, unhonoured and unsung’”. What are your views on this and do you think that geologists are not celebrated as much as they should be like other sciences?

While completely agreeing to this view (barring the last few words), I do not think that as an Earth Scientist, we should have an inferiority complex, and neither was I ever discriminated against. Any sensible person would accept the importance of this discipline on their own right without going into unnecessary comparison. It will be hilarious, for example, to debate whether finding water is more important than discovering medicines or vice versa. There is ample evidence that Earth Scientists have been equally honoured as others. True that we do not have a Nobel Prize, like Mathematics. But nobody can deny the societal relevance of Earth Sciences and everybody acknowledges our efforts to make this planet habitable for generations to come. If the world wishes to meet the United Nations mandated Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) by 2030, there is simply no alternative.

This interview was conducted by Abhinav for Cogito137.

Abhinav is a final year BS-MS student in the Department of Earth Sciences at IISER Kolkata. He is currently working on Precambrian volcanism in Eastern India for his master's thesis with the Crustal Evolution Group at IISER Kolkata. Outside the lab, he is a mountaineering enthusiast and enjoys doing guitar improvisations on the blues scale.

signup with your email to get the latest articles instantly